The Wicker Revolution

Revolutionizing the DoD Acquisition Process

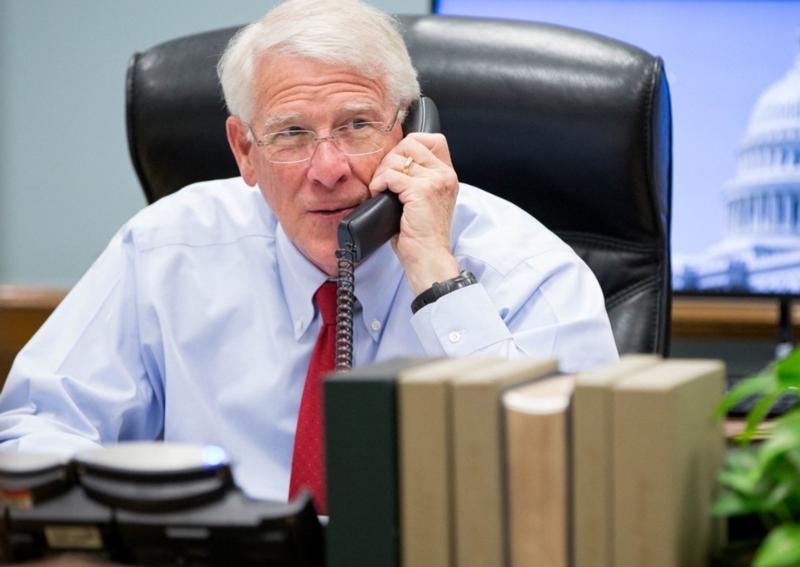

Senator Roger Wicker and staff have suggested a number of serious and thoughtful reforms to the DoD acquisition process. It is clear that Senator Wicker and his team have taken the time to understand the key issues, apply prudent thought to serious solutions, and discuss options broadly with many different stakeholders. Kudos to the office for doing such a competent job.

If any of the staff are reading this, we would like to support your work on acquisition reform, please contact us. We already support other Senate offices on issues of military importance.

It has become fashionable to offer public critiques of the DoD acquisitions system. It is crystal clear that while these other commenters are talented, they lack the depth of understanding of the current system required to reform it. Additionally, we should be wary when those who stand to financially gain are the ones advocating for specific reforms.

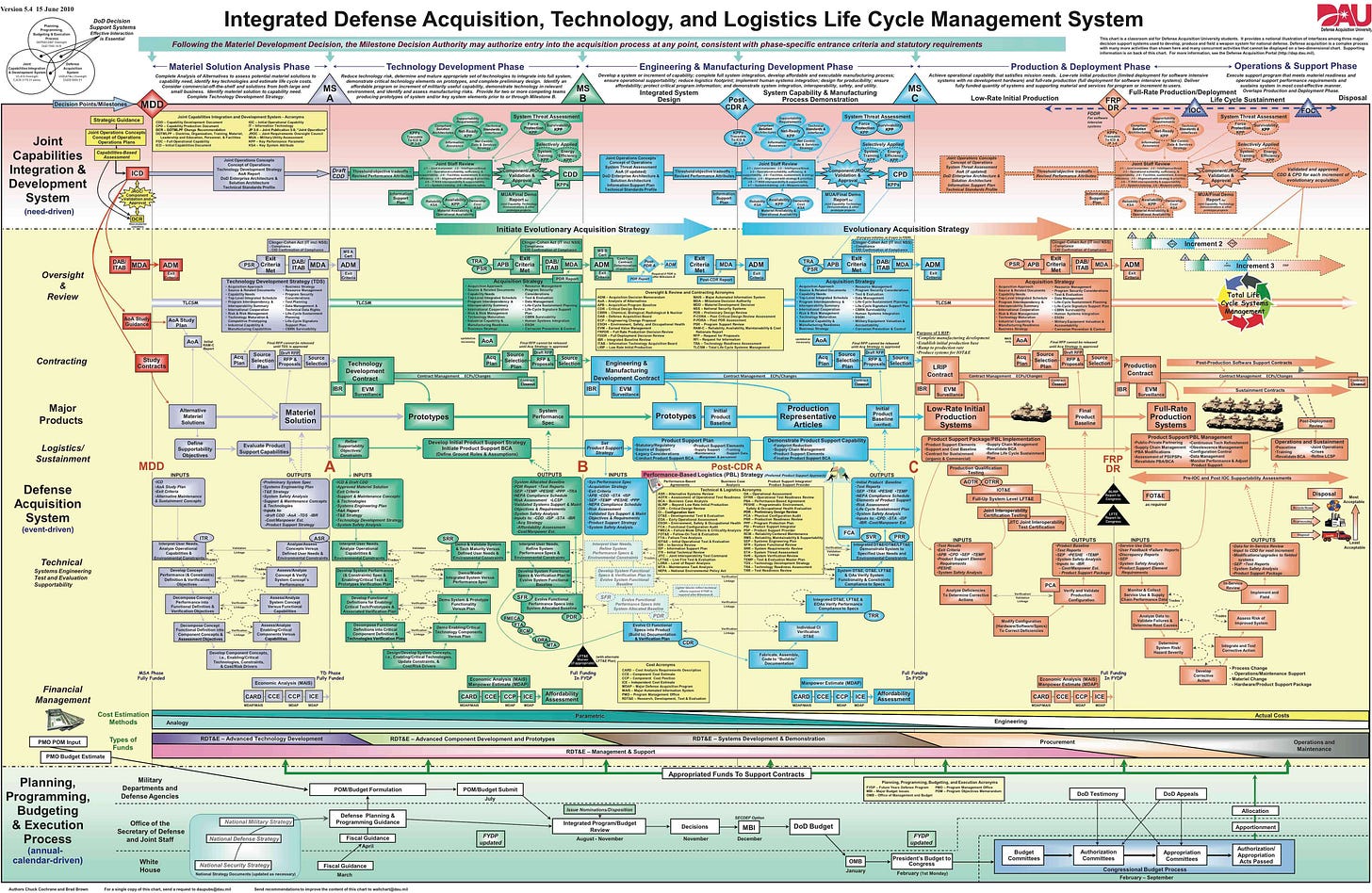

Before we jump into a discussion of Senator Wicker’s recommendations, it is important to get at least a brief understanding of how the acquisition community works. There are three important teams in the acquisition community, forming the three legs of the acquisition stool. The requirements team, the budgeting team, and the program executive office teams.

Warning: This is an article for those truly interested in DoD acquisition reform. The content deals with internal bureaucratic policy, not the most compelling of subjects. Unfortunately, these internal policies have major impacts on how the US fights and the readiness of the US military. As they say, war is boring.

Requirements Team

The first is the requirements team, led by Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Chris Grady, the Navy’s current Old Salt. Admiral Grady chairs the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC).

The JROC brings all the military services together and validates requirements documents for all major DoD programs. Lesser programs can be validated by service-level requirements oversight councils. All requirements documents are meant to outline the specific attributes a DoD capability needs to have.

A requirement is a written description of a capability. A good requirement is:

Clear: the audience reading the requirement, regardless of service, uniformed status, or echelon, understands what the requirement calls for.

Feasible: An industry partner has to be able to produce or research how to produce this capability. If they currently are unable, RDT&E (discussed below) funds will be required to bring about a new capability.

Measurable: The requirement can easily be used as a metric for the DoD operational test & evaluation (OT&E) team to measure performance in real world experiments.

Traceable: Every requirement must be traceable back to the entity that requested it. For example, who asked for longer range artillery? Was it the operating forces? A combatant commander? Was it somebody within the requirements community? Did it come from the Defense Planning Guidance (DPG)?

Budget Team + PPBE Workforce

The budget team is the second leg of the stool. Led by the Honorable Mike McCord, Undersecretary of Defense (Comptroller)/CFO or USD(C), the budget workforce leads the B in the PPBE (Planning, Programming, Budgeting, Execution) process. PPBE is how the DoD, in lockstep and with accountability, turns taxpayer dollars into military capabilities.

The budget team takes guidance from the Undersecretary of Defense Policy or USD(P) in the planning phase of PPBE. The acting USD(P) is Amanda J. Dory and the incoming USD(P) is Bridge Colby. This position creates the national military strategy (nestled in between the President’s national security strategy and the Joint Chiefs’ national defense strategy) and provides policy guidance in a document known as the Defense Planning Guidance (DPG). In most years, the DoD issues the DPG to the military services by April.

The budget team also takes guidance from the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE). CAPE takes guidance from USD(P)’s DPG and in turn, gives guidance to the services on dividing limited resources into the most critical programs.

The services’ output are their Program Objective Memorandums (POMs), which CAPE validates. The POMs are services’ requests to modify what money goes to what programs and the division of colors of money within a program.

The colors of money are meant to track and control a program’s lifecycle. Taxpayer dollars given to DoD acquisitions are not fungible. Each dollar comes with a legally confined set of uses. These uses are:

Research, Development, Test, & Evaluation (RDT&E): The research dollars to explore new capabilities.

Procurement: The purchasing dollars to buy new systems and modify old ones.

Operations & Maintenance (O&M): Funds for military operations, military training, headquarters operations, travel, education, recruiting, depot level maintenance of equipment, civilian salaries, etc.

Military Personnel (MILPERS): Active duty and National Guard salary, permanent change of duty station costs, basic allowance for housing, basic allowance for subsistence, etc.

Military Construction (MILCON): Investment dollars to fund the construction of bases and facilities across the globe.

Once in receipt of 1) a validated requirements document, 2) USD(P)’s DPG, and 3) the service’s CAPE-validated POMs, the budget team does the work of creating an actual military budget (the fabled BES, or Budget Estimate Submission). This BES along with a DoD POM (which deconflicts the service POMs) are sent to POTUS and Congress, for those bodies to modify and approve.

Once military funding is finally approved, the budget team can then begin moving new taxpayer dollars received from Congress across DoD into the correct programs and in the correct colors.

This process updates and creates the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). The FYDP is DoD’s master plan for prioritized allocation and execution of funds across five years, somewhat similar to the classic Soviet and current CCP “5 year plans.”

Program Executive Office (PEO) Teams

The third team consists of the program executive offices (PEOs) led by the Honorable Dr. William LaPlante, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment or USD(A&S). The PEOs work with industry to actually build military equipment in accordance with validated requirements and funds allocated during the PPBE process.

For example, the Navy runs PEO Ships, which “manages the design and construction of all destroyers, amphibious ships and craft, auxiliary ships, special mission ships, sealift ships and support ships.”

Navy’s PEO Ships needs two inputs before it begins managing a program: 1) validated requirements documents for new ships from the requirements team/JROC and 2) funds across the colors of money from the budget team. Once these are received, PEO Ships then works with industry (in the case of ships, usually Huntington Ingalls Industries, General Dynamics National Steel and Shipbuilding Company, or RTX) to begin work on producing a new ship at the pace dictated by the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). The PEO will quarterback this effort.

For another example, the Army runs PEO Soldier. This office “delivers 130 programs of record and 253 products and non-programs of record, such as essential capabilities from body armor, helmets, sensors and lasers [to weapons systems].”

PEO Soldier has four major programs below it, one being Program Manager Soldier Lethality (PM SL). PM SL has a number of product managers, one being Product Manager Soldier Weapons (PdM SW). It is the PdM SW that is in charge of managing the production of the Army’s next-generation rifle, the XM-7 Spear.

Enter the Wicker Report

With an understanding of the current structure, we can now begin to discuss Senator Wicker’s reforms, which we have summarized and simplified below.

Cut Red Tape

1) Reduce requirements documents to a few pages.

Nearly every platform and piece of equipment the DoD purchases is covered by a requirements document. This document covers in specific detail the exact capabilities a piece of equipment must have. For example, a rifle should be able to operate within a certain temperature range, operate ambidextrously, fire a certain cartridge, at a certain muzzle velocity, to a certain distance, to a specific accuracy, etc.

While the intent behind the requirements document has some logic, the process has simply grown far too burdensome and bureaucratic. The number of requirements documents has proliferated. Creating, modifying, and deleting requirements from a life cycle of authorized requirements documents takes months and even years, along with varying layers of bureaucratic approval.

These documents include the Initial Capabilities Document [ICD], Capabilities Development Document [CDD], Capabilities Production Document [CPD], Requirements Definition Package [RDP], Urgent Operational Need (UON), Joint Emergent Operational Need (JEON), and Joint Urgent Operational Need (JUON).

Each of the above documents (particularly the ICD, CDD, and CPD) are supposed to be limited in length to around 35 to 45 pages. While many programs meet this criteria, there are a few larger programs that routinely bust the page limits either through simply ignoring the rules (a number of DoDI 5000 series documents) or through other means.

A validated CDD can require more than two years to produce. Many DoD civilians consider writing requirements documents so onerous and time-consuming, that it is common to hire teams of contractors to write and be responsible for an office’s set of requirements documents.

Senator Wicker wisely contrasts the current unmanageable approach with the requirements document for the Army’s first fixed wing aircraft, issued in 1908. The document fits onto a single page.

Real caps must be put into place. The first step of the bureaucracy after a page limit is adopted is that the bureaucracy will ignore it until ordered to pay attention to orders. Then, the bureaucracy will simply create a 200 page internal document to “cross-walk” the requirements from the official document to the internal document. Effective leadership is required to reign in this runaway process.

Increase Innovation & Competition

2) Suspend Milestone A

First, what the hell are milestones? Most mature defense programs with requirements documents have gone through the three milestone decisions outlined below.

Milestone A is essentially a decision which recognizes that most of the foundational theory work for a program has been completed (capabilities-based analysis [CBA], analysis of alternatives, and an initial capabilities document [ICD]). With this work completed, the program can begin leaving the pages of a Word Doc and enter a form of constrained experimentation called the technology maturation and risk reduction (TMRR) phase.

Milestone B occurs once the program has had a successful TMRR phase and it appears the capability is feasible to produce and there is space in the budget. The program then enters the engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) phase, where the entire system is developed as a whole, real platform.

Milestone C occurs at the end of a successful EMD phase, where the first workable version of the system is eventually put into full rate production to fill out the total number (called the approved acquisition objective [AAO]) required by DoD.

Senator Wicker advocates for removing Milestone A because in current practice, this milestone prevents real experimentation. Too many requirements and theorycraft are stuffed up front, constraining experimentation.

The root of the problem is one of the first steps; the capability based analysis (CBA). Too many CBA meetings are BOGSAT: a bunch of guys sitting and talking.

The value of Milestone A is then directly related to the value of the CBA and follow-on documents like the ICD. Who showed up to the CBA? Who had a more forceful personality or an organizational axe to grind? Is the person writing the ICD an expert on the technology they’re trying to develop? In the current system, these are all treated as bureaucratic problems, not acquisition problems.

To make matters worse, it is too often the case that ICD’s are written with specific solutions or industry partners in mind. By rigging the requirements, DoD prevents true experimentation and exploration of future capabilities.

Senator Wicker is probably right in suggesting a total delete of Milestone A. The decision points surrounding Milestone A would devolve to the program executive office (PEO, the third team) instead of the joint services or Congress.

3) Multiple Program Managers Under a Single Program Executive Office (PEO)

Senator Wicker and team believe the traditional system requires a tweak: placing multiple duplicative program managers under a single PEO in order to create a “defense market” around a certain capability. This would create beneficial competition incentives.

Recalling our US Army example above, one of the Army’s PEOs is PEO Soldier. This PEO runs numerous programs which provide infantry-type capabilities.

Under Senator Wicker’s reforms, PEO Soldier would be able to increase their manpower and funding in order to field two programs for a single capability. For example, PEO Soldier could field Program Soldier Lethality I (PM SL-I) and Program Soldier Lethality II (PM SL-II). This way each program manager could decide to compete to provide the Army’s next generation service rifle.

This would be a much higher quality competition than simply downselecting from a small number of major defense firms in a short period of time, with all firms bidding to be the sole supplier for a single capability. This gives the executive of PEO Soldier more leverage and real options choosing between two service rifle programs.

Or, the PM SL I and II leaders may actually not compete. Maybe PM SL I thinks a new rifle is key to soldier lethality, while PM SL II thinks it would actually be a different capability and not just a rifle. Again, this gives the executive of PEO Soldier more innovative options.

4) Allow program managers to update requirements based on experimentation

Senator Wicker also wants to give the program managers the ability to update their own requirements based on experimentation. This would allow PEO SL I and PEO SL II the opportunity to bypass the requirements workforce and the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) when updating requirements based on real world experiments.

This single change would save months and potentially years of time waiting for approvals, but there must be some kind of “pulse check” or “requirements gate” to get wider DoD community approval of the updated requirements. Perhaps end users could execute these checks, since they are best positioned to understand what is useful.

5) Increase Use of the Software Acquisition Pathway

Within the current requirements process (JCIDS), there exists a path to create streamlined and simpler requirements documents for software-centric capabilities. At one point, this was called the IT Box Construct. However, these methods are rarely internally approved since they give significant freedom of action to the program manager. This should change.

6) Make Consumption-Based Contracts

Institute consumption-based solutions as a permanent model. Today, many businesses (especially software) sell their products as a constantly upgraded service, not as a single capability that the government purchases and then owns and operates independently of the developer.

This has traditionally been a friction point between DoD and Palantir. Palantir’s analytics service requires costly ongoing support in the form of forward deployed engineers and add-on server space that add serious costs to the program. However, these costs are what made Palantir so much better than existing DoD analysis software.

While the users of Palantir understood this, the acquisitions workforce did not. This is primarily because the acquisition workforce would never actually use Palantir; they were only in charge of buying it.

Therefore, the teams in charge of acquiring Palantir were very ambivalent about paying for what were seen as “extras.” The acquisition team would prefer to simply buy a locked down version of the software and own it in perpetuity. From the perspective of the acquisition workforce, Palantir’s quality was seen as a costly and unnecessary add-on. From the perspective of the end user, it was seen as a core capability and unique selling point.

Consumption-based contracts could be used to streamline DoD’s software purchases. Creative application could also support streamlined purchase of advanced munitions that require software updates or tactical drones that require software updates to survive shifting EW conditions.

7) Provide Flexible Contract Pricing

Currently, many government employees who oversee contracts (contracting officers) utilize cost-based pricing. This means they look at a program’s costs and add 10% to calculate a “reasonable profit,” whatever that means. “Reasonable profit” is used as the bound of what a private company can charge the government.

This method destroys any incentive for defense firms to cut costs, since becoming more efficient and cutting costs would reduce the simple 10% profit calculation. DoD government acquisition leaders should be enabled to use a variety of methods (including cost-per military effect analysis) to justify from the government’s perspective what prices private firms may or may not “reasonably” charge. Traditional contracts should still have the option of using cost-based pricing for large projects trying to develop the most cutting-edge capabilities.

8) Empower the acquisitions workforce by delegating significant decision making authority to the PEO, transforming it into a PAE

As we discussed in the introduction to this article, the acquisition workforce is separated into three legs of a stool: requirements, budgeting, and the PEOs. The PEO is the main stakeholder responsible for the cost, schedule, and performance of any particular program. However, the PEO has little ability to affect the process outside of his small office.

The requirements owners do not take marching orders from the PEO. These stakeholders define the required capability (eg, an aircraft that flies for how long and how high) the PEO should seek to field. The budgeteers work for separate parts of the bureaucracy and are seldom seen working closely with their counterparts outside of spreadsheet wrangling.

While these are the three big legs, there are numerous other stakeholders. For example, end users (the soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and guardians that actually use the equipment) should have significant influence over the PEO. Congress obviously plays an outsize role. Industry is hugely influential as the defense primes produce much of DoD’s equipment. The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) as well as other Pentagon offices also exert tremendous influence.

There are simply too many stakeholders to maintain a functional process. Senator Wicker wants to change this by folding most of the required support staff like requirements owners, budgeteers, system developer representatives, end user input staff, and others under the direct responsibility of the PEO. Therefore, the PEO would be a single decision center responsible for the success of any given set of programs.

Senator Wicker goes farther and suggests that PEOs should be upgraded to portfolio acquisition executives (PAEs). The individuals in charge of the PAEs would be drawn from general officers / flag officers (GOFOs) and the DoD civilian senior executive service (SES). These are the most seasoned leaders the DoD has on hand.

These changes would allow the PAEs to define, prioritize, and refine their own requirements. Approvals from the service staffs would only come into formal effect once a program hit a Milestone B decision (see our discussion above on Milestone A).

Senator Wicker also suggests that the powerful but slow Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) be downgraded to an advisory board function which makes suggestions and focuses on deconfliction of programs and portfolios.

Currently, the JROC acts as an approval committee of powerful GOFOs from each service that decide what programs are started, and what programs enter which Milestone decisions. The functional result is micromanagement and horse trading between the services.

9) Increase Commercial Solutions Openings (CSOs)

The DoD should be purchasing commercial supplies instead of specialty supplies whenever possible. Simple solution. CSOs should be a standard approach from the start instead of defaulting to a DoD-centric model.

Defense Budgeting Reform

The PPBE process is how the DoD methodically allocates and expends funds across all services and all activities in lock step.

The system does work and gives a very high level of traceability for each defense dollar allocated and expended. The responsibility to Congress for every taxpayer dollar expended on systems is high (not manpower).

However, the process is too slow, non-expert consensus based, and doesn’t reward initiative or innovation in execution.

10) Move Senior Oversight From the Program to the Portfolio Level

Most importantly, the PPBE process manages DoD activities at high levels of specificity at the program level. For example, in the 1950s before PPBE was adopted, the US Navy had a single line item for “naval ships.” This line item was the wallet for all naval shipbuilding, including surface vessels, submarines, amphibious ships, and carriers.

Navy leaders had considerable leeway, shorter decision chains, and more delegated authority in making changes to the Navy ship mix. For example, “in 1961, the Navy could initiate the new start of five fleet ballistic missile submarines under its own authority.”

Today, that would be a legislative decision requiring Congressional consent along with numerous layers of Joint, Departmental, and civilian concurrence. This is because PPBE manages DoD platforms at the program level, not the portfolio level. There is a separate line item for each type and variant of vessel the Navy operates, and Congress is expected to provide oversight at this level.

PPBE also requires congressional consent in moving money between programs (e.g. from the Virginia-class submarines program to the Columbia-class submarine program because the former program had extra funds at the closing of the fiscal year and the latter program needed a top up), or to even start a new program.

If everything becomes reportable directly to Congress, the incentive structure becomes highly risk averse. Everything and anything could get a senior officer sidelined or fired.

An analogy from the talented Senator Wicker and staff:

“[Imagine] a household budgeting every $15 it spends three years in advance and requiring approval from the bank to move $5 dollars from buying hamburgers to hot dogs. This is no way to run a household, let alone the Department of Defense. A budget category of “groceries” makes more sense than separate budget lines for hamburgers, hotdogs, steak, chicken, salmon, and so forth.”

11) Delegate Authority to Change Colors of Money

Senator Wicker suggests scrapping the need to ask for permission to move colors of money.

Instead, the line item should be consolidated into something like “PAE Armored Vehicles,” where the acquisition executive retains final authority to shift colors of money across tank/armored vehicle programs. This makes sense.

12) Institute PPBE Reform

Of course, the entire DoD PPBE cycle may need reform. This is a separate topic that can be explored through existing work already done by the Senate.

Wicker’s Tradeoffs

While we're huge fans of the above reforms, they still come with tradeoffs.

1) These reforms place far more trust at the GOFO/SES level to execute DoD’s acquisitions. Increasing innovation and the process speed can only happen if Congress limits its own oversight.

This weakness can be ameliorated by the general board concept. This would bring in older senior officials without a career to worry about in order to provide the best unbiased advice. This general board concept could be used to reinforce the existing JROC (discussed above), which could give broader advice to Congress on program deconfliction and management.

Since Senator Wicker suggests upgrading the PEOs to PAEs with more senior personnel leading major efforts, there is no reason to limit senior participation to such a narrow career field. Bringing in outside blood at the top level of the PAEs could bring huge benefits to the DoD. For example, there is no reason why someone like Fred Smith or Jack Dorsey couldn’t rotate in as a PAE executive.

With less congressional accountability, there may also be reasons to strengthen the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and reform the DoD Congressional Liaison staffing model.

2) Currently, the three legs of DoD acquisition are separated in order to prevent conflicts of Interest. More acquisitions Staff Judge Advocate (SJA) staffing will be required to keep acquisitions leaders out of boiling water.

Conclusion

As the Trump administration enters office, there is an unusual amount of public attention devoted to DoD acquisitions. This is usually such an esoteric topic that it gets virtually no bandwidth in the public consciousness, let alone the expert community. Now is the time to reform.