#26 - CSIS Wargame Analysis

战争游戏 - Zhan4Zheng1 You2Xi4 - Wargame

Executive Summary

CSIS is a US think tank that released an unclassified report on their recent series of war games. The report can be found here.

During these war games, CSIS identified four critical conditions for success in defeating a Chinese invasion:

1. Taiwanese forces must have the will to fight.

Why? If Taiwanese ground forces do not significantly slow down the Chinese advance, it does not give the US enough time to destroy the Chinese amphibious fleet and any ports or airports the Chinese have captured on Taiwan. It is the destruction of these assets that leads to Allied victory.

2. Ukraine-style assistance does not work for Taiwan.

Why? The intense Chinese air, sea, and missile blockade of Taiwan makes it impossible to move supplies onto the island for weeks.

3. The US must be able to fight from Japanese bases.

Why? Without Japanese air bases, US platforms are too far away from the fight to be efficient.

4. The US must strike Chinese fleet forces (in particular amphibious ships) rapidly and effectively.

Why? If the Chinese amphibious fleet is able to constantly land fresh troops, it is only a matter of time until Taiwan is overwhelmed (possibly less than 10 weeks).

How Did the Wargame Work?

CSIS chose to model a Chinese invasion of Taiwan in the year 2026. CSIS then developed a rules set and game board and had multiple teams of experts (from both within and outside of government) play against each other as China, Taiwan, Japan, and the US. Each team issued orders to cover a single turn consisting of 3.5 days of game time. Most games lasted 3 to 4 weeks of total game time. When forces engaged in battle, CSIS utilized the rules set to adjudicate the outcome. CSIS constructed these rules by drawing on the method of history and the method of Pk.

Method of History

This method “models the results of future military operations by making analogies with past military operations at the appropriate level of analysis.” For example, the rate at which PLA amphibious forces are able to offload tonnage in the game was derived from real world late-WWII US amphibious tonnage offload rates. By harvesting historical military data, CSIS is able to rely on real world operations instead of exclusively theoretical data.

Method of Pk

This method “models the results of military operations by assigning probabilities and values to…weapons systems[.]” Pk means probability of kill, and represents the percentage chance of a successful attack. When a missile was fired in the game, CSIS assigned a percentage of success to the attack. To calculate Pk for various weapons, the CSIS team utilized available operational and testing data.

To understand how these methods can come together to create rules to adjudicate the outcome of tactical actions, please read the below insets directly from the CSIS report on the topic of anti-ship missile interception.

By utilizing this rules set, CSIS was able to rely on clear cut adjudication rather than the personal judgment of experts acting as referees of the wargame.

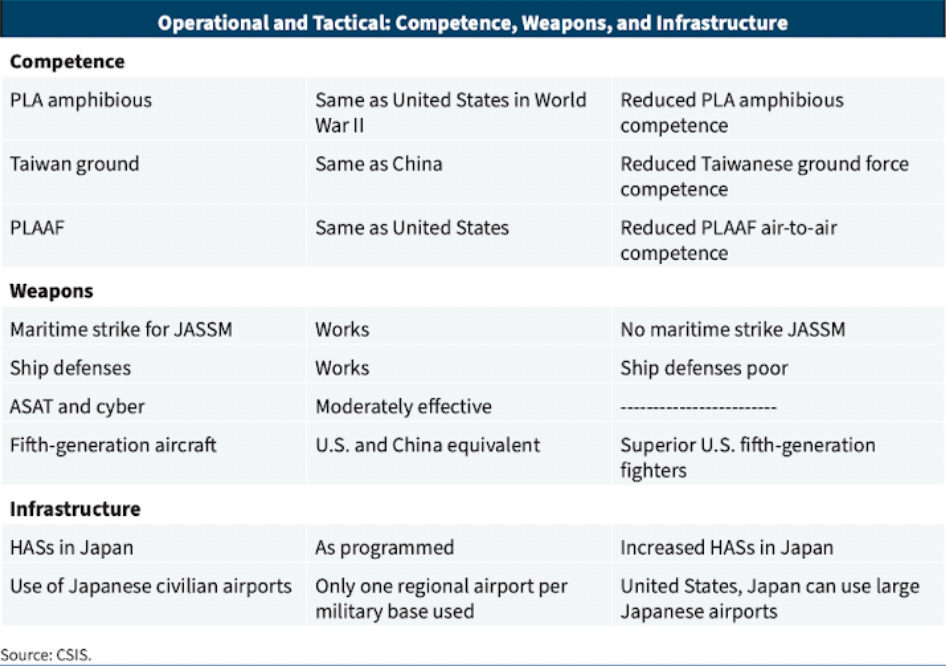

To create an even more robust final assessment, CSIS ran the wargame 24 times. Within this set of iterations, the same base case (scenario) was run 3 times, while 21 iterations were run with different assumptions. The base case assumptions are listed below in the middle column, with excursion assumptions listed in the right hand column.

1. A couple of these assumptions bear discussing. The first is that PLA amphibious forces are as competent as the US in late WWII (44-45). During these years, US forces were quite adept at amphibious landings, reaching a high peak level of capability resting on a foundation of practice in the interwar years along with hard won Allied experience in operations Chariot, Jubilee, Ironclad, Torch, Agreement, Husky, Baytown, Slapstick, Avalanche, Landcrab, Watchtower, Cleanslate, Drake, Cherry Blossom/Cartwheel, Chronicle/Cartwheel, Toenails/Cartwheel, Director/Cartwheel, and Galvanic.

In fact, by the end of 1943, the Allies were beginning to peak as the most experienced and capable amphibious coalition in history. The above operations launched amphibious assaults and landings of variable size and success across Europe, the Mediterranean, Africa, Alaska, and throughout the Pacific. This massive amount of experience was then digested, disseminated, and integrated into the largest amphibious operations in history, the US/Allied amphibious assaults of Operation Overlord/Normandy and the even larger landing force of Operation Iceberg/Okinawa, among other amphibious ops in ‘44/’45. It is almost certain that current-day PLA amphibious forces would not display such operational dexterity from a cold start.

The CSIS team acknowledges this point on page 103 of the report. To counterbalance in CSIS’s favor, modern technology will likely help to increase throughput of tonnage. Also, in this game, Chinese civilian vessels were limited to port use only. This will likely not be the case, since Chinese civilian boats have supported every historical PLA invasion. A massive (tens of thousands) civilian supply convoy could help increase PLA amphibious tonnage throughput.

2. The second interesting assumption is that US, Chinese, Taiwanese, and Japanese forces have equivalent levels of operational competence. Specifically, China’s People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and the US Air Force are given the same level of competency, as well as equivalency in quality of 5th generation airframes (US: F22 and F35, PRC: J20).

This would be quite a surprise, since it is almost certain that PLA forces are not as competent as their US counterparts, both today and historically during the Korean War. To be fair, Taiwan forces may be less competent than Chinese forces. CSIS assumes that Taiwan resists vigorously, playing all of its capabilities instead of collapsing quickly. There are many possible configurations of this variable, which is why the CSIS team may have assigned every force the same competence, to decrease complexity.

3. CSIS also assumes a relatively quick Chinese military mobilization of thirty days before D-day. For an operation as large as the invasion of Taiwan, 30 days is likely insufficient. Russia built up troops along the Ukrainian border for months before launching the invasion and never had to contend with crossing a major body of water.

On the flip side, the US and Taiwan are given unambiguous warning at D minus 14. The line needed to be drawn somewhere, but this could vary significantly, with serious implications to Washington’s military strategy and the defense of Taiwan.

4. The final assumption worth highlighting is that the global US munition inventory is available to Pacific forces. To their credit, CSIS does include a decrement to US strategic airlift dedicated to munition distribution. However, the ability to move munitions to all the right places at all the right times would be a nightmare-inducing operation. It is not clear if US logistics forces have the capacity to sustain the US operations conducted during these iterations.

Base Case Scenarios

CSIS ran three separate iterations of the base case scenario (middle column assumptions in the graph above). In two iterations, China was decisively defeated, with PLA forces ashore unable to capture a major city and out of supplies within 10 days. In one iteration, PLA forces landed in the south and captured the port of Tainan. US air strikes prevented Tainan’s use for the majority of the time, leaving the Chinese position indefensible by D+21. In all cases, at least 90% of the Chinese amphibious fleet was destroyed which severely curtailed logistics support to the Chinese landing force.

In base case iterations (each iteration lasting several weeks of game time), China was generally able to land a total of 37 battalions onto Taiwan, with an average of 30 battalions (30,000 troops) surviving at the end of gameplay. This force was able to seize 7% of Taiwan's territory by game end.

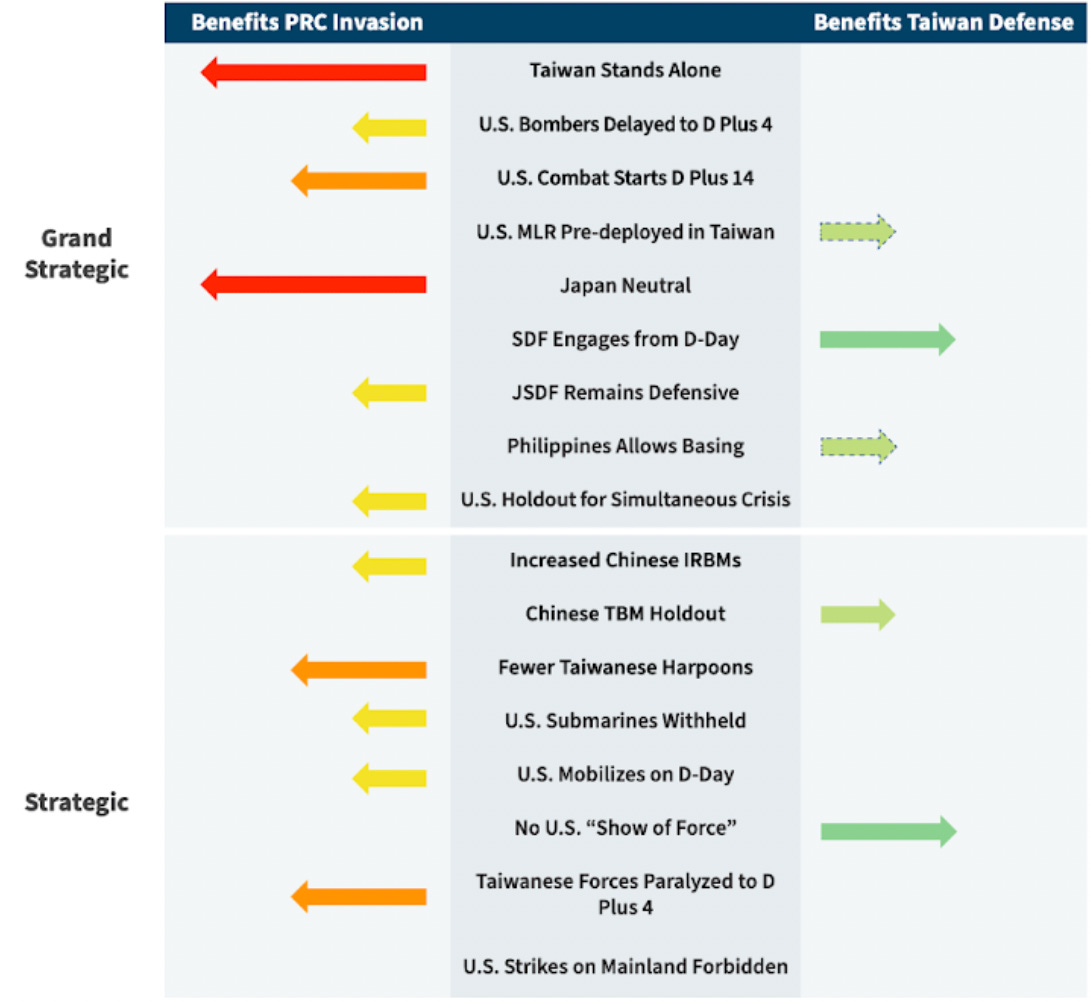

Pessimistic Scenarios

CSIS also explored 19 iterations of the game with different assumptions more favorable to China. In all of these pessimistic scenarios, versions of the AGM-158 (check Vermilion’s Instagram for a deep dive into the AGM-158 missile system) that were not the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) were unable to target moving naval vessels. Without the LRASMs, the US was forced to lean heavily on fighter aircraft employing the shorter range Joint Strike Missile (JSM) and Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW). This resulted in higher US aircraft losses. Ironically, 5th gen fighters were more useful in these close range knife-fight battles because of their stealthy characteristics.

While the operational results of these 19 iterations were much better for China than the base case, none resulted in a Chinese occupation of Taipei nor the seizure of more than 25% of the island within the several week timeframe. These iterations mostly resulted in stalemate, with only 3 cases resulting in a stalemate favoring China.

In these protracted stalemate scenarios, the critical capability seemed to be resupply of ground forces fighting on both sides. This meant that the Allies were required to convoy supplies to the island under air and missile attack while China was required to continuously repair port and airfield infrastructure while under air and missile attack in kind.

In pessimistic scenarios, the PLA was able to land an average of 60 battalions. At the end of the game, PLA forces averaged 43 battalions (43,000 troops) remaining on island during these iterations, controlling an average of 17% of Taiwan’s territory. Losses from ground combat averaged 17,000 PLA casualties and 22,000 Taiwanese. These were much higher losses than the other iterations because more Chinese units got ashore and each unit was able to fight more intensively.

Optimistic Scenarios

Two iterations were run with more optimistic/US friendly assumptions. Some of these assumptions included less competent Chinese amphibious forces, superior US pilot competence, reduced effectiveness of ship defenses for all combatants, more resilient US force posture, and others. Both optimistic iterations produced decisive Chinese defeats.

Taiwan Stands Alone

CSIS conducted a single iteration where Taiwan fought China without any outside material assistance. This iteration resulted in a decisive Chinese victory, with PLA armor units occupying the president’s palace in Taipei after 10 weeks of fighting.

In this iteration, Taiwan’s commander flowed forces to meet the Chinese attack while simultaneously defending successive river and ridge lines, running from south to north. China required heavy armor (main battle tanks), artillery, and engineer support to dislodge these defensive lines. Transporting these heavy forces across the strait required substantial time.

When Taiwanese defenses were dug into foothills or steep mountains, the Chinese commander relied on light infantry to turn the defender’s flank in successful attempts to pressure Taiwanese retrogrades to the next river or ridge line.

The PLA landed a total of 230 battalions on Taiwan and the amphibious fleet remained in operation throughout, regardless of Taiwanese shore-based anti-ship cruise missiles. 65 PLA battalions were rendered combat ineffective, with 165 surviving through the capture of Taipei.

Reflections from Numerous Playthroughs - What Were the Critical Variables?

1. If China is able to secure ports and airfields while keeping them repaired and operational, Beijing eventually wins. If it cannot, the invasion force melts away. Once China captures an operational port or airfield, it can begin utilizing civilian vessels and aircraft to supply the invasion, easing demands on the limited capacity of the amphibious fleet.

In turn, China’s success or failure also hinges on its ability to defend the amphibious fleet long enough to achieve objectives ashore. Submarines were very successful in engaging the amphibious fleet but could only inflict a moderate amount of damage due to a limited number of on-board torpedoes and long reload times (heading back to port). Bombers and fighters with high carrying capacity and rapid rearm times proved the most potent threat to Chinese amphibious shipping.

The US AGM-158C LRASM may have been the most effective single weapon in the game. Mass launches of LRASM devastated Chinese surface forces, and the 2026 US global inventory of LRASMs (about 450 missiles) was expended within 7 days. After the LRASM inventory was depleted, the US reached for other versions of the AGM-158 that CSIS assumed in the base case were still able to target moving naval vessels.

In iterations where US JASSM or JASSM-ER missiles cannot hit moving vessels, the US has a far more difficult time and takes far more casualties when intervening. The ability to deliver standoff strikes en masse was one of the single biggest variables identified.

It is very clear that the US requires multiple types of precision long-range standoff missiles. One missile type should target ships, another infrastructure, a third aircraft, and a final one for support to ground forces. The LRASM likely works well enough to destroy Chinese surface vessels, though the number of munitions was clearly insufficient.

The JASSM-ER worked somewhat well in targeting infrastructure because it carries a unitary warhead, meaning it contains one bulk fill of explosives with no other exotic effects. However, the JASSM-ER was meant to destroy platforms (sea vessels/air defense), not necessarily infrastructure. There are better ways to destroy and deny infrastructure targets with submunitions or special warheads that create better craters in concrete. A new missile must be developed specifically for this purpose.

The US also needs a way to clear the skies of enemy aircraft. By utilizing deep airstrikes, the Chinese were able to significantly delay Taiwanese ground forces from joining the fight, which was very effective in increasing China’s gains. The LRASM and JASSM-ER aren’t the right tools for this job because they are very heavy with quite large warheads, overkill for taking down thin-skinned airframes. Current US air-to-air missiles have a much shorter range than their Chinese counterparts, something that should immediately be remedied.

Since the ground fighting on Taiwan is ultimately the critical centerpiece, it makes little sense for the US to isolate itself and focus only on enablers like the amphibious fleet. A standoff ground support munition must be invented. It will not be a unitary warhead, but some combination of high explosive fragmentation and/or tank hunting submunitions. The US already has this technology and must simply package it in a standoff format.

The real challenge will be developing the people side of the system, where a mandarin speaking Taiwanese ground force officer requests fire support from an english speaking air operations center or pilot loaded for bear with missiles ready to fire. At current rates of unhurried bureaucratic entropy, it will take years to develop the training and integration to deploy this critical capability.

2. When Chinese airborne forces attempted to seize airfields, they generally failed due to the light weight nature of these forces. When airborne were used to isolate beach landing zones right before landing they were much more successful and generally survived to link up with the landing force.

As CSIS points out, the failed Russian airborne attack on Hostomel in 2022 displays the risks of such operations. Additionally, during Operation Overlord / the Normandy Invasion, Airborne forces were also generally dropped behind beach landing zones with success.

3. During the initial stages of conflict, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) enjoys air superiority over Taiwan, allowing the Chinese to significantly obstruct the movement of Taiwanese ground forces to the battle area. China’s ability to advance off the beaches landing zones and establish lodgment depended heavily on airpower. Direct close air support was required but far more important was Chinese air interdiction of Taiwan forces moving behind the lines positioning themselves for counter attack.

While shooting down Chinese aircraft from afar is one solution (mentioned above), another is death from below. The US and Taiwan can’t afford to allow China to interdict Taiwanese ground forces behind the line for relatively very little cost. The answer is ground based air defense systems mobile enough to move rapidly but with enough power to shoot accurately to high altitudes. The US needs to start a major initiative to expand Taiwan’s current PATRIOT inventory and enhance training.

4. In contrast, US airpower generally had a very limited ability to influence ground combat. For Taiwan, Japan, and the US, the sparse availability of airbase options is a serious problem compounded by the lack of hardened aircraft shelters. These factors meant that in general, a staggering 90% of the total Allied aircraft losses occurred on the ground. As CSIS points out, Allied air bases are under constant missile attack, hospitals are overflowing with wounded, and the flaming wreckage of previous squadrons is simply bulldozed off to the side of the runway to continue air ops.

The US needs to embark on a major effort to establish more bases along the first island chain and harden them. Additionally, the US Air Force must make a difficult mental switch to appreciate bombers as much as fighters. The bombers are able to base far outside the Chinese threat zone, load massive amounts of missiles, and fire at standoff, all while reloading faster than submarine platforms.

5. Even with base case scenario assumptions that missile defense works very well (a single interceptor scoring a roughly 70% chance to knock out a single incoming missile), the volume of incoming missile fire overpowered missile defenses relatively easily. This factor wreaks havoc with surface fleets on both sides.

The US Navy must make an excruciating mental switch away from large ships. Smaller ships are harder to detect, more survivable, and can still be armed with long range missiles. However, the Navy steams in the opposite direction. As Navy Matters has astutely pointed out, one can simply observe the growth in the frigate type of warships over time, one of the smallest types the US Navy builds. The original WWII Buckley class frigates were 1,700 tons, quite light. Unbelievably, the new Constellation class under development is an astonishing 7,300 tons. The Navy’s lightest warship has grown over four times in size, and at over $1 billion per platform, is certainly not affordable nor easy to replace in a casualty intense environment.

6. In every iteration, China was able to achieve tactical surprise and land some amount of troops onto Taiwan. The US will not have much time to make critical intervention decisions. When the conflict initiates, the US is unable to effect cargo vessel supply or airdrop/lift into Taiwan. In one iteration, two out of three battalions of a US Army brigade were destroyed mid-air in an attempt to land ground combat power onto the island.

If Taiwanese forces fight well, they are able to buy some time for US intervention. Chinese forces will require a period of significant combat before occupying major cities. However, If US forces do not get involved early in the first week (D-day to D+6), China is generally in a significantly better position to advance rapidly.

The US must consider measures to base ground fighting forces on Taiwan. While Beijing has declared this to be a supposed redline, it is less destabilizing than stationing strike assets on the island and highly trained ground forces are the one capability that is most able to directly affect the outcome. US strategists realized this during the Cold War along the inner-German border and realize it today along the Korean demilitarized zone. It is a simple and cheap solution to a complex problem which is growing out of control.

7. After analyzing the situation, Chinese red force players decided to land in the south in 21 of 24 iterations. At game start, the heavily urbanized north third of the island contained about half of Taiwan’s total ground force and most of the heavier mechanized units. In contrast, the southern third contained more ports and lighter Taiwanese forces.

The historical record weakly supports the preference for a southern approach. Out of 6 major historical invasions of Taiwan, the Zheng, Qing, and first Dutch invasions were from a southerly approach and successful. The French and second Dutch invasions were from the north and unsuccessful. The Japanese invasion was also from the north but successful. Interestingly, the planned US invasion of Japanese Taiwan in WWII, Operation Causeway, also envisioned a southerly approach.

What are the Lessons for China?

Deep Chinese advantages include missile magazine depth, quantity of 4th gen fighters, availability of air bases, and industrial capacity. Thinking past an operational defeat and towards the long strategic game, Beijing could believe a stalemate benefits China.

The PLA could possibly aim to attrite Allied platforms and expend missiles inventories, then invade in order to maintain an island stalemate for months. In the meantime, the Chinese Defense Industrial Base (DIB) could possibly ramp up quickly to outproduce the Allies. There is a reason that CSIS entitled their study “The First Battle of the Next War.”

Lessons for Taiwan?

The fate of nations rides on the shoulders of the Taiwanese Army and Marine Corps. Virtually all of Taiwan’s air and sea platforms are destroyed within a week, leaving the ground forces to contain the invasion to the beacheads and failing that, fight a savage resistance along every river and ridgeline.

Unfortunately for Taipei, this effort is necessary but not sufficient. Washington will be required to intervene for Taiwan to maintain its autonomy.

Lessons for Japan?

Japan is in a unique position. Japanese military forces certainly help the Allied cause, but far more important are bases on Japanese soil. Without these bases, China has a real chance of winning the war. While it is clear from Tokyo’s recent revolution in strategic affairs that Japan is highly likely to fight alongside the US, the Japanese people will pay a terrible cost. Unlike the US, the Japanese homeland will come under intense direct fire (and potentially assault) for the first time since WWII.

Washington and Tokyo both understand this fact, and it will likely give Japan far more leverage in the relationship than it had previously. In fact, Japan is likely to become Washington’s closest ally bar none in the coming decade, throwing the (supposed) traditional Europe-first strategy on its head.

Lesson for the US?

Victory is within Washington’s reach. It must simply take the actions necessary to grasp it. There must be no doubt that the US is strong enough to win a war against China. It is only by building this strength that the world can hope to avoid war and deter Beijing.