We’re All Retarded - China and America are Terrible Strategists

This series will discuss the strategic blindness apparent on both sides of the Pacific. In this first article, we focus on Beijing. The CCP aims to become a seapower. Is this realistic?

Strategic planners in Beijing should remember that sea power requires domestic political consent to effectively deploy power abroad. It is political consent which forms the necessary foundation to 1) convert national resources into expeditionary power abroad and agree on common goals for the use of this power (even when such decisions are in error as in Athens’ Sicilian Expedition of 415-413 BC), 2) minimize other government expenditures to fund fleet activities, and 3) have confidence in the seafaring nation’s domestic order so that expeditionary forces are not overly influenced by potentially subversive political ideas.

1) Convert national resources into expeditionary power abroad and agree on common goals for the use of this power

If the CCP thinks that its current People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) battle force of 234 warships or its supposed future battle force of 400 is sufficient, it is deluding itself. The PLAN will likely require thousands of warships to win a decisive victory in the Pacific. The construction of such a fleet would require tremendous financial and material resources, both of which would strain the PRC to the limit.

The US required over 6,000 ships to win WWII in 1944/1945, including 28 fleet carriers and 71 escort carriers.

There are reasons to believe even more vessels would be required. Today, potential combatant nations are much larger. China’s population in 1940 was roughly 440M, today 1.4B. The US population in 1940 was 132M, today 347M. Both nations have more resources to convert into naval power than in 1940.

There are also good reasons to believe fewer vessels would be required. In a modern naval war, many vessels would be drones, and the PLA may not contemplate fighting past the second island chain (SIC). There may also not be major operations in Europe.

These factors could lead us to cut potential wartime requirements very roughly by 50% - still leaving a force of 3,000 vessels required to win a major modern naval conflict in the Pacific.

Even with more resources available compared to 1940, how would the PRC finance such an effort? China maintains an economy mostly walled off from the outside world. This allows the CCP to exert leverage over its citizens and sabotage non-PRC companies, but makes it incredibly difficult for the PRC to order its finances transparently and maximize government credit.

The fact remains that fleets are and always will be incredibly expensive. The US Navy’s Operations & Maintenance (O&M) budget request for FY26 is roughly $71B, including $16B specifically earmarked for maintenance activities. These are costs incurred at a time when the US Navy is the smallest it has been since 1930, on the eve of WWII. For a sense of scope, the entire Japanese defense budget request for FY26 is $60B.

About 70% of the PLAN fleet is 10 years or younger, which is an advantage today but erodes every year as older ships require more maintenance. The US Navy is not yet in its “breakout” or “naval buildup” phase.

This means the PLAN must prepare its current and projected fleet to eventually fight a newer, more technologically advanced American fleet composed of future types of warships (called classes of warships) well suited to modern naval combat.

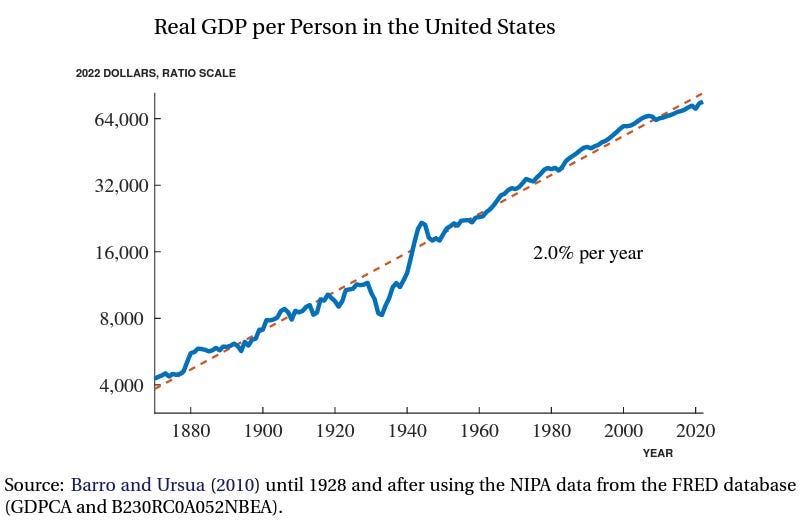

But what are the financial resources available to the US and the PRC? The US maintains by far the largest financial market with $62T in market capitalization, compared to the PRC’s $11T. In terms of the wider economy, US GDP growth is unlikely to deviate from 2% per year, as evidenced by data from 1880 to today.

While it is hard to envision how the PRC could muster the financial resources to maintain a fleet capable of winning, it is equally difficult to see how it could actually construct such a fleet during wartime.

It is common to point out the PRC’s civilian shipbuilding advantage, but it will be very difficult for the PRC to convert this advantage into a permanent lead in warship production moving forward.

The US shipbuilding industry is in the process of moving from complete neglect to a top priority, and this is unlikely to change in the future. Additionally, South Korean and Japanese shipbuilding match China’s output, both natural adversaries of Beijing. The US has a global network of allies and partners to leverage in its shipbuilding initiatives, including Australia, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and France.

The PLAN is almost certainly unable to contest control of the Atlantic Ocean or far-flung sea lines of communication (SLOCs), meaning that Beijing will be unable to prevent the US from controlling most of the global commons both nations rely on for importing shipbuilding materials in wartime.

Finally, there must be a widespread and overriding belief in expeditionary naval power to maintain its existence. Athens, Great Britain, and modern America had/have deep beliefs about trade, the importance of the sea, and geographic positions that require large naval forces as a primary priority. China lacks all of these. Indeed, the last two times that Chinese rulers convened major concentrations of naval power, the efforts ended in abysmal failure.

In the 15th century, the Ming Dynasty built a force of over 2,000 ships and engaged in extensive maritime diplomacy and expedition activity. While the success of this activity is not in dispute, the dynasty would eventually dismantle the fleet and turn its mariners over to domestic riverine operations.

Arguments for the dissolution of the fleet include the high cost of maintenance and political conflict in the Ming Court over the power of the court versus the eunuchs who commanded the Ming fleet. The Mings lacked the financial resources and widespread common cause for maintaining naval power.

In the 19th century, the Qing Dynasty created the Imperial Fleet (one portion of which was the Beiyang Fleet that our readers will be familiar with). Once again, the cost of the fleet proved too high, with the Qing Imperial Fleet falling behind in modernization and suffering defeat at the Battle of the Yalu against the Imperial Japanese fleet in 1894. In the aftermath of Yalu, Chinese rulers once again mostly dismantled the fleet and turned a portion of it over to domestic riverine duties.

2) Minimize other government expenditures to fund fleet activities

As we have discussed, funding naval expeditionary power is a distressingly expensive enterprise. Yet China is fundamentally a tellurocracy or land power, deriving strength from its continental position and control of China’s rivers. Historically, China’s rulers have spent the vast majority of their strategic means attempting to control the continent and keep China united.

To maintain this massive and culturally fragmented area, rulers in Beijing must rely heavily on the oppression of their own population. This requires resources, and this oppression tax weighs heavily on Beijing’s budgetary resources.

The PRC’s domestic security spending almost certainly outstrips its military budget. In fact, the PRC stopped publishing domestic security figures in 2014, likely due to the optics of a rising great power required to apportion so many budgetary resources to internal social stability problems versus external ambitions.

The PRC’s potential fiscal ramp to generate naval power is tightly constrained by domestic political factors, which the US can influence.

3) Have confidence in the seafaring nation’s domestic order so that expeditionary forces are not overly influenced by potentially subversive political ideas abroad

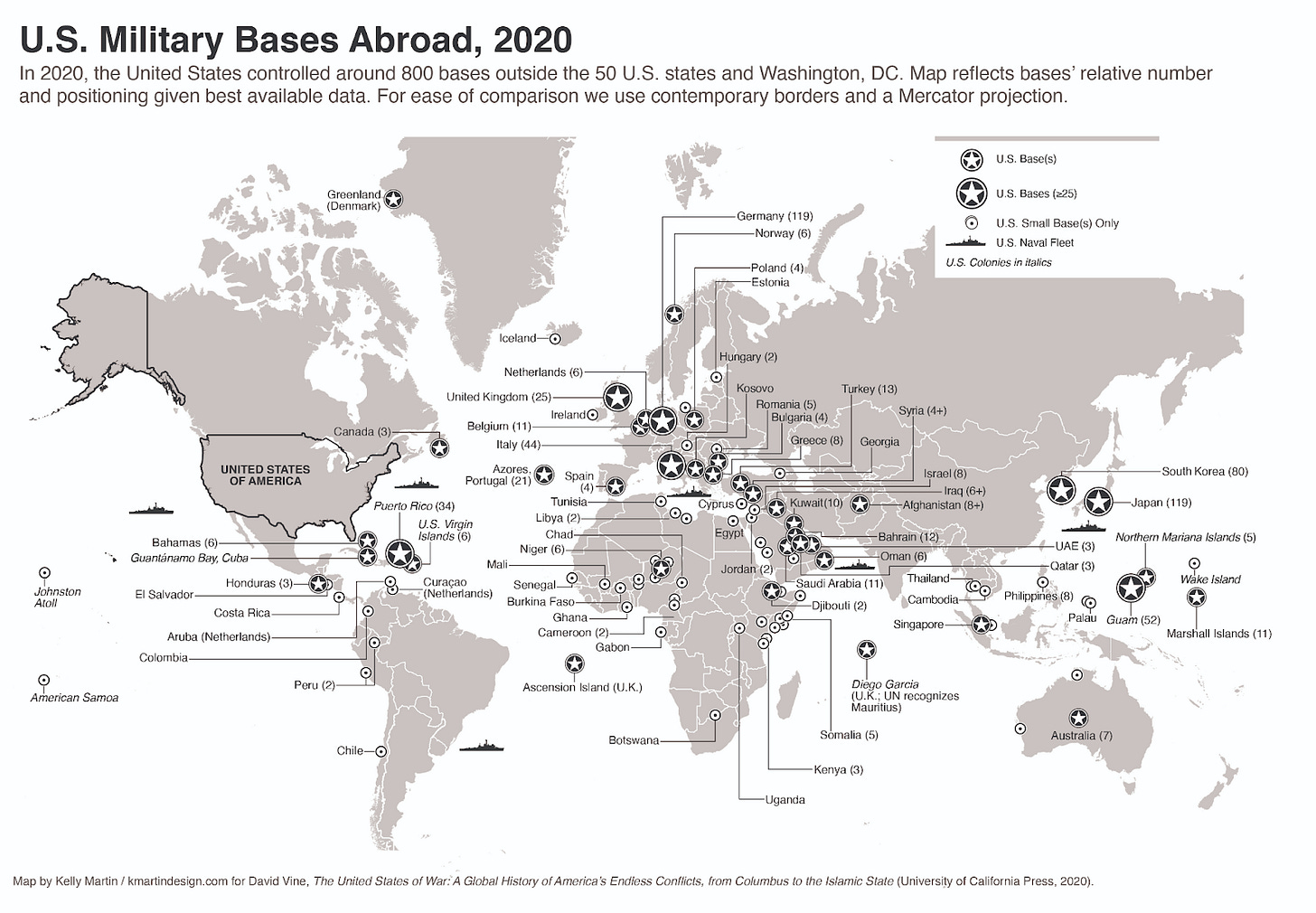

Any modern naval expeditionary force must rely on a global network of naval bases to support fleet activities.

In the past, the British Navy’s major imperial coaling stations included Gibraltar, Malta, Port Said, Aden, Colombo, Singapore, Hong Kong, Bermuda, Jamaica, St. Helena, and Ascension Island. The modern US military has improved upon this footprint and maintains about 800 bases supporting global military activities.

The PLA has nowhere near this level of basing abroad, and it is difficult to see how it could even develop one in the future.

Even if the PLA had such a basing infrastructure, the CCP would have to station party members and PLA officers abroad, which would harm domestic social stability. PLA mariners and marines abroad would be exposed to new ideas about government and views not restricted by the Great Firewall, China’s censorship apparatus.

This is exactly what happened to Sparta in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War. From historian Arnold Toynbee:

“Now that Sparta had inherited from Athens a domination over the entire Hellenic world, she found herself compelled to second her [Spartans] from military service, from which they could not safely be spared, to non-military duties with which they could not safely be entrusted.”

Spartans had to be stationed overseas, leading to many officers enriching themselves and straying far from the Lycurgic system. The number of Spartan equals (or homoioi) would continue to drop year after year until 371 BC, when only about 700 Spartan hoplites could be fielded at the Battle of Leuctra, leading to Sparta’s defeat at the hands of Thebes.

Outlook

Just because these limiting factors exist does not mean that the CCP won’t try, and that containing Beijing’s ambitions won’t be costly - simply that the efforts are quixotic.

That such an inward-facing telluric power dares to have expansive external goals - invasion of Taiwan, control of the high seas, and placing Beijing at the center of the international maritime system - speaks to a gaping chasm between means and ends.

This chasm often disposes great powers (particularly adversaries of the US) towards overly risky aggression. Imperial Germany’s anxieties about the Entente, Russian economic development, and Social Darwinism made Kaiser Wilhelm II launch Germany into a disastrous world war.

Imperial Japan’s fatalistic attitude towards growing US power convinced Tokyo to take action and go on the offensive when it was explicitly against Japan’s strategic interests in WWII.

Beijing is so far content to play the role of the needlessly aggressive and overly anxious US adversary, whose strategic designs plant the seeds of their own failure.