We Were Once Masters of the Air

It's High Time to Restore US Air Power

The American people do not want a war with China. In order to prevent the outbreak of war, the US must deter the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from initiating combat operations against their own neighbors. To do this, the US must credibly communicate to CCP decision makers that U.S. capabilities would force China to lose in combat.

It is the Chinese perception of launching unsuccessful combat operations that will prevent the outbreak of war. China has an excellent intelligence arm which observes the U.S. military. Washington can use this to its advantage by fielding a credible minimum capability to fight and win a defensive war against China. This will put doubt into Chinese decision maker's minds.

An important domain of warfare in any US-China conflict scenario is the air. Fighting in the air is platform-centric, meaning that vehicles (fighters, bombers, etc) are required to conduct operations. The way the U.S. military fights wars is divided into six phases: shaping, deterring, seizing the initiative, dominating, stabilizing, enabling civilian authority, and then a return to shaping.

Air power plays a role in every phase, but is absolutely essential in the deterring, seizing the initiative, and dominating phases. Without robust air power, U.S. forces are unlikely to be capable of wresting the initiative from an attacking China, which almost certainly would strike first in a wartime scenario. If U.S. military forces cannot credibly rely on seizing the initiative, then they are both unable to deter China and unable to transition to the dominating phase of decisive victory.

Air forces are essential to seizing the initiative because they are far more speedy and agile than ground or naval forces (this does not mean strong ground/naval forces are not required). Air capabilities provide critical firepower, overwatch, and intelligence to ground and naval units without which they are sitting ducks.

Since war in the skies requires platforms which are expensive and hard to replace, seizing air superiority against a peer adversary is often a short, sharp, and decisive battle within the larger and slower process of a single war. Historical examples abound. The Nazi invasion of France in 1940 was made possible by the Luftwaffe’s rapid grasp of air superiority and then supremacy over the continent. The Luftwaffe helped German forces seize the initiative early, and aided in the eventual decisive operations at the Battle of Sedan and the three panzer corps attack which isolated the allied force at Dunkirk. The entire Battle for France lasted only six weeks.

In the Battle of Britain, the Germans were unable to achieve more than air parity with Great Britain. This failure to seize the air initiative led to the cancellation of Hitler’s decisive follow-on operation, the amphibious invasion of England. The Battle of Britain lasted less than 4 months.

Additional examples include the air war over the eastern (In the first few days of the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Luftwaffe destroyed some 2,000 Soviet aircraft, most on the ground, at a loss of only 35 German planes) and western fronts, the Pacific, the later Israeli Six Day War (Israel achieved air supremacy against both Egypt and Syria in a single 24-hour period), and the Gulf War. In these cases, destroying aircraft on the ground, runways, and maintenance facilities did the great bulk of effective damage, not necessarily air-to-air combat.

Considering the American experience, seizing the initiative against China would be more difficult than doing the same against Serbia, Iraq, Afghanistan, or ISIS since none of those adversaries fielded a modern professional air force. Air combat against China is more likely to resemble WWII fighting against Germany, Italy, or Japan.

Russia’s inability to gain air supremacy over Ukraine in the face of modern air defense and intelligence platforms should equally give American military planners pause.

Correlation of Forces

General Mark D. Kelly, current head of Air Combat Command, has clearly stated that the U.S. Air Force has lost conventional overmatch against Chinese air and space forces. Much of this is due to relative aircraft quantity. As of 2022, it is estimated that China had a total first-line combat aircraft inventory (FLCAI) of around 2,400 planes according to the China Military Power Report. These are fighting aircraft not support platforms, which includes fighter, bomber, and attack types. The US FLCAI is roughly 900 for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, which must be added to 2,300 for the U.S. Air Force for a combined 3,200.

For a sense of scale in great power conflict, it is estimated that Imperial Japan’s FLCAI in 1941 (Imperial Japanese Army Air Force & Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force) was about 3,200 aircraft. On the U.S. side, the U.S. Army Air Corps’ FLCAI alone matched Japan at 3,200 aircraft while the U.S. Navy’s FLCAI of 1,600 leads to a combined 1941 U.S. total FLCAI of 4,800.

There are two major wrinkles in these numbers. The first is combat-coding and the second is mission-capable rates. Modern aircraft rely on intensive use of high-tech avionics and software. This means that all fighting aircraft have to be about close to the same “software and hardware baseline” in order to communicate securely with friendlies, employ the latest weapons, and employ radar using the latest methods. Trainer aircraft and test & development planes are virtually never kept to combat code.

These differences are not academic. Two aircraft of the same type, model, and series, but with a difference in combat-coding can have radically different capabilities:

“In March 29 testimony before the House Armed Services Committee’s tactical aviation panel, [U.S. Air Force Lt. Gen. Richard G. Moore Jr., vice chief of staff for plans and programs,] said the [F-22A] Block 20s are not “competitive” with the latest Chinese J-20 stealth fighters. And while the aircraft could be used for training, Moore said they are so out of synch with the combat-coded [F-22A] Block 35s that pilots are receiving “negative” training from them, meaning they have to “unlearn” habits developed in the Block 20 before they can become proficient in the Block 35.”

Taking combat-coding into account means the air forces actually ready to fight tonight would be chopped by a conservative 20% (which is generous in the U.S.’ favor). This renders a combat-coded FLCAI for China of about 1,950 and for the US about 2,500.

This group of combat-coded aircraft only represents aircraft that have the possibility to be ready for combat. Regardless of combat coding, not every flying squadron in the U.S. and Chinese armed forces is full-strength on qualified pilots, necessary support personnel, or money for pilot flight hours (seat time), spare parts, and maintenance hours. In many cases, multiple squadrons would have to be merged to create a lesser number of mission-capable squadrons.

To get combat-coded aircraft to mission-capable status would require a 30% cut to each force. Again, this is an extremely conservative cut. There are times when the U.S. Air Force F-22A fleet and U.S. Navy F/A-18E/F fleet drop to incredibly low mission-capable rates hovering around 50-60%.

We are left with a mission-capable, combat-coded FLCAI of 1,400 for China and 1,800 for the U.S. Still, it is unlikely that every single ready aircraft in the U.S. inventory could be dedicated to the China fight. Europe and the Middle East require U.S. air capabilities not only for deterrence, but the brewing Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts. China does not have global responsibilities or a network of allies like the U.S. and can concentrate on the first island chain.

China’s air reserve in a Taiwan scenario would still easily be capable of responding to a crisis against India since the force would be operating from domestic air fields regardless of the threat. In contrast, at least 300 U.S. airframes would have to be retained for a global reserve. This gives a count of 1,400 Chinese fighting planes and 1,500 American.

These realities give China and the US roughly the same amount of mission-capable combat-coded aircraft available to fight tonight. If China chooses to strike first, Beijing would likely have already prepared its air forces, perhaps leading to a Chinese edge in mission-capable or combat-coded inventory, but that won’t be considered for this report.

Obviously this is a terrible strategic situation for Washington. Given this stalemate in numbers, the following factors are key for determining the balance of air power.

Advantage - Allies & Partners - 700 more coalition fighters

The U.S. has far more friends than China, along with a combined (meaning international) aircraft program, the F-35. If Japan and Australia came together to support a US coalition, they could muster perhaps 150 more 5th generation mission-capable combat-coded aircraft. This is not many but every bit helps. Singapore has not received its full allotment of F-35B, currently sitting at around 12 F-35B aircraft. South Korea currently has a total inventory of around 60 F-35A aircraft. In the out years, about 200 ready 5th generation fighters will likely be stationed with allies and partners.

There are obviously more aircraft than just the F-35 in coalition inventories. Roughly 500 more aircraft of dubious 3rd and 4th generation quality are garrisoned throughout the Pacific, which means perhaps 300 ready aircraft could be generated in an emergency. This force would take high casualties in a fight, due to old technology and lower pilot proficiency.

In terms of future allied production allotments, due to current events and Congressional lobbying, Israel will likely ask for and be successful in receiving a number of F-35I ADIR aircraft from Lockheed. As of late 2023, Israel likely has somewhere around 42 aircraft (about 3 squadrons) and Israel’s ask will likely crowd out Pacific allies’ requests, further degrading deterrence against Washington’s pacing threat.

Taiwan itself has a 4th generation fighter force of around 350 planes, of which maybe 200 would be ready to fight tonight. However, Taiwan’s air force is extremely challenged in terms of air base survivability. Protecting against Chinese missile salvo attacks is likely to be difficult.

While coalition fighting airframes are important, more important to the U.S. are the extra airbases and maintenance facilities American forces would potentially have access to Japan, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan, and Singapore. Since each nation is familiar with operating the same airframe (except Taiwan), this is a significant advantage.

U.S. air frames will sustain an incredible amount of stress and damage during high intensity combat operations. Allied airfields are a necessary, though not sufficient key to deterring and winning against China. These extra fighters change the final count to 1,400 Chinese fighting planes and 2,200 coalition (which includes the 1,500 U.S. aircraft).

Unfortunately, it is only because of coalition aircraft that the U.S. can be confident in fighter quantity overmatch. However, the U.S. does not command these aircraft and history suggests that not all of them will be available during a Taiwan emergency. America’s quantitative superiority and service members’ lives lie in the hands of our allies and partners, some of which are not reliable.

Advantage - Pilot Edge

U.S. pilots are almost certainly better trained and of higher quality overall than Chinese pilots. This is likely to be an enduring advantage, though China is attempting to close the gap.

Advantage - U.S. Aerospace Industrial Sector

The U.S. has experience manufacturing military aircraft since WWI. This hundred year history, combined with U.S. defense contractors’ private sector character almost certainly gives Washington the edge over Beijing in terms of combat aircraft quality under actual combat conditions.

When the U.S. defense industry delivers equipment to the American warfighter, it is much more likely to fill the requirement than similar equipment delivered by China’s state-owned defense enterprises.

Disadvantage - U.S. Aerospace Industrial Sector

While the U.S. certainly produces the best aircraft in the world (viewed across all types), the defense aerospace sector has grown first much too consolidated, and then secondly, far more bloated.

The P-51, an American WWII fighter plane, was taken from drawing board to flying prototype in under six months. Total development time from design to finished flying model took less than 2 years. North American Aviation, the company producing the P-51, had never manufactured a fighter before. The P-51 would go on to become the dominant fighter aircraft of WWII.

F-35 design began in 1996 and finished with full-rate production in 2016. 20 years sounds like a long time to design a single aircraft as a mature aerospace firm and a recognized prime defense contractor. Additionally, a single P-51 would cost roughly $880k in today’s dollars (about $51k in 1945 dollars) while the cheapest version of the F-35 (the F-35A) currently costs around $70 million. While there are some good reasons for the increase in price (these two platforms have different capabilities), the fact remains that military hardware is becoming significantly more expensive in a more challenging U.S. fiscal environment.

Another serious concern is the Chinese aerospace industry’s increasing ability to churn out airframes quickly. If the U.S. and China both take serious losses during the outset of war and cannot dominate the skies (like Ukraine and Russia), there is a chance that China will be capable of pumping out less advanced J-10C and J-16 fighters still capable of firing advanced missiles.

Disadvantage - Access, Basing, and Overflight (ABO) & Fighter Support

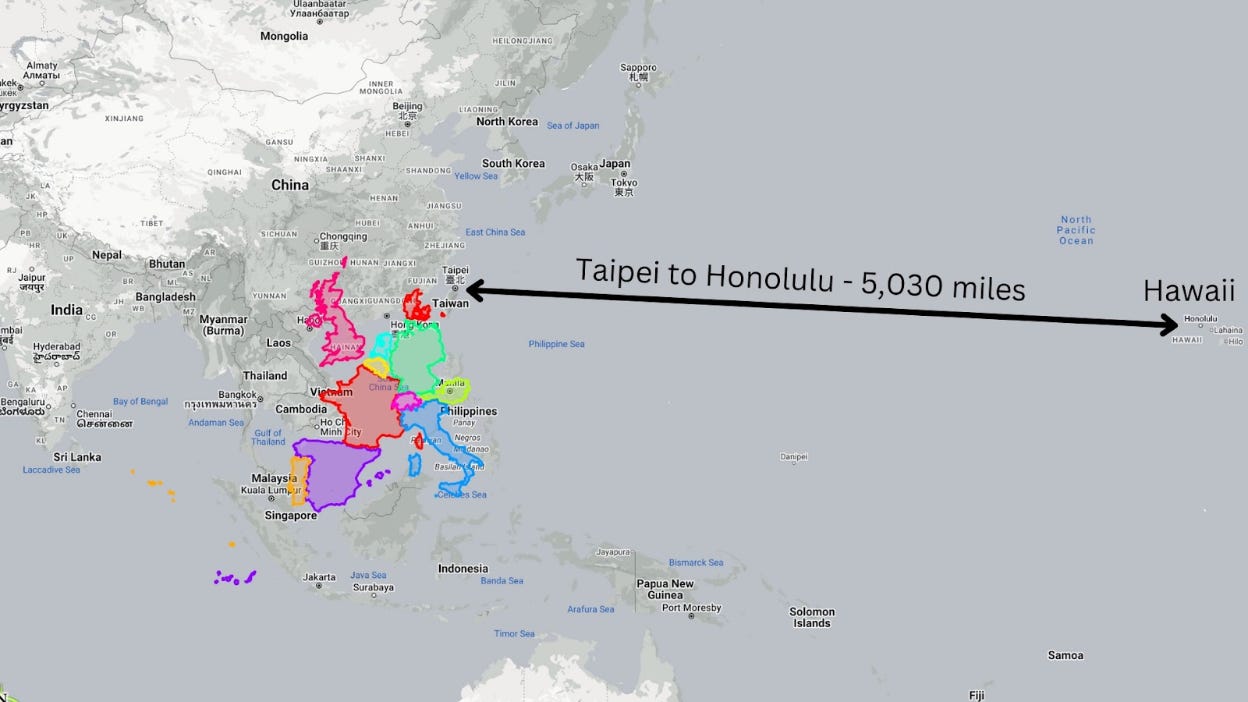

Throughout the Taiwan region and the First Island Chain, U.S. basing options, while not catastrophic, are severely limited. All air bases throughout this region are on foreign soil and within Chinese missile saturation range (Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore). Compared to Chinese or U.S. domestic air bases, U.S. forward options have lower capacity, lower protection, and lower total surface area. These weaknesses make these critical airbases easier for China to knock out with missile strikes.

Putting capability aside, the U.S. must diplomatically achieve permission to use this weak inventory of air bases for offensive operations during war. Countries like the Philippines, Japan, and Taiwan must give Washington permission first, which could have escalatory consequences for the host country.

The difficulties of poor base infrastructure and a lack of control over these same bases is compounded by the extreme distances encountered in the Pacific theater. Fighter aircraft require aerial refueling tanker support or carriers to move throughout the region. The disadvantage of tanker support is mainly the fact that tankers are not in the least bit stealthy, since they have to carry huge volumes of fuel. Chinese radars can easily identify the large refuelers from far away, giving them both the chance to take a shot and also identify where U.S. fighters are operating. China would likely seek to attrite the U.S. tanker fleet in order to cripple U.S. mobility theater-wide.

The disadvantage of carriers is that China has spent twenty years building capabilities to target U.S. carriers far out at sea. Carriers may in fact be obsolete (like WWII battleships, a class that is no longer constructed) due to advances in missile technology. Regardless of vulnerability, losing just a single U.S. aircraft carrier would result in the deaths of 5-6,000 U.S. service members, about double the amount of KIA the U.S. experienced during the war in Afghanistan from 2001-2021. The current force structure of the U.S. military is heavily reliant on these carriers.

Fighter aircraft are also capable of equipping drop tanks to carry extra fuel, but this significantly degrades their stealth / low observability, making them larger targets. Both drop tanks and/or the presence of tankers/carriers make U.S. fighters vulnerable to being detected.

While the U.S. must rely on tankers, carriers, and drop tanks, China needs very little of this sophisticated architecture. Operating from massive fortified airbases (or civilian runways) on home soil, the Chinese air force is far closer to Taiwan and will consume far less fuel and platforms in order to achieve a similar level of effects on the battlefield.

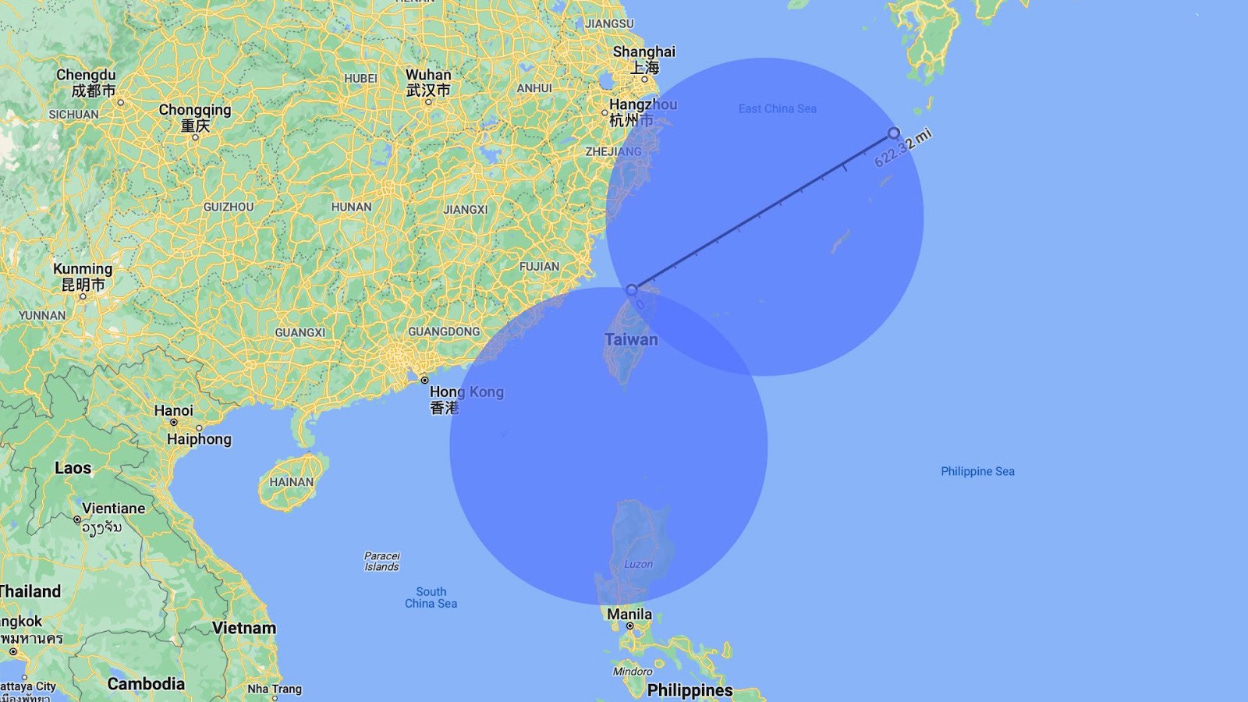

In the above image, the blue circles represent the rough combat radius of the F-35 fighter. This is the unrefueled / no drop tank range. Unless significant tanker aircraft and/or drop tank equipment is employed (both major vulnerabilities which reduce stealth), air base options for the U.S. are severely limited to (1) the tiny Japanese South West Islands, (2) the northern portion of the Philippines’ Luzon island, or (3) Taiwan itself.

Finally, U.S. fighters usually operate with some form of Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C). These special aircraft utilize large radars to find the enemy and coordinate blue forces. AEW&C aircraft are quite large and difficult to hide, even when not emitting radar waves. The presence of an AEW&C can tip off red air forces.

The Chinese military is also fielding AEW&C aircraft, and at ever greater densities. However, Chinese air forces can also rely on cheaper, larger, higher-powered land-based radars to see across the water. These facilities could give Chinese fighters the advantage of increased situational awareness without the vulnerability of an AEW&C flying around.

Disadvantage - Munitions

China has made missile development perhaps the number one modernization priority of their armed forces. Consequently, Chinese missiles across the inventory are comparable and in some cases even better than similar U.S. equipment. This holds true in air-to-air missiles, where China fields the Thunderbolt family of munitions. The latest Thunderbolt missiles outrange U.S. munitions (mostly the AIM-120D) by at least 100 miles. This is absolutely unacceptable, and a major failure on the part of U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy acquisitions. The US counter to the Thunderbolt family is the AIM-260 JATM and according to Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, this weapon will only “hopefully” enter production this year (2023).

In the above image, the red dot represents a Chinese J-20 fighter with the latest Thunderbolt air-to-air missiles. The Blue dot represents an F-35A armed with AIM-120D air-to-air missiles. The shaded boxes represent the estimated max range of each fighter’s missiles.

Many observers are blind to the fact that the U.S. may not be able to simply apply resources and “catch up” to China in the missile gap. Chinese scientists are at least two decades down the path of creating exquisite missile systems and have built up strong institutional and industrial base advantages. Recent U.S. attempts to change the balance of power in the missile domain have failed, again and again. Within only the past 18 months, there have been four failed hypersonic missile tests of Army and Navy systems. Hopefully U.S. development of better air-to-air missiles will not be quite as challenging.

Putting the above issue aside, the U.S. likely does not have enough of the currently fielded munitions on hand to fight China tonight. Putting further strain on U.S. magazine depth will be a surge in the global demand signal for U.S. munitions amongst Washington’s allies and partners including Ukraine and Israel.

Whether the U.S. can catch up in air-to-air missile development and magazine depth is still unknown. This is a significant planning factor which indicates that the U.S. will need more, not less fighter airframes if China retains key missile advantages at least until 2027, which seems likely.

Disadvantage - 5th Gen Readiness & Maintenance

Across all services, aircraft mission capability rates are at their lowest levels in recent history. In March of 2023, the F-35 mission capability rate dipped to 55%, and when combined with F-22s, this meant that only half of the 5th generation fleet was mission capable. This is a massive problem. Considering Chinese cyber attacks or disrupted maintenance on the F-35 fleet during pre-conflict preparations, U.S. commanders may be left with very few 5th generation fighters to actually stop a Chinese rapid invasion scenario. Obviously 50% is a catastrophic number, and one can only hope that mission capable rates will climb in the future.

This extreme reduction in aircraft on hand (aircraft that are combat-coded and mission-capable) argues for a significant increase in the F-35 fleet, as well as an intensive effort to transform the fleet’s endemic maintenance woes. If 40% of the 5th Gen fleet is grounded during an emergency, this leaves the U.S. particularly flat-footed because China is the attacker. China gets to pick the time of an attack and can achieve a higher level of aircraft readiness in anticipation of firing the first shot.

A crucial component of U.S. air combat forces’ advantage lies in stealth/low observable technology. This technology is unusually reliant on U.S. maintenance crew’s capability and capacity to keep the technology “running.” Modern stealth relies on extremely advanced radar absorbent material (RAM) which must be applied to airframes laboriously by hand. Maintainers are required to meticulously apply and inspect these RAM coatings in order to achieve maximum “stealth” on every airframe.

Unfortunately, when fighting China, U.S. air combat forces in the Air Force, Navy, and Marines plan on operating disaggregated from small bases and carriers throughout the first island chain region. Maintenance personnel will be highly challenged in time, resources, equipment, and centralized expertise to maintain the RAM coating on U.S. airframes. This means one of the U.S.’ biggest advantages in air combat could degrade rapidly during a fight with China.

Where Are We Today?

China is beginning to surpass the U.S. this year (2023) in terms of 5th generation fighter production directly supporting domestic military requirements. China’s 5th gen fighter is the Chengdu J-20 Mighty Dragon. Chengdu Aerospace Corporation is currently manufacturing roughly 100 finished J-20s a year, with an expansion expected every year. The U.S. purchases only about 83 F-35s a year. In recent years, Lockheed has manufactured more than 83 F-35s a year, and wants to get to 125 aircraft by 2025. The excess aircraft are destined for F-35 program partners based mostly in Europe.

Even considering the construction of coalition aircraft, the Chinese defense industrial base or “plant” is on the verge of exceeding American capacity. This situation is unique and has never happened in modern war or peace. National leadership must have the vision to see that this is quite a foreboding sign.

During WWII, U.S. fighting platforms were sometimes the all-around best of their time, like the P-51 Mustang fighter or the Essex-class carrier. However, many times they weren’t, like the U.S. M4 Sherman tank. In cases where American equipment was inferior, the U.S. relied on massive quantities produced at the correct peak operational intensities to catch up with the Axis powers.

Hopefully the F-35 will be more like the P-51 than the M4 Sherman. However, we lack the ability to know this presently. The U.S. should maintain a more comfortable margin of platforms to ensure a defense industrial base capable of rearming to produce the levels of platforms required for battlefield success. Unfortunately, the DoD has been charging in the opposite direction:

Regardless of what the DoD thinks about procurement or a limited budget, more F-35s are required. If it is going to take 27 years to design a new fighter (or even 10 years), then this is the workhorse model Washington is stuck with for the foreseeable future. The F-35 has the best mix of capability, affordability, technology maturation, proliferation, and a hot assembly line to boot. There is no other option given current funding levels

NGAD and F-15EX are Not Options

At roughly $300 million per copy, the NGAD will be four times as expensive as an F-35. Each F-35 has only reduced drastically in cost because of the large number of platforms ordered by the international partners involved. NGAD will be unable to achieve such economy of scale since international partners will not be invited into the highly classified project (much like the F-22). The NGAD program is critical to push fighter technology to the next level, but for the foreseeable future it will be a niche capability which still relies on the F-35 as the workhorse of the fleet.

While the NGAD program has its warts, it is still likely to mature into the best fighter in the world and the first 6th gen aircraft. The F-15EX program is extremely troubled from a philosophical perspective. The acquisition of the F-15EX was done for legitimate and sensible reasons.

First, there is a production limit on how many F-35s can be manufactured per year given current levels of F-35 program funding and investment into the industrial base. Second, the limited munitions capacity of the F-35 led to the perceived need for a “missile truck” aircraft. Third, the low readiness of 5th gen aircraft combined with the advanced age and weak airframes of the current F-15 fleet is also leading to a gap the F-15EX hopes to fill.

Yet the F-15EX 4+ gen fighter is more expensive per copy than an F-35A 5th gen stealth fighter. The F-15 is fundamentally late 1960s technology. The decision on the part of the U.S. Air Force to put American pilots into what qualifies as an antique rebuild aircraft is highly questionable considering China’s radar and sensor capability.

What Does Right Look Like? Ramp Up the Defense Industrial Base

If war with China came to pass, the fate of the republic hangs in the balance of two separate, but related, short and sharp platform wars conducted in the sea and air domains. Many of the problems discussed in this memo can be binned into two problem sets. First, an anemic defense industrial base (DIB) and second, a lack of capacity in military units that do the actual fighting.

A larger DIB is required. During WWII, U.S. rearmament began in 1939 and took a full 3 years to ramp up. This was a breathtaking stroke of luck, as the Pearl Harbor attack occurred in the last month of 1941. Just at the same time that Washington was drawn into the war, US national wartime industrial production was hitting stride. In four years, American industrial production, already the world's largest, doubled in size.

This is an awe-inspiring and undersung feat. By 1944, Ford Motor Company had a new B-24 Liberator long-range bomber (containing 1,550,000 parts) coming off the assembly line every 63 minutes, around the clock, seven days a week. While it is common knowledge to our readers that the US is no longer the sole global industrial center of gravity:

U.S. manufacturing and the DIB deserve more thoughtful investment. With a larger and more capable DIB, the F-15EX would not be an attractive choice since it would be relatively easy to simply purchase more F-35s. American hypersonic tests would have higher chances of avoiding abject failure. U.S. combat aircraft fleets would have the capability to reconstitute quickly if Washington suffered heavily at the hands of a Chinese surprise attack at the outset of war. Aircraft readiness would be higher since replacement parts would be cheaper and more widely available. U.S. pilots wouldn’t have to worry about going dry on munitions in the middle of an air war.

Investments in the defense industrial base (which includes plant, workers, and capital) are required. This does not mean that Vermilion is currently proposing U.S. rearmament. Dedicating a significantly larger portion of the U.S. economy to government spending today would adversely affect U.S. economic growth in the future, another key critical dimension of conflict with China. The key is to time U.S. investments wisely.

Sometime in the neighborhood of 2027/28 (more likely 2030) is the earliest possible date that Beijing could initiate a war of choice against Taiwan. Taking the WWII historical example of a three year requirement to attain wartime industrialization, 2025/26 is the earliest window it makes sense for the U.S. to rearm. Even then, it is unlikely that Beijing will show its cards enough by 2025 to force U.S. rearmament.

This means an industrial ramp up, but not rearmament is prudent. Investments in the DIB today pay future dividends. For just one example related to this report, a portion of F-22 manufacturing lines were cannibalized to form the basis of the current F-35 plant.

What Does Right Look Like? Increase Force Structure

Force structure are those units of the military that have combat tasks. Current (2023) U.S. military force structure is the smallest it has been in nearly a century. The reality is that the U.S. currently fields a tiny, expensive military force which is inadequate to the global threat environment and fueling the slow deterioration of deterrence.

The US must think creatively to field fighting units cost effectively and increase U.S. capacity for war. A tried and true method for fielding cost effective combat units is to place them within the National Guard and reserve. In terms of airpower, aircraft squadrons can be placed into these components so that personnel are only paid on a drilling schedule. Theoretically more pilots could be trained on the same aircraft due to the part-time nature of national guard / reserve training.

No matter U.S. qualitative edge, quantity will be required in a fight with China. U.S. military force structure during the Cold War was instructive:

These numbers equal a 1987 FLCAI of 4,899 compared to 34% lower 2023 FLCAI of 3,200.

Relevant Topics Not Discussed In-Depth:

Bombers, which will also affect the air balance.

The strengths and weaknesses of U.S. and Chinese radar systems.

The differences between Fighter jets and Attack jets.

The circuitous military aircraft supply chain.

Glaring problems in the U.S. military acquisitions process, the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (JCIDS).

American and Chinese land-based missiles.

American and Chinese warships.