The Mysterious Murder of Jim Li

A loss for the United States

This article is excerpted from the NY Mag article “The Radical, Lonely, Suddenly Shocking Life of Wang Juntao” written by Christopher Beam. Please give it a read.

Jim—who then went by his Chinese name, Jinjin — came from a family loyal to the Communists. Before they took over in 1949, his father had been a tailor. By the time Jim was born, in 1955, he was a teacher at the police academy of Hubei province on his way to becoming a department head. For a time, it looked like Jim would follow in his father’s footsteps. He enlisted in the army at 15, serving as a telegraph operator, and later joined the Wuhan police department, assigned to catch pickpockets on city buses. But his politics changed at the Hubei College of Business and Finance, where he studied law and wrote a thesis on the U.S. Constitution. A professor who worked on China’s 1982 Constitution — which introduced reforms like term limits—showed him that changing the system was possible. Jim returned to Wuhan to teach.

Jim then pursued a doctorate in law at Peking University, where he was elected president of the graduate-student body, a position that put him on the fast track to Party leadership. “If he had not joined the Tiananmen movement in 1989, his future would have been limitless,” a fellow activist told me.

In April 1989, after the death of Hu Yaobang, a liberal Party elder who had championed many of the country’s free-market reforms, students flooded into Tiananmen Square to demand wholesale change: accountability, due process, democracy. The protests lasted for weeks. Meanwhile, Jim was working to organize a union called the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation. Aside from a group that had briefly operated in Taiyuan years before, it was the first independent labor organization in the country. “Our old unions were welfare organizations,” Jim told a young New York Times reporter named Nicholas Kristof. “But now we will create a union that is not a welfare organization but one concerned with workers’ rights.” Jim’s alliance scared Beijing’s Party elite: That same month in Poland, a similar coalition had successfully negotiated for reforms with the Communist government.

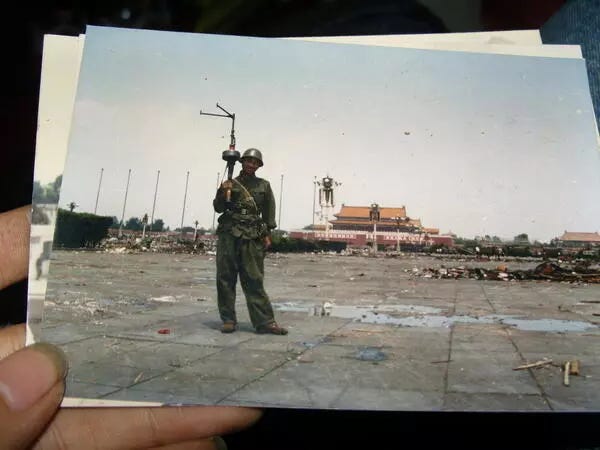

On June 3, Jim got on his bike and headed toward Tiananmen for another night of protests. On the way, he heard gunshots and saw students running in the opposite direction, some injured and bloodied. The Chinese military had opened fire on protesters, killing hundreds. Jim turned back. A memoir he wrote in 2009 offers no further details.

After the massacre, the Communist Party rounded up as many protesters as it could. Many escaped the country, but thousands were arrested and an unknown number were executed. Jim was caught after a few days and sent to prison in Beijing on charges of “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement.” In 1991, after 681 days behind bars, he was released when the government decided not to prosecute. He sold real estate and taught at small schools for two years, until the authorities allowed him to leave the country, along with his wife and son, and attend Columbia University.

At Columbia, Jim found that the celebrity of his Tiananmen activism afforded him no great status. He and his family lived in an apartment near the university, and to make rent he delivered food for a Peking-duck restaurant. Later, they moved to the Midwest so Jim could get two degrees (a master’s of law and a doctorate) at the University of Wisconsin; eventually they settled in Queens, where they crammed into a one-bedroom apartment, sleeping on a borrowed mattress.

When Jim and his friend Wang Juntao, a fellow dissident who had been jailed in Beijing following the events of Tiananmen, finally reunited in New York, they picked up their boozy bull sessions, conspiring to influence Chinese politics from afar. In their 30s, they lobbied members of Congress to support fledgling pro-democracy groups in China and to pass resolutions promoting human rights there.

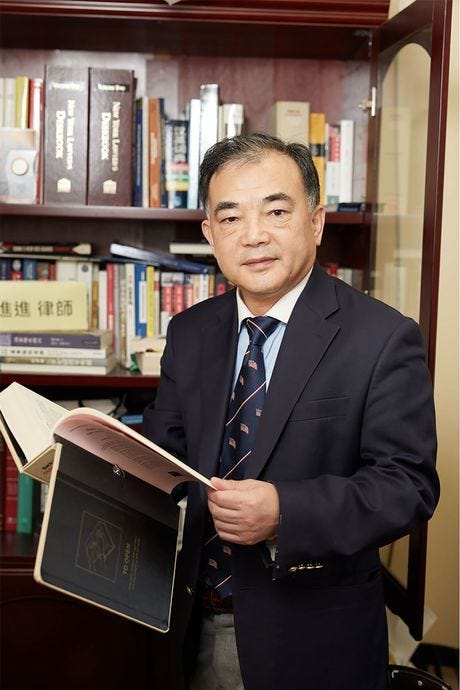

As time went on, Jim remained deeply opposed to the Communists. (Juntao recalls that Jim once saw an old couple dancing to a traditional Communist song in Chinatown and yelled, “Go back to China, fuck you!”) But his true calling had always been the law, not politics. He started a legal practice in Flushing on a shoestring budget and soon developed a reputation as a rigorous attorney specializing in immigration, asylum, and sensitive “Red Notice” cases protecting clients from being extradited to China. But he was a bad businessman, hiring friends and family and taking on too many cases for free. To attract more paying clients, Jim began attending social events hosted by a “hometown committee” — an organization friendly with the Communist Party. When his dissident allies objected, Jim told them, not very convincingly, that he was trying to influence the group’s politics from the inside.

Within a few years, he had saved enough to buy a house in Jericho, Long Island, and had taken up skiing and golf. When his parents immigrated, Jim bought a house for them, too, on a leafy street in Flushing. Jim’s father, bitter that his son’s activism had hurt his career, often warned him not to do anything “against China.” Jim would reply that he was working not against China but against the Communist Party. Either way, Jim grew more moderate as he got older. In 2006, he co-founded the Hu Yaobang & Zhao Ziyang Memorial Foundation, an organization dedicated to persuasion and reform, not revolution.

In January 2022, a 25-year-old named Zhang Xiaoning showed up at Jim’s office and asked for a meeting. She said that she’d been raped by a police officer in Beijing and that when she filed a complaint, the government covered it up and put her in a mental institution. Zhang got out and flew to the U.S. in August 2021. She’d been trying to bring attention to her ordeal, protesting in front of the U.N. and the White House. Now she needed a lawyer to help her apply for political asylum.

Jim was sympathetic but wary. Zhang seemed to have “emotional problems,” he wrote in a memo. But untreated mental-health issues are common in China, and while there were some discrepancies in Zhang’s story — in some paperwork, she complained of “sexual harassment” instead of rape — Jim trusted her. He agreed to take on Zhang’s case for free.

Over the coming weeks, they met several times to work on her asylum application, and Zhang acted more and more strangely, according to Jim’s memo. She asked whether Jim felt guilty about participating in the pro-democracy movement, given the “pain” it had caused his family. The memo goes on to describe Zhang emailing him complaining about other members of the minyun (the movement for democracy in the People’s Republic of China) and calling them dogs; one evening, according to the memo, she phoned Jim nine times, then sent an email calling him a “loser.”

Zhang was living at a hostel on Kissena Boulevard in Flushing, sharing a room with several other women for around $450 a month, according to a fellow lodger named Victor. She had few possessions — a handful of plastic bags and a coat — and almost no money. She didn’t use her real name when interacting with roommates, instead calling herself “An-An.” Victor heard from the landlord that she was obsessed with Jim Li, showing pictures of the lawyer to her roommates and landlord and saying she was in love and wanted to marry him. (Jim’s first marriage ended in divorce, and he later remarried. I never saw any evidence that he was romantically involved with Zhang.)

On February 18, Zhang told Jim that the rape story was false. She’d heard of such things happening to other women, she said, but it hadn’t happened to her. Jim said he could no longer represent her. Zhang begged him to reconsider. Now that she’d publicly denounced the Communists, she would almost certainly be persecuted if she returned to China. In New York, she’d already been harassed by officials from the Chinese consulate, she said, and back home the Party had been giving her parents trouble. Having fabricated her case to boost her chances of winning asylum, she was now facing deportation — a worst-case scenario.

Zhang returned to Jim’s office repeatedly to try to change his mind. On March 11, she lost her temper and allegedly tried to strangle him. An employee called the police, but when they arrived, Jim asked them to let Zhang go. Later that day, Zhang called Juntao, almost crying, and asked for help. They’d spoken once before, and she knew that he and Jim were close. During an hour-and-a-half-long conversation, Juntao reassured her that she could make amends. All she had to do was bring Jim a dessert and apologize, he said, and the lawyer would come around.

Juntao also suggested that Zhang join a protest he was planning for the next day. In Times Square, they met in person for the first time. Zhang was slight and nervous-looking, with rimless glasses. Wearing a blue face mask, she stood in front of a TKTS sign, raised a fist, and chanted, along with Juntao and a couple dozen others, “Free, free China! Democracy China!” At one point, Zhang removed her mask, exposing her face to the cameras. Juntao took it as a sign of her commitment and felt a surge of pride.

The following Monday, March 14, Juntao was driving when a friend called to say that Jim had been attacked. Juntao pulled into a parking lot and called Jim’s phone. No one answered, so he tried the office. Someone picked up and told him in a shaky voice that Jim was “gone.”

Zhang had shown up at Jim’s building that morning carrying a cake and saying she wanted to apologize — just as Juntao had suggested. Jim invited her into his office. A few minutes later, the secretary heard them arguing and then a shout. She opened the door to discover Jim in his swivel chair, covered in blood, with Zhang standing beside him holding a knife. Another employee charged in and restrained her while the secretary called 911.

Jim was pronounced dead at the hospital. The next day, Zhang was charged with his murder.

On March 16, Juntao visited Jim’s office, taking in the large brown bloodstain on the carpet and laying flowers at a makeshift shrine. Jim’s employees told him they had found a strange clue: a couple of flags Zhang had left behind representing China and the Communist Party.

At almost the same moment, federal prosecutors in Washington held a press conference to announce the arrest of five men on charges of harassing and spying on Chinese dissidents in America. Juntao knew one of them well: Wang Shujun, a kindly historian who served as secretary-general of the foundation Jim had led. According to the Department of Justice, since 2005, Shujun had been collecting intelligence for China’s Ministry of State Security about dissidents in New York — which, if true, would almost certainly have included Jim.

Shujun’s arrest, combined with Zhang’s perp walk and the flags, fueled wild theories about Jim’s death. “When the FBI was about to close the net on Wang Shujun and the foundation, Li Jinjin was suddenly silenced,” one Twitter user wrote in Chinese, referring to Jim by his Chinese name. A local journalist wrote a song speculating about a connection: “They tell the press it’s just a coincidence / But denying the link to the murder makes no sense.”

When I met Juntao for dinner one night in April, he said he’d concluded that Jim was assassinated. “The dissident community has a consensus that this is political murder,” he said. Juntao said he believed the Party eliminated Jim because he was helping the U.S. government expose moles in the minyun.

Video of Zhang’s arrest.

Vermilion Note: It is unknown whether or not this murder was motivated by ideology or was the result of mental illness. What can be concluded from Li’s murder and the arrests of Zhang and Wang, is that CCP efforts to silence dissidents within the United States and radicalize pro-CCP individuals are very real problems that must be addressed and countered by Washington. This is one of several instances of recent CCP radicalization that will be highlighted going forward.