Sleepwalking into War: the Folly of Restraint

Vermilion readers, after reviewing a recent article on China, we felt compelled to respond to the article in detail. These arguments are especially pertinent considering the escalatory nature of recent PRC actions within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone, including the ramming of coast guard vessels which occurred in the early morning of 19 August 2024.

The original article is in normal text, with Vermilion responses in block quotes.

Second Thomas Shoal isn’t Worth War with China

Tensions have eased slightly in the South China Sea as Manila and Beijing appear to have come to an agreement on the humanitarian delivery of supplies to the Philippines’ beleaguered outpost, the rusting and rapidly deteriorating remains of a WWII-era warship that was intentionally grounded on Second Thomas Shoal.

First, the author begins the article with an egregiously unacknowledged bias. The Second Thomas Shoal (2TS) is not a “beleaguered outpost,” but in fact part of the Republic of the Philippines. Manila should never have to “come to an agreement” with Beijing over activity within the Philippine’s own jurisdiction.

The UN decided this issue in the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration delivered from a UN court on the basis of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Both the PRC and the Republic of the Philippines are dual-ratified (convention and agreement) parties to UNCLOS.

Paragraphs 381-383 of the UNCLOS decision between PRC and Philippines determine that Second Thomas Shoal (2TS) is a low-tide elevation (LTE). No country can make sovereign claims over an LTE alone. Therefore, 2TS falls under the jurisdiction of the Philippines’ existing exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a 200 nautical mile buffer in which states have special rights. According to paragraph 290, 2TS is only 104 nautical miles from the Philippines’ baseline of Palawan, while it is 616 nautical miles from the PRC’s closest baseline of Dongzhou near Hainan Island.

Regardless, the Tribunal still explored the possibility that Spratly features could theoretically give PRC a claim to 2TS. The Tribunal found that the Spratly region does contain high-tide elevations (HTEs) which could possibly be granted rights.

In paragraph 615, the Tribunal reviewed the evidence and noted the presence of potable water on Itu Aba Island. This water could possibly be combined with rainwater collection to form the basis for sustaining human habitation. But by paragraph 626, the Tribunal has ruled out this small possibility after finding no evidence of anything but transient human movement throughout the history of the Spratly region.

This means the PRC is granted no exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or continental shelf rights from the Spratly Islands. Even if it were, it is actually Taiwan that occupies Itu Aba Island within the Spratly group, not the PRC.

The other HTE features in the Spratly region are rocks, which similarly do not confer EEZ or continental shelf rights.

Setting the above aside, the Tribunal also saw no validity in the larger PRC “nine-dash line” (now ten-dash line) because China (in any of its forms) never established a permanent population within the South China Sea nor established the exclusive use of resources within the South China Sea. These arguments are outlined in paragraph 631.

Manila should not need to “come to an agreement,” as the author writes, to deliver supplies to an LTE which is rightly within the Philippines’ own EEZ. By paragraph 741 of the ruling, it is clear that the decision finds the PRC should show due regard to the Republic of Philippines’ laws when operating in and around 2TS (which falls in the Philippines’ EEZ).

The CCP consistently declares that the PRC has indisputable sovereignty over the Spratly Islands and surrounding areas (including 2TS). This unjustifiable claim is supposed to extend throughout the South China Sea, and the CCP attempts to realize this bogus claim partly by its aggressions against 2TS.

Secondly, while the author mentions the BRP Sierra Madre was intentionally grounded, this certainly pales in comparison to the ongoing militarization of the PRC’s SCS features by any measure, something he notes later in the article.

Finally, as noted in the introduction, tensions have not eased slightly.

To be sure, this new development in the long-running maritime dispute is encouraging. But another crisis could unfortunately be just around the corner as both parties are already arguing about what exactly has been agreed.

China experts should be aware that the CCP rarely, if ever, negotiates in good faith. While there are too many examples to count, one will suffice for this debate. The PRC never actually showed up to the UNCLOS arbitration in 2016 (please check the decision document, early in the document on page i, it displays that no representatives of the PRC ever showed up). Beijing was likely aware that its claims have no merit.

Of course both parties are arguing about the 2TS resupply agreement, in this case the PRC has no valid argument that extends beyond the range of its gunboats.

In June, Chinese Coast Guard personnel assaulted and took control of a small Philippine vessel that was approaching Second Thomas Shoal. Some commentators even called for the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty to be invoked.

It should be clear that the PRC is the escalatory party here, not the Philippines.

With the tenuous situation in Ukraine, ominous signs in the Taiwan Strait, and a tumultuous US election season in full swing, Washington is no doubt loathe to exhibit any hint of weakness.

The US Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense made simultaneous visits to Manila recently, bringing with them a US$500 million aid package and a proposal for enhanced intelligence sharing.

There certainly has been no shortage of US military activity in and around the Philippines in 2024. For example, the US Marine Corps recently flew missions from Luzon with its new F-35B, and the US Army first deployed (albeit temporarily) its first Mid-Range Capability (MRC) missile to the Philippines as well just a couple of months earlier.

Observing such tendencies, it’s worth asking whether or not risking an armed clash with China in the South China Sea genuinely serves US national interests. Many in Washington evince grave concern over “Chinese expansion” and “Beijing’s aggression,” yet such attitudes do not actually conform to the facts of the case.

First, the author is framing the argument to only capture the negative risks of escalation without discussing the reason for the risk - supporting mutual defense treaty allies.

Second, a pattern of Chinese aggression certainly does conform to the facts of the case, but this is better discussed further below in the Vermilion commentary.

On a third (minor) note, the US Army’s Mid-Range Capability (MRC) is now a more mature program known as the Typhon Strategic Mid-Range Fires (SMRF) system. This system is employed by the US Army’s Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF).

It is true that China has built up reef bases in the South China Sea – moving lots of sand and concrete around in the process and ruffling a lot of feathers inside and outside the region during that process.

Nevertheless, it is rarely noted that China has deliberately chosen not to fully exploit that new position “on the chessboard” by placing combat-ready air wings at the extensive new bases.

This is a confused statement, and exposes limited military experience and knowledge of the history of South China Sea disputes. The author suggests that China not placing “combat-ready air wings” signals some type of restraint.

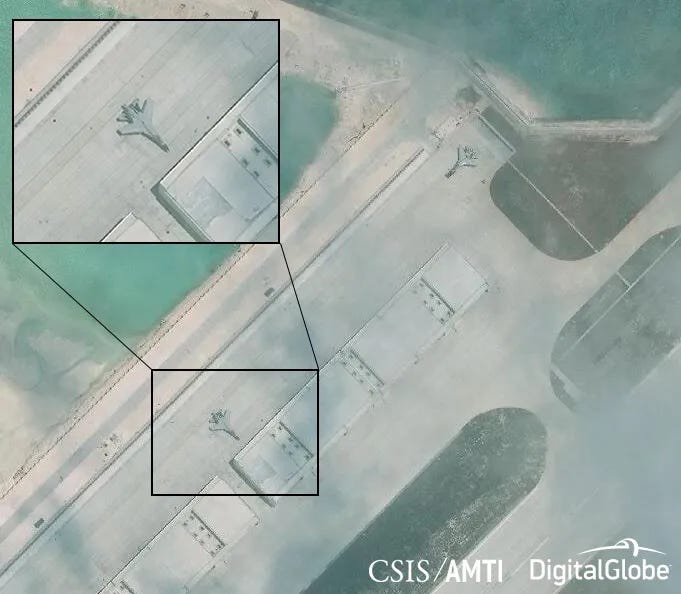

First, the statement is false on technical grounds. Time, time, and time again, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) has operated and based aircraft throughout the South China Sea region. These aircraft include the J-11B fighter, JH-7 attack aircraft, Y-8 transport, and the PLAAF’s largest Y-20 transport. The PLAAF regularly operates various aircraft across PLA South China Sea (SCS) air bases.

As early as 2016, J-11B fighter aircraft were spotted on Woody Island in the Paracel group (imagery above). There is even a Youtube video of what appears to be PLAAF J-11B and JH-7 supposedly training in the Spratly Islands (南沙岛).

Second, aircraft are some of the quickest movers in a military organization. Rebasing aircraft, ground crew, or headquarters units to the SCS takes mere hours. If the CCP decided to move more air capability to the SCS, it would be quite simple considering the already extensive facilities across the SCS air bases.

This is certainly not a clear sign of restraint, just shrewd military posture. In fact, it is the Philippines showing restraint in not militarizing 2TS, only seeking to reinforce the existing vessel structure.

On a third (minor) point, the PLA’s air units are not organized into wings, this is US terminology. The vast majority of PLAAF units are organized into brigades (旅) which report to PLAAF air bases (空基地). Only a few bomber and lift formations retained the regiment (团) reporting to the division (师) echelon. PLAAF divisions then report to the same PLAAF air base (空基地) as a brigade. The PLAAF brigade, division, air base structure does not neatly fit into the US echelonment of squadrons reporting to groups reporting to wings.

Likewise, the choice of resorting frequently to water cannon by the Chinese Coast Guard is not accidental. It’s a conscious choice to pursue Beijing’s objectives without resorting to lethal force – another clear sign of restraint.

The water cannons employed by the Chinese Coast Guard are powerful enough to damage vessels and break glass, as they have done multiple times to Philippine vessels. Whether lethal or not, the tactic is used in an attempt to avoid triggering the US-Philippines mutual defense treaty (MDT).

This is not clearly a sign of restraint (as the author suggests) but simply a peacetime use of military force on the part of the CCP to achieve objectives short of war. The author seems to be desperate to paint the CCP as responsible (or clearly restrained) for causing the exact situation that could lead to the escalation he fears.

Looking at the situation within a larger picture, moreover, one sees that China is not actually blocking or hindering international trade in these crucial sea lanes, nor has it resorted to the large-scale use of force in more than four decades – a remarkable record for a rising great power.

Of course the PRC is not blocking or hindering international trade yet, since a blockade is generally interpreted as an act of war. What nations in the region worry about is the trend line, and Beijing’s ability to control these sea lanes in the future.

The PRC has become a major seapower in only the last decade, a blink of the eye in terms of international power politics. The question in the mind of every leader in the region is why? Why has Beijing built out the world’s largest fleet now? Capitals throughout Asia trust the US with the power and duty of patrolling the sea lanes, not the PRC.

The author is also incorrect when stating that it is remarkable for a rising great power to eschew the large-scale use of force. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1871 and the proclamation of the German Empire, Imperial Germany would not go to war for 43 years until the outbreak of WWII. During those four decades, Imperial Germany would generally have irregular skirmishes in colonial outposts with casualties perhaps counting in the tens.

Similarly, it would be about 20 years between the end of the German Revolution and the establishment of the Weimar Republic in 1919 to the 1939 Nazi German invasion (not annexation) of Czechoslovakia. Interwar Germany was mostly concerned with quelling internal uprisings. It is not remarkable at all for a great power to avoid engagement in costly large-scale wars until the rising national command authority lashes out in aggression.

So, what exactly is China’s game in the South China Sea? Unquestionably, Beijing seeks to protect its own fishing and drilling prerogatives. Still more important are the strategic imperatives to safeguard China’s trading routes, as well as the relatively new basing of the Chinese Navy’s nuclear missile submarines.

First, again, the author makes the claim that the fishing and drilling rights in these regions belong to Beijing, which they certainly do not, as already outlined by Vermilion’s discussion of the 2TS arbitration above.

Second, he writes that the PRC has a strategic imperative to safeguard China’s trading routes - from what exactly? Here, the author can only be making an implied reference to the US Navy cutting off the PRC’s trade routes (the only force with the capability to do so) - why would POTUS order the USN to cut off the PRC? Because of some type of egregious aggressive behavior on the part of Beijing, of course.

The latent ability of the US/Philippines to cut off the PRC from trade likely acts as a brake to PRC adventurism and escalatory action, not an accelerant. The author has confused the cure for the poison.

Since the normalization of relations between the PRC and US, Chinese maritime trade has been protected by the sweat of the US Navy. Beijing has “40 years” of trust built up that Washington will not cut Beijing off from trade - on the implicit promise that Beijing does not start a war. This is a good deal which acts as a stabilizer of US-PRC relations and it is vital that Washington maintains such leverage

Nevertheless, China’s primary motive has been neglected by almost all reporting on the South China Sea issue, regrettably.

A glance at a map reveals that the Philippines is extremely proximate to the sensitive Taiwan Strait. New US basing in its former colony would grant Washington a significantly improved position in the context of a conflict over Taiwan between China and America.

Yet, Manila politics can be quite topsy-turvy and the Philippines Constitution actually forbids foreign basing in the country – a fact little understood by Americans. Given the rather delicate history between Washington and Manila, the basing position is far from secure.

We would suggest that it is actually the author who doesn’t understand the Philippines Constitution. Article XVIII, Section 25, of the Philippines Constitution states that “foreign military bases, troops, or facilities shall not be allowed in the Philippines except under a treaty duly concurred in by the Senate and, when the Congress so requires, ratified by a majority of the votes cast by the people in a national referendum held for that purpose, and recognized as a treaty by the other contracting State.”

The presence of foreign military forces and bases are certainly allowed with the consent of the Philippines' Senate, or if required, a national referendum. Regardless, US military forces can operate in the Philippines on a rotational basis effectively until some future escalation on the part of the PRC induces Manila to seek a permanent US base treaty.

Therefore, the US has been working overtime to secure its “new” foothold in the archipelago by making upgrades to facilities at six different sites, including on Luzon, the island closest to Taiwan.

There are real problems with trying to defend Taiwan, especially considering that China has achieved conventional superiority in the surrounding area and there are considerable nuclear risks too.

It is quite unclear if the PRC has achieved conventional superiority in any domain. The author may be confused about statements such as General Kelley’s in 2022 on the US Air Force losing conventional overmatch against the PLA.

Overmatch is when a force has capabilities or tactics which compel the adversary to cease employing their own capabilities or tactics because doing so leads to defeat for the adversary nearly every time. This is much different than superiority.

As far as nuclear risks, Ukraine has been dragging on for years now with the PRC supporting Moscow and the US supporting Kyiv. Nuclear escalation has not yet raised its ugly head.

But putting such issues aside, The author’s argument is that Washington’s military cooperation with Manila is the true reason behind the PRC taking aggressive action against 2TS. Yet to Filipino ears, this assertion rings false.

Beijing has continued escalation over 2TS consistently, even during the immediately preceding era when Manila attempted to appease Beijing. Under the Duterte administration, the Philippines cast aside its relationship with the US and embraced the PRC. “On [Duterte’s] first trip to Beijing in 2016, he announced it was “time to say goodbye to Washington.”

The Philippines made numerous overtures to the PRC, including a bizarre statement from Duterte himself asserting that neither the Philippines nor the US were able to stop the PRC from militarizing the SCS and that the Philippines would lose a war with the PRC.

Duterte would take other material steps to cozy up to the PRC regime while distancing Manila from Washington, including embracing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as well as icing for an extended period the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) which governs US troop rotations in the Philippines.

Yet for all of the Philippines’ conciliatory outreach, deferent behavior, and quisling approach to the PRC, Beijing was utterly incapable of moderation. Instead, the CCP read these actions as a signal to ratchet up aggression and escalation.

A series of unilateral SCS actions on Beijing’s part in the early 2020s here, here, here, here, and here finally forced Duterte to acknowledge that Manila’s policy of appeasement had failed. Duterte did an about face, and opened to strenghtening the Philippines' relationship with the US.

The most important question the article fails to answer is why the author thinks this time is different? If such an approach simply led to a deteriorating security situation for Manila in the very recent past (dealing with nearly the same set of PRC leaders), there is no reason to believe that unilateral concessions to the PRC would be a successful strategy now versus a few years ago.

Yet, this ultra-dangerous problem at the heart of the contemporary US-China military rivalry seems to be also destabilizing the South China Sea situation now too, as Beijing seeks to demonstrate its displeasure with Manila’s permitting new basing positions to Washington just south of Taiwan.

It is not coincidental that the Philippines’ position at Second Thomas Shoal became a “hot potato” at precisely the same time at which the US started getting much more serious about improving its basing on the northern flank of the Philippine archipelago.

Make no mistake, the US should act to defend the Philippines if that proves necessary. There is a long-running alliance treaty relationship that reflects the very deep cultural-historical relationship that goes back over a century.

At this point, it seems the author is reversing his own argument or at least having second thoughts.

On the other hand, Washington should not embark lightly on risking war with another nuclear power. Common sense dictates that the US should completely rule out any notion of going to war with China over a contested shoal or some angry fishermen.

It should be clear at this point that the issue is not “angry fisherman.” The issue at stake is not even a contested shoal or LTE. The issue at stake is the survival of the rules-based international order which, warts and all, has prevented the outbreak of a third global war. UNCLOS is an integral part of this international order since it forms the basis for a common understanding of how nations use oceans and their resources.

The PRC and Philippines are both parties to UNCLOS. The US has not ratified UNCLOS, but has issued Presidential directives for the executive department to comply with the vast majority of UNCLOS (in particular the provisions pertaining to the issues discussed in this article) since President Reagan’s Oceans Policy of 1983.

The hard truth that American strategists need to finally come to grips with is that the South China Sea is increasingly “China’s Caribbean.” As is well known, the US brooks no external great power intervention in the Caribbean, as proscribed in the Monroe Doctrine.

Washington has always done what it needs to do in this sensitive area for US national security, even if that meant regular military interventions to the point of carving up the country of Colombia in order to build the strategically vital Panama Canal.

In that respect, Beijing has been considerably less aggressive than Uncle Sam was in his rambunctious adolescence.

First, the author seems to be suggesting some type of realist argument by bringing up the Caribbean. From a realist perspective, yes, the fact of US preeminence in the Caribbean existing while the CCP struggles in the South China Sea is “winning.” Just take the win, there is no reason to cede rights, territories, or mutual defense treaty allies’ security buffers because of the author's notion of what China should have.

It would not be in the US national interest to help Beijing make the South China Sea “China’s Caribbean.” It is laughable to think that Washington, let alone US allies and partners that actually live in that neighborhood would accept such an outcome.

Second, is US preeminence in the Caribbean based on a realist policy stemming from the Monroe Doctrine (originally intended to kick Russia out of Alaska, but that is another story) or something else?

The post-WWII basis for collective security in the Western Hemisphere (Canada aside for this discussion) is the Rio Treaty of 1947. In the immediate post-WWII era, numerous Latin American countries worked together diplomatically to get a separate agreement with the US on the postwar collective security arrangement in the new world.

Numerous Caribbean countries are signatories to the Rio Treaty, as late as the Bahamas signing in 1982. Countries have acceded and left the Treaty during its lifetime.

Therefore, the foundation of American military power in the Western Hemisphere is a collective consensual agreement, not the Monroe Doctrine. We cannot hold a modern PRC to US standards from more than 200 years ago. If there is to be some equality between two great powers, and some hope for peace, they must play by roughly the same rules.

To compare the Panama Canal Zone to 2TS is also a strange analogy. To play moral tit-for-tat, over 120 years ago China practiced one of the largest systems of slavery in human history while the US didn’t. But these things are non sequiturs.

The issue at stake is survival of the modern rules-based international order, a system born from the ashes of two world wars with the specific purpose of preventing a third. To try to discredit the modern system by pulling up relics from a past before the system existed is a well-worn circus trick often employed by China and Russia.

It seems the author suggests that satiating Beijing’s appetite for territory is the only dimension important to the maintenance of the modern international system. This could not be further from the truth, since the US has a consensual network of allies which it maintains and which Beijing must respect.

Finally, If China is so peaceful “[that it has not]... resorted to the large-scale use of force in more than four decades,” then the costs of deterrence should be low. Yet the author also seems to suggest that China could escalate to nuclear war over 2TS in some type of spiral. So is China a bellicose dragon ready to nuke the US over a low tide elevation? This seems hard to believe. Or is China a cuddly Panda that never goes to conventional war? This tension in the author’s mind is never addressed.

Conclusion

The author does not articulate a specific strategy or specific approach besides suggesting that Filipino-American cooperation is problematic because it could make Beijing angry. There is also the suggestion that American actions are risky, even though Americans aren’t even involved in the numerous disputes over 2TS besides public reaffirmations of the mutual defense treaty.

What the author is indirectly calling for is some type of engagement, restraint, or detente strategy. These three approaches have failed miserably with the PRC and US adversaries writ large. China hands calling for these types of approaches need to marshal better arguments with far more convincing evidence since these policies failed so totally in the past.

Engagement was certainly the policy pursued for the vast majority of years between 1979 (normalization of relations) and 2017 (US names China a strategic competitor). The US accepted a greatly diminished Taiwan in exchange for a closer relationship with the PRC.

US criticism of the bloody resolution to the Tiananmen protests was muted in 1989. The US still worked towards PRC entrance into the World Trade Organization around 2000, regardless of the communist regime still firmly in power. The trade relationship continues to grow, even to the current year.

What did the US get from decades of engagement with the PRC? Concentration camps in Xinjiang and the largest navy in the world eroding the Philippines’ sovereignty.

Amazingly, during this time period, the US also practiced restraint. This is not something many observers discuss. US military posture in Asia and globally has significantly reduced from Cold War highs. The largest American overseas base complex in the world was located in the Philippines (primarily Clark and Subic). Congress shuttered these bases due to cost wrangling between the Filipino and American senates.

Today, US military forces are significantly smaller with significantly older equipment compared to the Cold War era.

From a 2021 RAND study of restraint strategies, a year before the Russian invasion of Ukraine: “advocates of restraint seek a more cooperative approach with current U.S. adversaries, such as Russia and Iran.”

Could one imagine if the restrainers were running Russia policy? It can be assumed that the critical training Ukraine received from US forces from 2015-2022 would have been canceled, leaving Ukraine the least capable when it is the most vulnerable. The numerous working relationships and touch points that helped Kyiv survive the first dark month of the war may not have been in place.

The US has already tried a strategy of restraint in Asia for decades and failed. This approach has not led to comity between Washington and Beijing; in fact, the CCP only identified an American vulnerability leading to a window of strategic opportunity. At this point, restraint would sellout American allies and partners when they require help the most.

Finally, the strategies of engagement and restraint were always related to the atmosphere of detente, or a lessening of tensions. For the past few decades, Washington has bent over backwards to downplay or reduce tensions surrounding Taiwan, the Sino-Indian border, Japan’s WWII legacy, or the two Koreas. It has bought the American people very little.

The 35+ year policy of engagement, restraint, and detente have been catastrophic. If Beijing were to gain even a small upper hand in Asia during some conflagration in the first island chain, historians would pin the blame primarily on Washington’s policies between 1979 and 2017.

To prevent war and the rise of a regional totalitarian empire, the US needs to reject stale approaches which bear no fruit. Washington must stand firmly with allies and partners shoulder to shoulder while fine tuning coercive approaches to Beijing - clearly communicating the capability to deny Beijing’s military objectives throughout Asia.