#24 - Chains of Destiny

岛链 - dao3lian4 - Island Chain

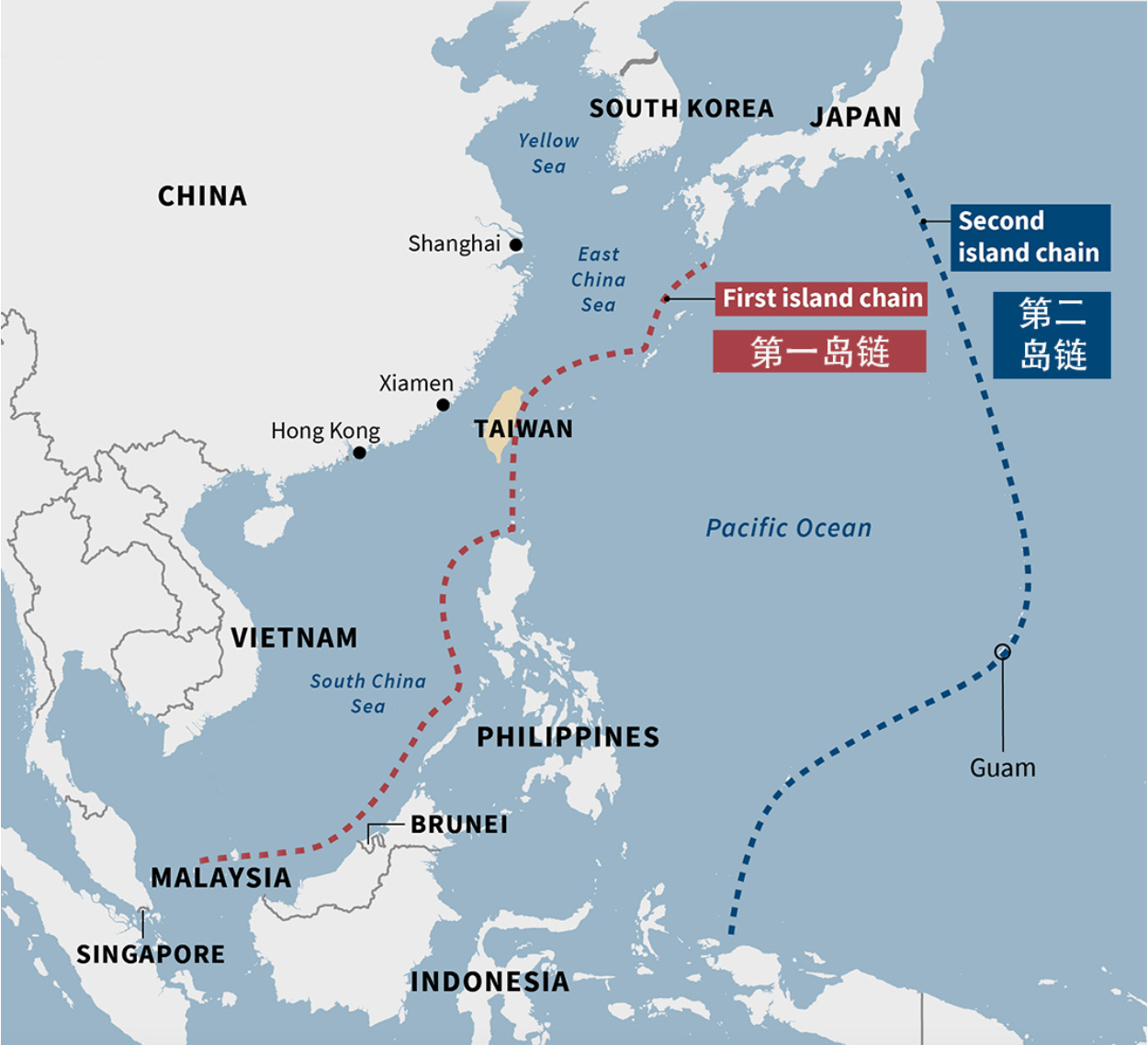

Within the circles of China and defense experts there has been much talk of the first island chain (FIC) and second island chain (SIC) over the past ten years. These obscure archipelagic lines will almost certainly become the most important geopolitical regions on the globe in the coming decades, analogous to the inner-German border during the Cold War. Unfortunately, confusion on the specific geography and importance of these features still reigns. This post will discuss the details of the FIC and SIC, bringing both into sharp focus.

History of the Idea

The island chain concept took root in Imperial Japanese operational thought after the 1942 Midway defeat. With Tokyo forced to adopt a strategic defense, Japanese war planners confronted two obstacles unique in military history. First, they had to consider the Pacific Ocean in its entirety as a military theater. Second, the task of defending against further US attacks relied on occupying not specific cities, mountains, rivers, or other traditionally recognizable defensible features, but extended chains of incredibly isolated islands spanning thousands of miles.

The US, after victoriously fighting through these Japanese defensive belts, then faced a jarring truth. The victory over Tokyo and Berlin flung Washington into adjacent military contact with the Soviet Union and Communist China, partially fueling the Cold War. The question for the US was now similar to the predicament of formerly Imperial Japan. How would Washington defend these oceanic positions against continental powers projecting combat force across the Pacific?

Under the Truman and Eisenhower administrations, special advisor and later Secretary of State John Foster Dulles developed the explicit island chain concept we’re familiar with today. Blending the Japanese and American experiences in WWII and applying them to a Cold War defense oriented westward, the idea of the first and second island chains was born. Dulles intended the concept to illustrate a military and economic defensive line of US allies and partners against Communism.

The FIC and SIC concept has stood the test of time since the 1950s and informs the modern US military operational approach to the Asia Pacific. US military bases and territories on the FIC/SIC were achieved at a great cost in US national blood and treasure. It would be folly to abandon them.

Two further notes. First, it should be remembered that the island chain concept does not originate from a Chinese phrase. Second, Vermilion is proposing small modifications to the FIC concept which preserve its value as a logically and geographically coherent idea to apply to 21st century great power competition between the US, China, and Russia.

Geography of the First Island Chain (FIC)

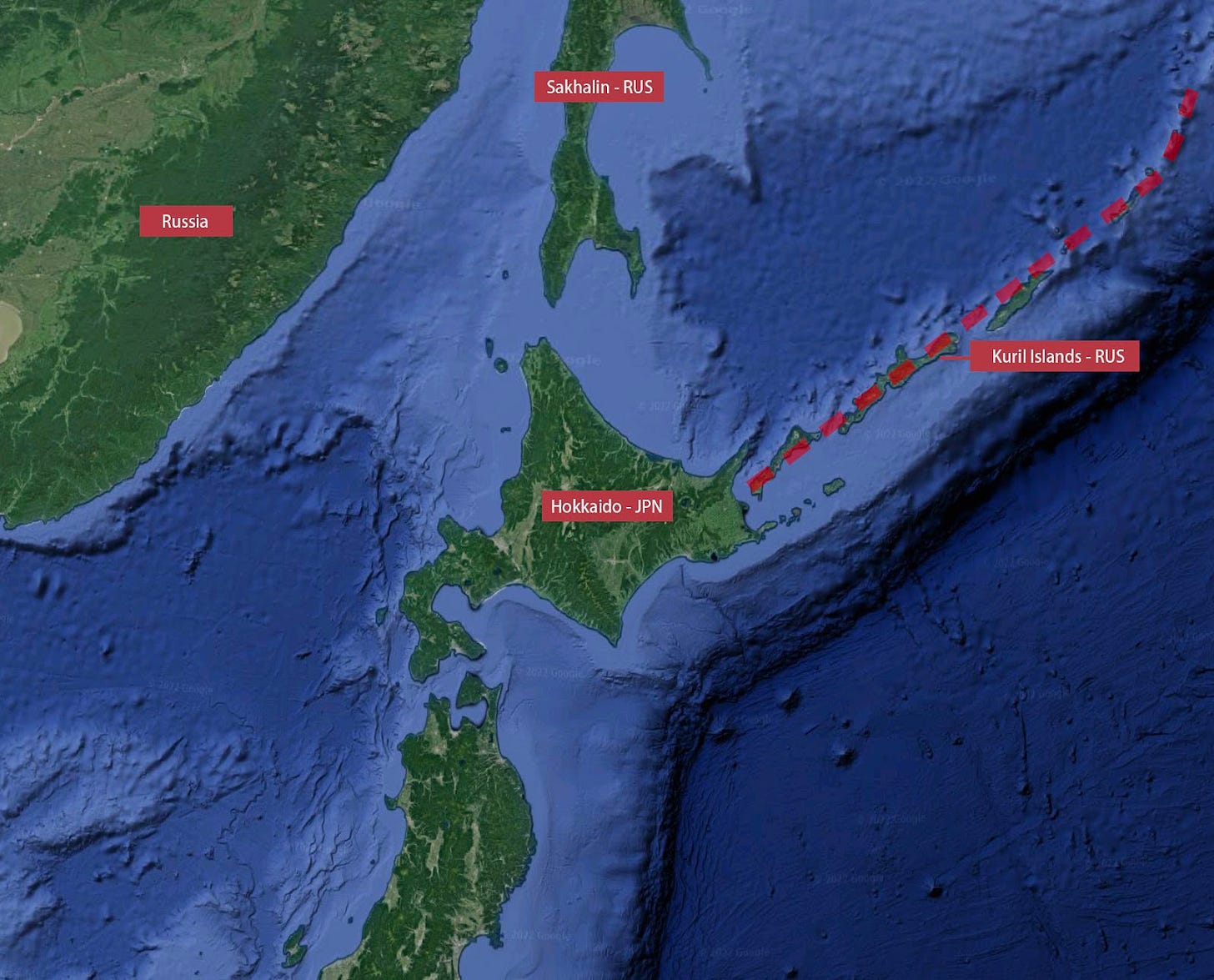

The northern end of the FIC is primarily Russian. The continental anchor is the Kamchatka peninsula, with the first insular portion comprised of the Kuril Islands, volcanic and lightly populated. Some depictions of the FIC do not contain the Kurils, which is an anachronism that urgently requires updating. When Dulles developed the FIC term in 1951, it was primarily aimed at containing the USSR, thus the Kuril chain was ignored since the Soviets seized the islands from Japan in 1945 and forcibly expelled the entire Japanese civilian population in 1946. Yet the Kuril Islands form a logical and geological northern terminus of the FIC that can’t be ignored simply because an adversary occupies it.

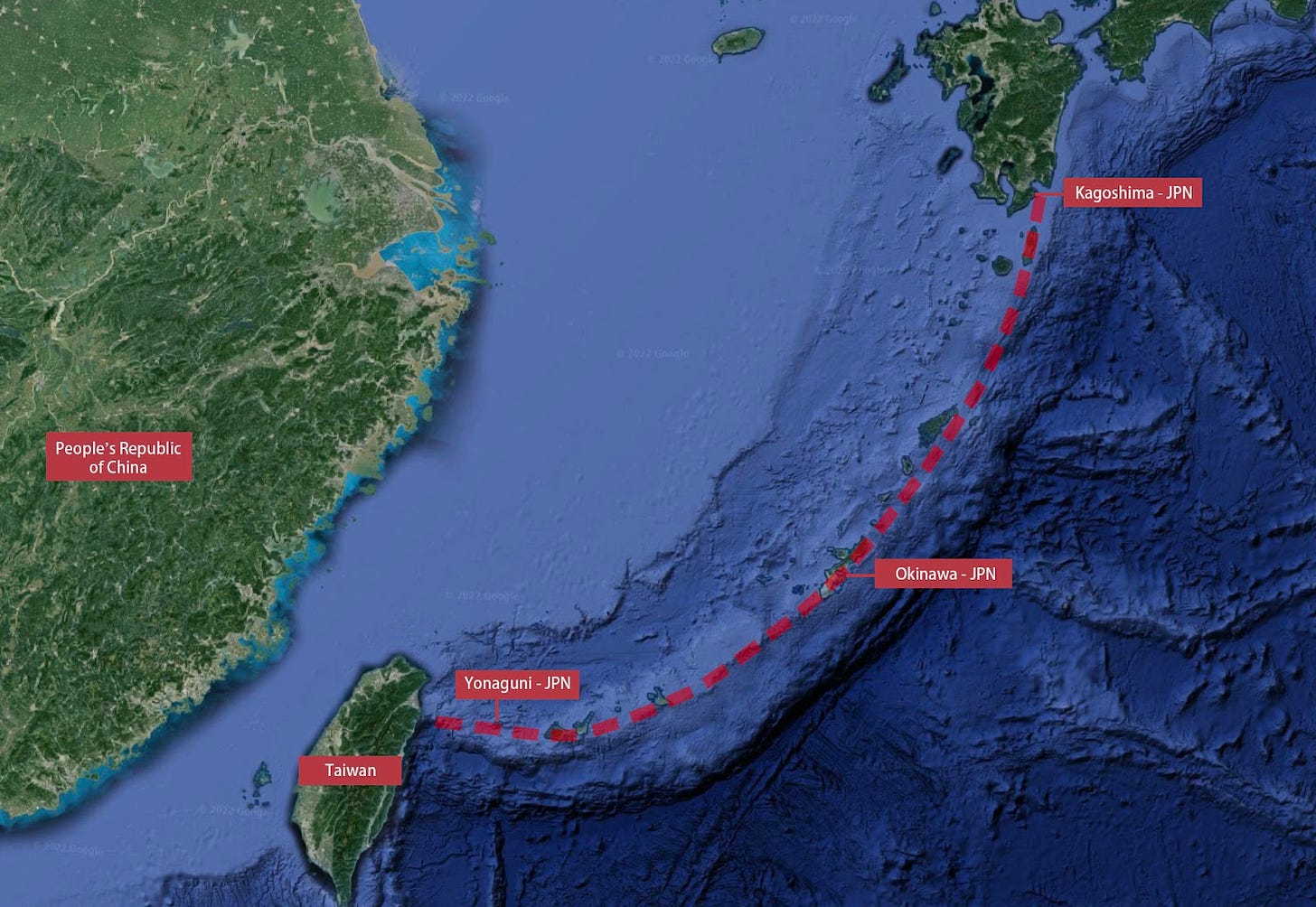

The Kurils arc southwest until they link up with the four main Japanese home islands stacked directly on one another. From north to south, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu.

The Ryukyu island chain then begins just south of Kyushu. Independent from Japan for centuries, the inhabitants are a mix of local Ryukyuans and Japanese who see Okinawa as the cultural heart of their island chain. Just below Okinawa itself are Japan’s Southwest Islands, a series of small islands featuring villages and fishing towns. The farthest southwest island is tiny Yonaguni, a scant 100km from Taiwan.

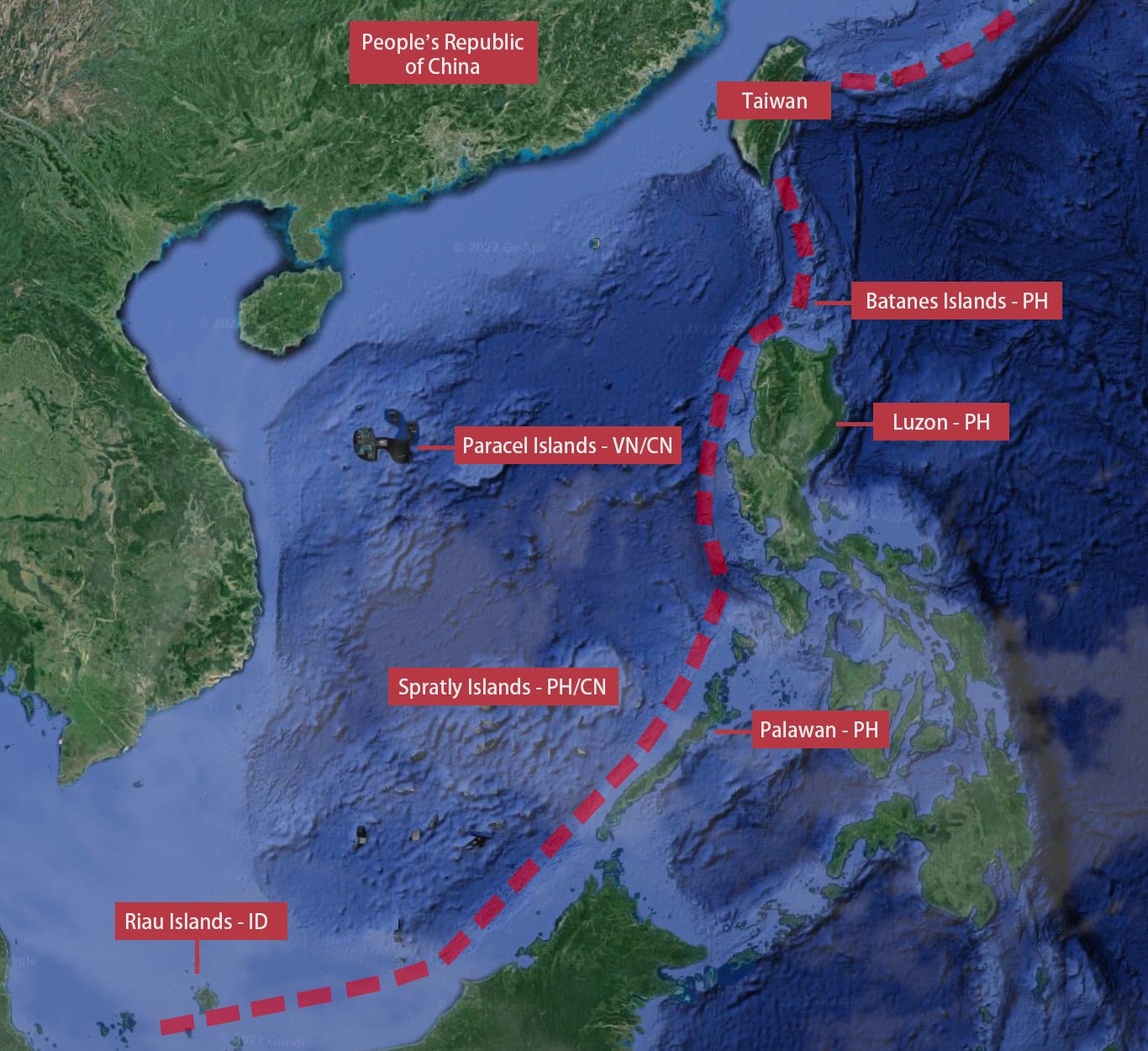

Taiwan forms the archstone of the FIC for many reasons, and possesses many outlying islands itself. Continuing roughly 160km south/southeast lies Batanes province, the northernmost province of the Philippines composed of a series of small islands.

The line of the FIC then cuts across Luzon, Philippines’ northern main island and skips south/southwest to Palawan. This long, thin island (also of the Philippines) forms the eastern flank of the South China Sea. Just 50km due south of Palawan is the largest island in Asia, Borneo. It is the rainforest home of three countries: Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Just off Borneo’s western tip are Indonesia’s Riau Islands, which Vermilion asserts are the true end of the FIC and the cork at the bottom of the South China Sea. Depictions of the FIC typically end with the chain shooting across the bottom of the South China Sea and hooking back northwards to Vietnam ending in Cam Ranh Bay. This is another anachronism since in 1951 Vietnam was incorporated into Indochina, a colony of the Allied power of France. It would have made sense for Dulles to anchor his defensive chain in an ally.

However, since the FIC is an island chain, it should logically not contain the continental anchors of Vietnam in the South nor Kamchatka in the north. Vermilion simplified the chain to terminate in the Riau Islands (specifically at the main island of Natuna) because it is geologically logical and also viewed by China as an area of strategic importance adjacent to the South China Sea, a water feature meant to be fully enclosed by the FIC.

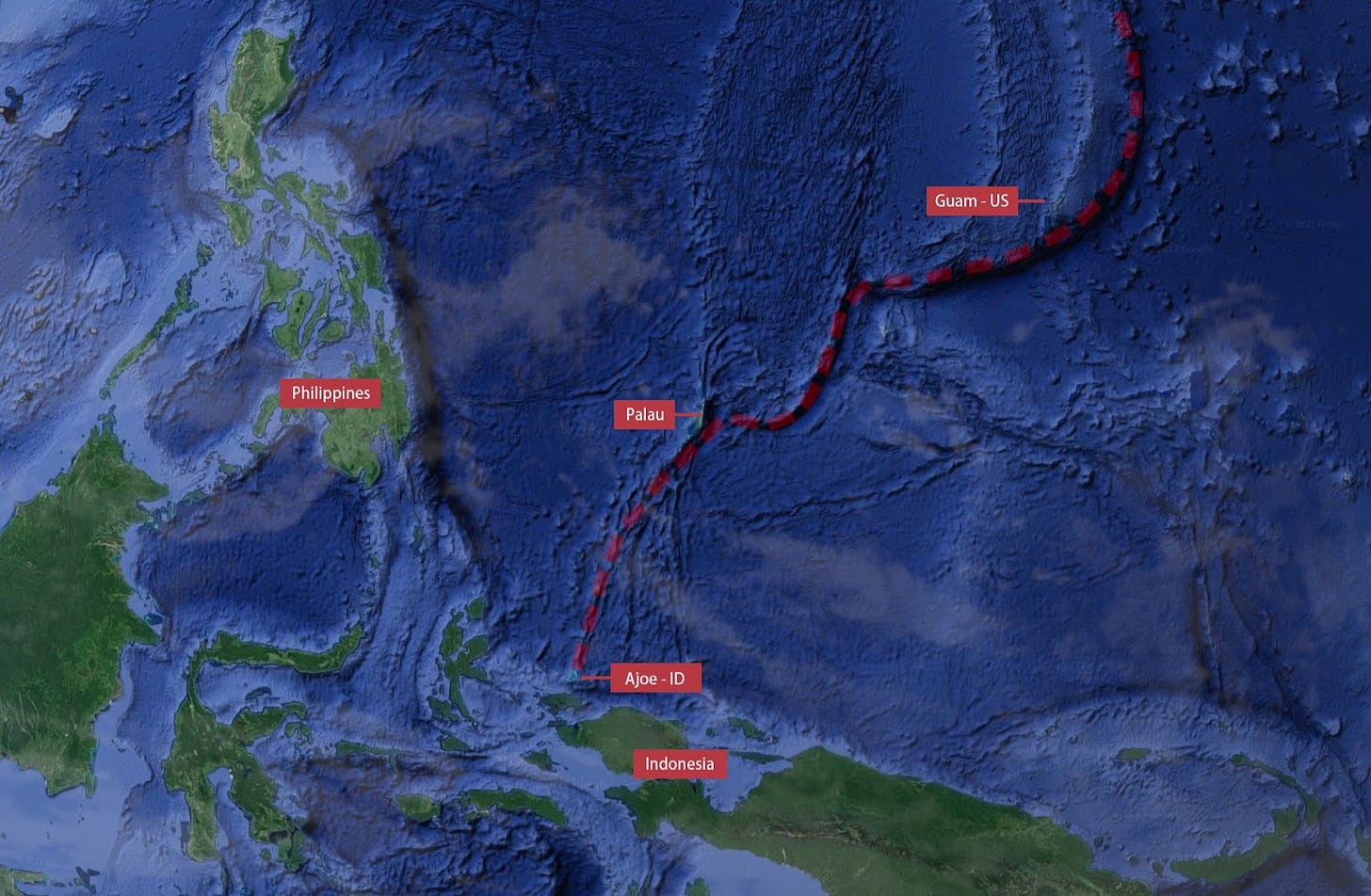

Geography of the Second Island Chain (SIC)

Compared to the first island chain, the SIC is vastly tinier in land area, population, and economic resources. Anchored in the north by the Japanese home island of Honshu as well as the Izu Islands, it then travels south along the Ogasawara Islands along the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc, passing by Iwo Jima and going down through the Marianas (Saipan, Tinian, Rota, Guam). The Marianas Islands are US soil, home to an American city on Guam of roughly 140,000 people. Once the arc hits the Palau Ridge, the SIC shoots south down through the island of Palau and terminates in the Ajoe Islands (Indonesian territory), with the southern anchor being the island of New Guinea, host to the countries of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

Third Island Chain (TIC)

Vermilion pushes back against the concept and existence of a TIC. The supposed TIC sometimes includes the Alaskan Aleutian Islands and sometimes not. The heart is supposed to be the Hawaiian chain, which is universally noted as quite isolated and not adjacent to any other group of islands. There is no geographic, bathymetric, or seamount analysis that creates a logical TIC. However, there are logical blocks and chains of islands throughout the region east of the SIC, they simply do not form their own clusters and not a third chain. These blocks and chains include Kiribati, the Tonga-Kermadec Ridge, New Caledonia, Solomon Islands, the Samoas, and many other regions.

Importance of the First and Second Island Chains

The island chains matter for two reasons: battle networks and logistics. As the amount of Blue (US) increases on any map of a military theater, the value of the Green (allies) greatly increases. When there is very little dry land to marshal forces, refuel, resupply, and establish headquarters, small islands have outsize importance.

Modern war relies on battle networks of connected sensors (radars, satellites, drones, scouts) supplying target quality information to shooters (platforms firing missiles and artillery). While a portion of the network can operate in the air or at sea, these platforms are generally quite expensive.

The FIC and SIC are also crucial for logistics. The basing of sensors, as well as the rearmament, refueling, and remanning of all platforms requires land. Even submarines and other long endurance capabilities require supply nodes. Ultimately, if a sensor or platform is mobile, it is critically affected by sortie rate, and the closer the supply nodes are to the front line, and the more basing options available, the higher the sortie rate (the rate at which a sensor/platform can travel to the fight, fight, then turn back and get ready again).

Not only do bases along the FIC and SIC enhance sortie rates, they are excellent for basing ground forces. Consider land-based anti-ship missiles. Compared to air and sea platforms, land-based variants (HIMARS, Hsiung Feng III, NMESIS, etc) are far cheaper to manufacture per platform and far cheaper to make difficult to find. These land-based missiles have the capability to deny the waters of the FIC to Chinese and Russian vessels until more exquisite air and sea platforms deliver the decisive blow.

In the current geopolitical context, the island chains are essential for the same reasons they were invented in the 1950s. US military use of the FIC/SIC prevents Russia and China from moving any significant combat power eastward. With an inability to move combat power, Beijing and Moscow are unable to coerce neighboring nations. Without this coercion, they are both unable to invade allies or partners and/or distort the international rules-based system to their abusive favor.

How the Communist Party of China Thinks

Historically, China has seen itself as an exclusively continental power. Outside of civil wars, the vast majority of historical conflict in the region took place in the Mongolian steppe, Northern Korea, Northern Vietnam, Xinjiang, and Tibet. Long distance maritime interaction with other peoples was almost entirely limited to Zheng He’s voyages in the 15th century. In fact, the Ming Empire imposed a blanket ban on sea trade (海禁) to stop pirate raids, effectively blunting any incentive for Chinese maritime exploration. This ban continued with the Qing Empire until the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century. The only significant maritime action from the 15th to the 20th century was the Qing Empire’s defeat of Koxinga (a Ming loyalist/Zheng general) in Taiwan. In the accomplishment of this objective the Qing temporarily ordered nearly the entire coastal population of China inland from 1661 to 1683, further alienating the Chinese people from the sea.

Post 1949 Chinese Civil War, Beijing’s continental focus slowly moved seaward. The CCP’s efforts to solidify China’s land borders generally paid off (excluding notable friction points with India), allowing the CCP to begin pursuing other priorities.

As the CCP gazed eastward, it became critically aware of China’s maritime low ground on her own coast and within the FIC. China controls no portion of the FIC and is therefore at acute risk of maritime blockade. Simultaneously, China lacks any significant buffer zones for the control of her own coastal provinces. These provinces were the original weak points which served as the entrepots of European imperial powers forcing mercantile trade upon the Qing dynasty.

Just as in the age of sail, military forces operating from the FIC are a critical perceived vulnerability for the CCP. Today, modern radars, drones, aircraft, and sea vessels have far more range and endurance than gunboats from the 19th century, heightening the CCP’s threat perceptions. At its closest point, the FIC is a mere 80 miles from mainland China, and nearly all major Chinese ports are theoretically within missile range from multiple firing positions along the FIC. Founded on these insecurities and fueled by the ambition to secure core interests, the CCP is compelled to take control of the FIC as its military power grows.