PLA Amphibious Ops Series: EP1 - Battle of Kinmen

金门 - Jin1men2 - Kinmen

Kinmen | Dengbu | Hainan | Wanshan | Nanpeng | Dongshan | Yijiangshan | Dachen

This Vermilion series will delve into the decades long history of amphibious operations surrounding Taiwan’s outlying islands and the lessons learned from forgotten battles between the mainland communist People’s Republic of China (PRC) People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Taiwan-based Republic of China (ROC) Armed Forces (ROCAF). These amphibious battles are key to understanding and planning for the modern amphibious invasion of Taiwan, seen by most observers as the powder keg of Asia.

Timeline

October 25, 1949 – October 27, 1949 — Battle of Kinmen

November 3, 1949 – November 5, 1949 — Battle of Dengbu Island

March 5, 1950 – May 1, 1950 — Landing Operation on Hainan Island

May 25, 1950 – August 7, 1950 — Wanshan Archipelago Campaign

September 20, 1952 – October 20, 1952 — Battle of Nanpēng Archipelago

July 16, 1953 – July 18, 1953 — Dongshan Island Campaign

January 18, 1955 – January 20, 1955 — Battle of Yijiangshan Islands

January 19, 1955 – February 26, 1955 — Battle of Dachen Archipelago

The Battle of Kinmen - October 1949

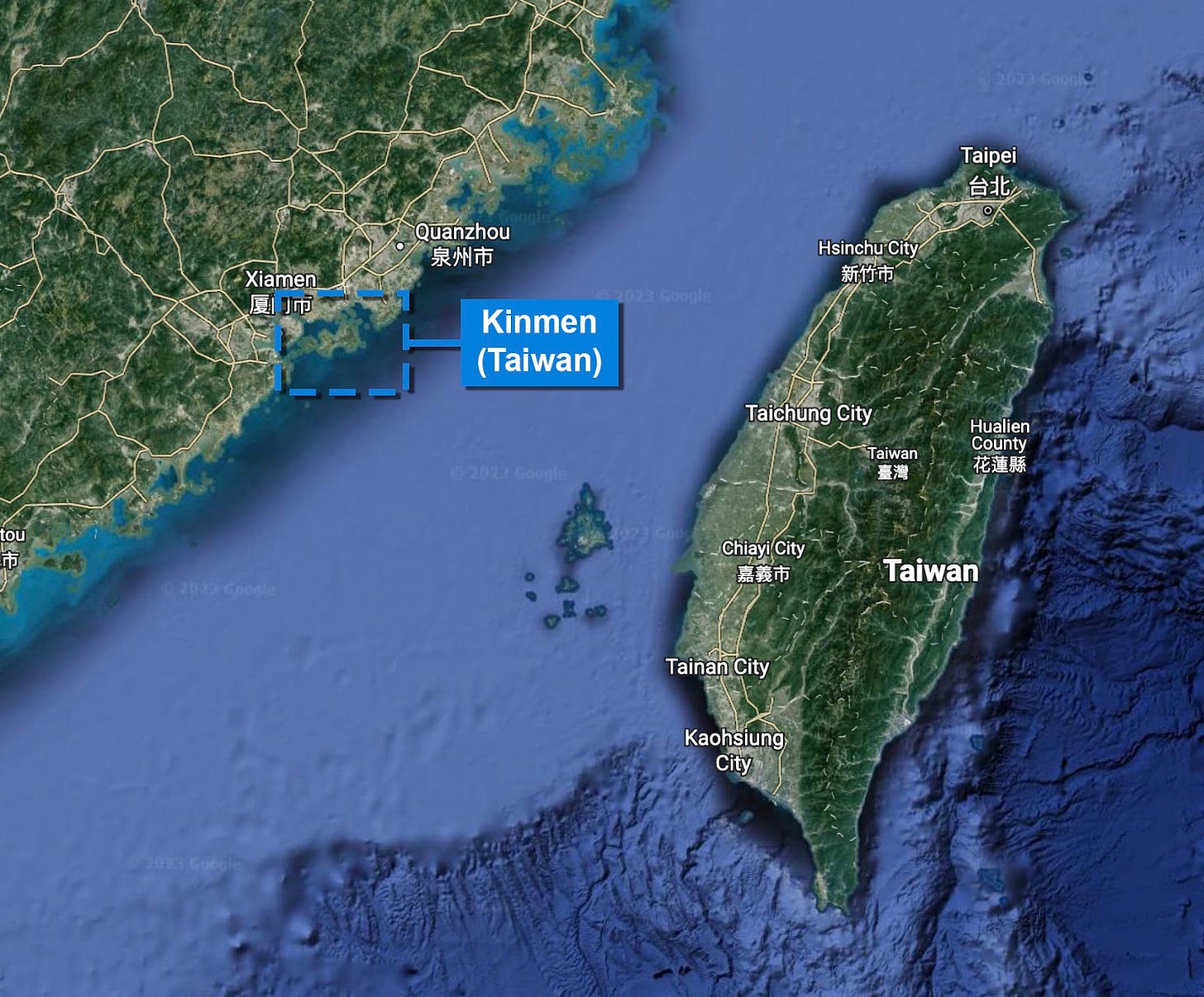

A major portion of the ROC’s outlying islands are administratively grouped together as Taiwan’s Fujian Province. This province is composed of two counties, Kinmen County (金门县 also known as Quemoy) and Lienchiang County (连江县 also known as Mazu). Both are collections of small islands directly off the coast of communist mainland China, making these counties inherently difficult to defend from Taiwan’s perspective.

Kinmen County is a collection of six islands located just 10 kilometers east of Xiamen, a major city in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The largest of the Kinmen Islands, also named Kinmen, is roughly 130 square kilometers (roughly twice the size of Manhattan Island) and is home to Jincheng Township as well as Shuitou Harbor, the main port for the island group. Lesser Kinmen Island (Lieyu Township, 列屿) is approximately 15 square kilometers. Also administered by Lieyu Township are the chain of small islands to the west of Lesser Kinmen (Menghu, Dadan, Erdan, and Sandan) which have a combined size of approximately 1 square kilometer.

Often, small islands can have outsize importance. The battle for Snake Island in the early phase of the Ukraine War is testament to the enduring significance of littoral features. For reference, Snake Island is about 0.2 square kilometers in size.

Terrain & Weather

Kinmen Island is relatively flat with small undulating hills in the east culminating in two peaks, Nantai Wu Shan (南太武山) and Wuhu Shan (五虎山), respectively 253m and 127m in elevation. From these vantage points, Kinmen and Xiamen are mutually visible. The hills and mountains on the eastern side of the island are almost entirely composed of granite gneiss whereas the western side of Kinmen and the other islands that comprise the Kinmen island group are a combination of granite gneiss, laterite, and basalt. This means that with significant effort, defenders can construct near impenetrable cavern systems through the islands. Additionally, Kinmen is famous for its unpredictable intense winds that often blow across the island. The wind conditions are so extreme that local religious worshippers view the Wind Lion Gods as the ultimate guardians of Kinmen.

Road to War

In the autumn of 1949, Republic of China Armed Forces (ROCAF) suffered a series of military defeats on mainland China. After the fall of Beijing, communist forces established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949. In response, ROCAF withdrew from the mainland and retreated mostly to either Taiwan or islands off the coast of Southern China (including Hainan, the Matsu Islands, the Dongji Islands, and many others that Vermilion will cover in future posts).

Despite the vast majority of ROCAF pulling out of mainland China, the leader of the ROC, Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石) tried to maintain a hold over critical ports in Southern China, Xiamen included. Ultimately these efforts were unsuccessful as the PLA launched an invasion on October 15, 1949. During the Battle of Xiamen, the PLA annihilated approximately 27,000 ROCAF troops with the remainder, roughly 20,000 troops, fleeing to Kinmen. To the communist leadership, the end of the Zhangxia Campaign (漳厦战役 - CN) to assert control over the entirety of Fujian province was in sight. The only obstacle left was Kinmen Island, blocking the strategic harbor of Xiamen.

Mao Zedong (毛泽东), the leader of the new PRC, was eager to capture Taiwan before United States involvement precluded the possibility of total communist victory over the ROC. Mao ordered Su Yu, the commander of the PLA Third Field Army, to develop a plan to capture Taiwan no later than the winter of 1949. This extreme level of urgency and unrealistic timeline shot through the ranks of the PLA like a lightning bolt. The first logical step of a Taiwan campaign would be the complete conquest of Fujian in order to open an uncontested sea route from Xiamen to Taiwan. The only way to accomplish this was to seize Kinmen from the ROC in order to support follow-on operations. General Xiao Feng, the commander of the PLA 10th Army Group’s 28th Corps (roughly 35,000 troops), was selected to execute the Kinmen operation.

PLA Assault Preparation

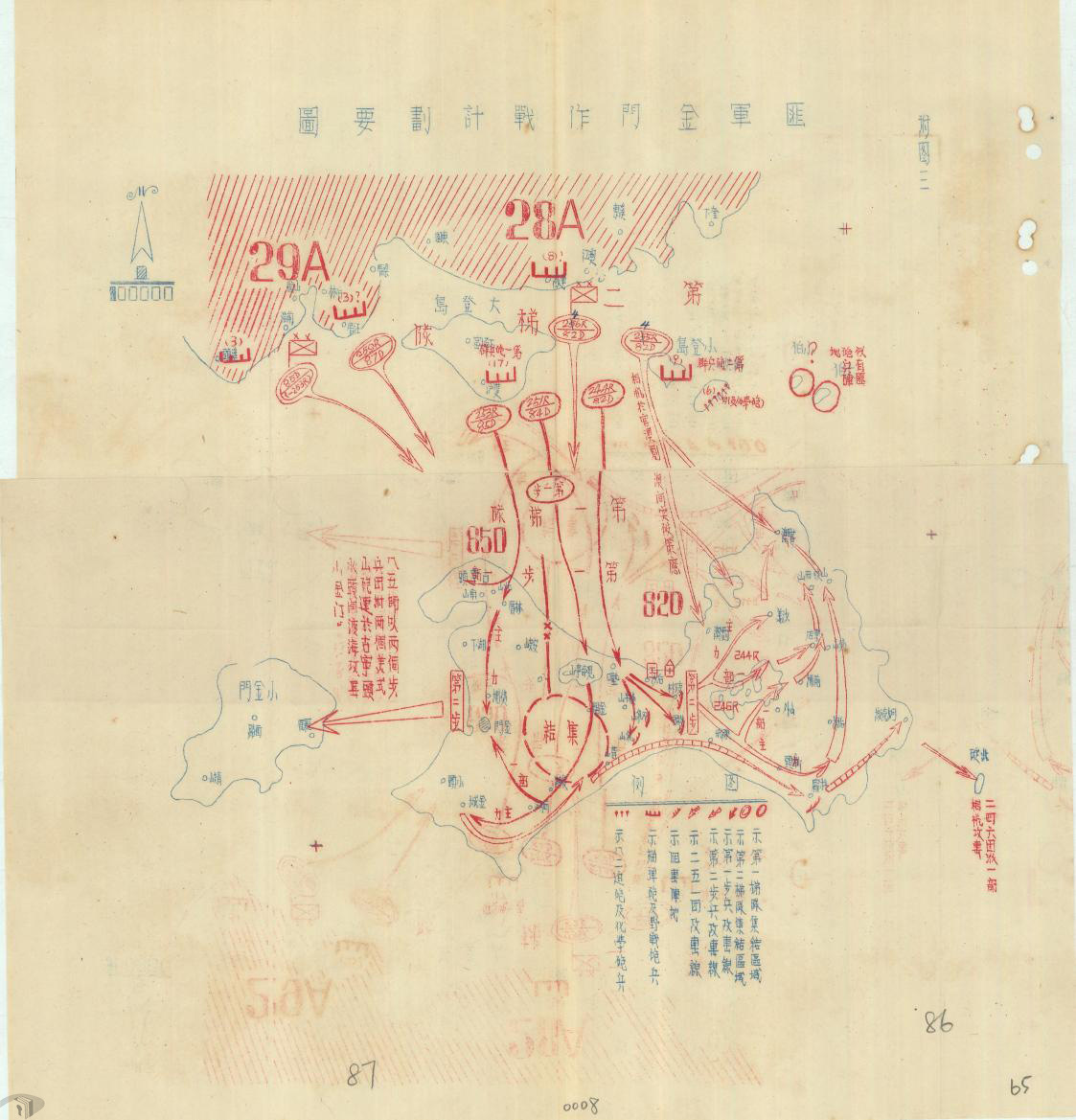

Xiao Feng’s plan was to land the entire PLA 28th Corps on Kinmen in a single wave by commandeering roughly 800 fishing boats and transport ships. After landing, the troops would assault over the beach and attempt to break out by seizing small villages along the central coast. After seizing this line of small villages, follow-on forces would then push across the island and engage the 20,000 ROCAF troops who previously withdrew from Xiamen. Xiao Feng fatefully assumed that these defenders, while possibly supported by tanks, were demoralized, low on supplies, and only equipped with small arms

Critical to the success of the first wave amphibious assault was the PLA capture of fishing boats during the Battle of Xiamen. It was only by having enough amphibious capacity that the PLA could land enough forces on Kinmen to overwhelm the defenders with numerical superiority. Yet Xiao Feng did not anticipate that during the Battle of Xiamen, local fishermen would resist by sailing away from the area in order to prevent their vessels from being commandeered by communist forces. Between fishermen resisting the PRC and the ROC air force bombing transport ships, the 28th Corps had only 300 fishing boats on hand to participate in the operation, less than half of what was required for the plan.

In light of this development, Xiao Feng decided that he would split his 28th Corps into two waves. The first wave would secure the beachhead and the villages of Qionglin (琼林) and Longkou (咙口) at the center of Kinmen. Immediately after dropping the troops ashore, the boats would turn back to pick up more PLA troops. Then, the second wave would use the captured villages as assembly areas to continue the attack and capture the whole island. Impressively, in only eight days after securing Xiamen, the 28th Corps was prepared to assault Kinmen Island.

Little did PLA planners realize that the true ROCAF troop count on Kinmen numbered approximately 40,000 soldiers reinforced by a light tank regiment (1st Battalion, 3rd Tank Regiment) consisting of 21 US produced M5A1 Stuart light tanks. These tankers were seasoned veterans of the WWII Burma campaign. Hard combat experience fighting against the Japanese was to serve as an excellent guide to 1/3 tanks leadership. Additionally, the Kinmen garrison spent significant time constructing over 200 bunkers and lined the shores with nearly 7,500 landmines. ROC troops were prepared for the coming storm.

The Amphibious Assault

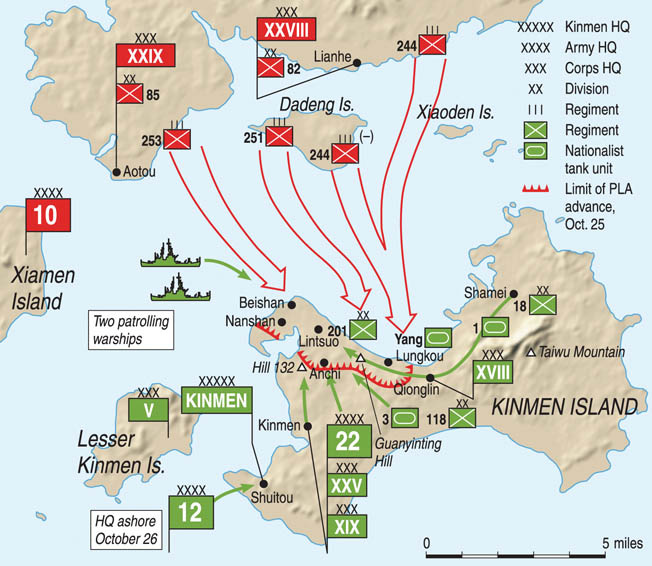

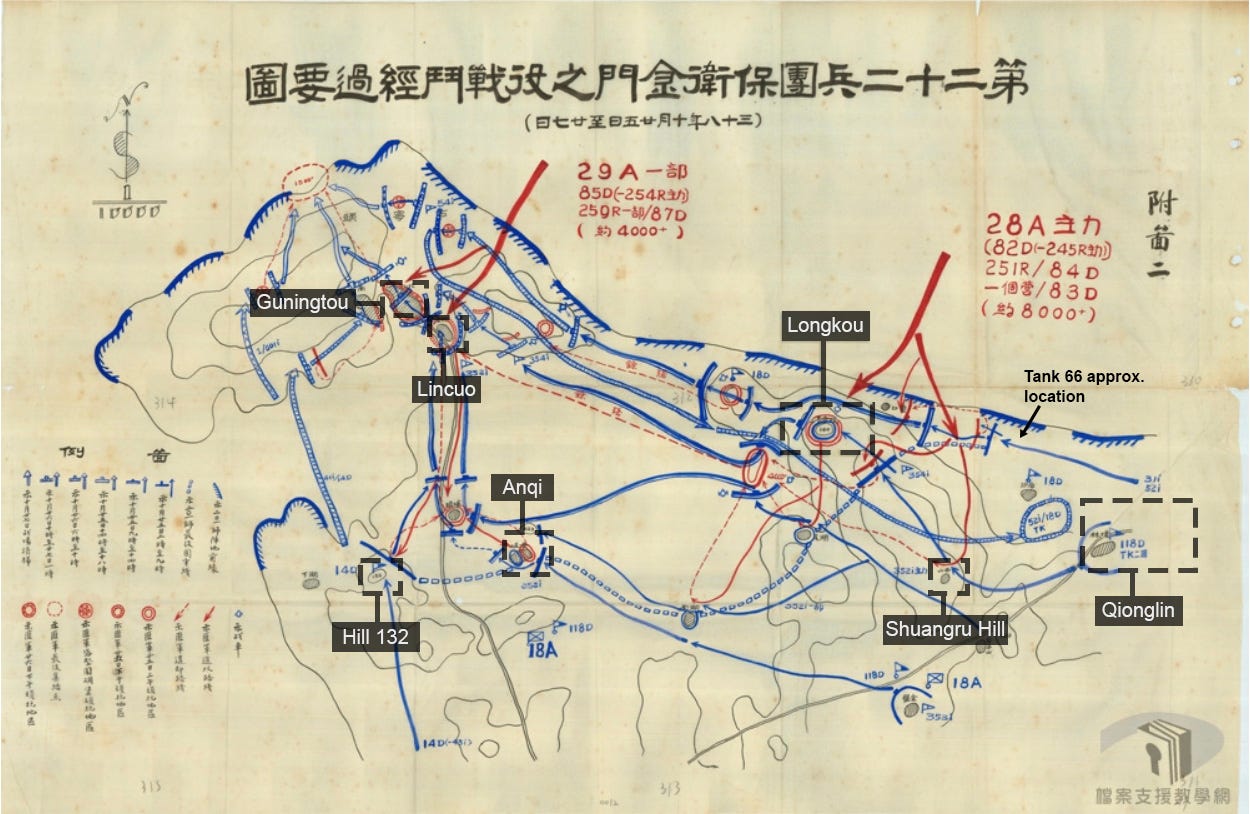

On October 24th, the first wave of PLA troops ( ~9,086 soldiers) set off in their makeshift troop transports towards Kinmen. The 244th Regiment was given the objectives to seize Qionglin and Longkou, while the 251st and 253rd attacked further west between the Huwei River and Guningtou (古宁头), a village at the western tip of the island. In traditional PLA fashion, this was a night assault. Shortly after embarking, the first wave started to encounter coordination problems. Illumination on October 24th, 1949 was approximately 14%, meaning that the fishermen the PLA impressed into service had difficulty navigating. This combined with strong winds blowing southwest pushed the assault force off course, an issue compounded by the fact that none of the troop transports were motored. As a result, the bulk of the landing shifted to an area between Longkou and Guningtou.

At approximately 0200 on October 25th, PLA troop transports started hitting the beaches. Unfortunately for the attackers, a ROCAF patrol tripped their own landmine at almost the exact same time, causing defenders to light up the beaches with flares. ROCAF troops immediately began firing on PLA soldiers with twelve 57mm anti-tank guns, mortars, and four 75mm howitzers (these were located on the east side of the island). Since the PLA operation was quickly planned and the nature of the attack relied on stealth and small ships, planners eschewed artillery or other heavy support equipment in the amphibious load plan. PLA forces ashore were left to fight with handheld assets.

Conversely, ROC troops were almost immediately overwhelmed in the west and elements of the PLA 251st and 253rd Regiments pushed off of the beach to take control of Guningtou, Nanshan (南山), and Jinning (also known as Hill 132, approximately 5 km north of Jincheng, the county seat). However, there were a series of following events that tipped the battle in favor of the ROC.

During the previous day on October 24th, several M5A1 light tanks were conducting anti-invasion exercises along the beach directly north of Qionglin. During these exercises, one of these tanks (Tank 66) got stuck in the sand and was unable to move all night until it was pulled out at 0300 on the 25th. This meant that it was coincidentally directly in the path of the PLA 244th Regiment during their landing. When the PLA landed at Qionglin, the tankers heard their movement and then saw the enemy boats when the signal flares were fired. The commander of Tank 66 began to open fire on the enemy, ripping through PLA ranks with the 37mm main gun and .30 caliber machine guns.

By sheer luck, a shell from 66’s main gun hit the mast of one of the transports and ignited the sail. The fast Kinmen winds spread the fire across multiple boats, providing illumination for the defenders. PLA troops assaulting up the beach were perfectly backlit by their own burning boats while attempting to identify ROC positions covered in darkness. Shortly after Tank 66 opened fire, it was joined by two additional tanks from its platoon. The tank fire completely halted the 244th Regiment’s advance at Qionglin and forced the regiment to begin moving north towards Longkou.

ROC navy warships also played a critical part in the battle, but it was only a twist of fate that led the vessels to be present on that day. Two days before the assault, the officers and sailors of the Zhongrong, a tank landing ship (LST), purchased brown sugar in Taiwan to sell in Zhejiang. However, at the last minute the ship’s destination was changed by ROC HQ and the Zhongrong received orders to transport elements of the ROC 19th Army to Kinmen in order to bolster defenses.

The Zhongrong arrived at Kinmen on October 24th. The crew, realizing they were unable to continue on to Zhejiang, opted to trade their brown sugar to Kinmen locals in exchange for peanut oil. Unfortunately for the ROC sailors, Kinmen had an insufficient amount of peanut oil on hand and the Zhongrong would have to stay an additional day to load the remaining balance. This ironically put them in prime position to assist the defenders in the early hours of October 25th.

At approximately 0230 the Zhongrong and the Nan’an (a 150 ton light gunship) swung around the northwest coast of Kinmen to join battle. The vessels employed their Bofors 40mm anti-aircraft guns, 20mm cannons, and machine guns to annihilate the remnants of the 251st and 253rd Regiments strung along the beach. Crucially, PLA planners did not heed the pleas of the fisherman and landed during high tide, stranding many of the troop transports along the Kinmen mud flats. The Zhongrong and Nan’an, now joined by the Hui’an, another light gunship, proceeded to destroy stranded vessels along the coast one by one. The forsaken first wave was forced to bide its time.

By 0300 communication between the PLA forces on Kinmen had broken down and the three regiments were now fighting independently. At this time, Liu Tianxiang, commander of the 253rd Regiment, radioed Xiao Feng telling him that they had successfully landed and taken Guningtou and Nanshan. He did not know that ROC vessels were destroying the first wave troop transports and that his force was rapidly being isolated.

Retreat to Guningtou

At 0600, all PLA troops were off the beach and had pushed inland to varying extents. The 244th Regiment had captured Shuangru Hill (双乳山) in the center of Kinmen and was barely hanging on. The 251st Regiment had secured Guanyin Hill (观音山) and the road to Anqi Village (安岐) and was beginning to dig in. The 253rd Regiment had moved south past the village of Lincuo (林厝) to Hill 132 and was also preparing a hasty defensive line.

While the attackers were digging in, the remaining tank units were pushing westward from their positions in the south and east, and the bulk of ROC infantry were moving north to Hill 132 from Jincheng.

As the ground battle continued, the ROC utilized an additional advantage, complete domination of the skies over the Kinmen and the surrounding operating environment. A local infantry commander was a prior air force officer who functioned as a forward observer. He used this experience to successfully direct air strikes against PLA troops throughout Kinmen. The Air Force also destroyed additional transport ships and raided PLA outposts along the shores of Xiamen, further diminishing any hopes of a second wave from the PLA 28th Corps.

By the evening of the 25th, the 244th Regiment was destroyed with the commander killed in action. All remaining troops fled west to Guningtou and Lincuo to join the remnants of the 251st and 253rd Regiments who had also been forced out of their positions. Xiao Feng made attempts to reinforce the regiments during the day, but was unable to get troops across the water because of ROC naval forces and air raids.

Battle of Guningtou

During the night, PLA reinforcements were able to embark from Xiamen and land on Kinmen. After fighting a running battle to break through ROC lines, this PLA column arrived at Guningtou on 0300 of the 26th numbering about 1,000 combat effectives. The reinforcements were welcomed by the remnants of the first echelon, but their functionality was limited due to their lack of heavy weapons and ammunition. The PLA’s only choice was to occupy the buildings of Guningtou and Lincuo and prepare for the ROC onslaught.

At 0630 the ROCAF launched their assault on the PLA positions. After engaging the PLA in close urban combat, ROC air force medium bombers (B-25s and B-26s) and naval gunfire bombarded the town, helping to dislodge the enemy from Lincuo. Once the enemy abandoned these positions, the Guningtou area was effectively turned into one large kill box.

The aerial bombardment of the town continued throughout the day and fighting between the PLA and the ROC continued with heavy urban combat and hand to hand fighting as both sides ran low on ammunition. According to the legend of the “Bear of Kinmen” (金门之熊), the M5A1 Stuarts ran out of ammunition and proceeded to drive through the town, running over PLA soldiers and creating gaps in their lines for the ROC to advance through. The PLA forces lacked anti-tank equipment and failed to stop the ROC tanks with small arms and grenades. By 2200 on the 27th, the remaining PLA troops evacuated the town and made their last stand on the beaches to the north of Guningtou. Here they exhausted the remainder of their ammunition and were surrounded by ROC forces. After taking approximately 400 casualties on the beach alone, the remaining soldiers surrendered and ROC troops began to mop up the rest of the island.

Of the 9,086 PLA soldiers who fought on Kinmen, 5,175 were captured and the remainder were killed in action. None returned from the battle. The ROC, while victorious, suffered 1,267 killed in action with an additional 1,982 wounded.

Aftermath

The defeat at Kinmen was the first major PLA defeat during the Chinese Civil War and caused Mao and Su Yu to modify and ultimately shelve their plans for the Taiwan assault.

Lessons:

The assaulting force must command the skies and the sea around landing zones and objectives.

In 1949, the PLA “navy” largely consisted of fishing boats and junks. This “People’s Flotilla” (their term for requisitioning civilian vessels) would have to suffice for a few years before the PRC could produce or procure warships. As a result, the PRC had little ability to control the seas around the landing zone. While the PLA did have a fledgling air force, the majority of the PLA’s planes were in Beijing for military parades that took place earlier in October.

The combination of these two factors meant that the invasion force was completely exposed to ROC combined arms with little ability to react.

Amphibious operations require an extensive study of local hydrography, weather patterns, and terrain.

It is obvious, but planning and executing an amphibious operation is not similar to standard ground warfare of the type conducted by the PLA during the Chinese Civil War. It is quite literally planning a ground action upon the changing, chaotic sea. The PLA did not account for shifting tides, extended mud flats, or high winds cutting across the landing areas. These natural features blunted the assault’s initiative and caused confusion and casualties during the landing phase. To compound the PLA planners’ mistakes, even normal ground planning factors were not considered, such as night illumination, obstacle reduction, and fire support.

Land the heaviest weapons as early as practical.

The key component of amphibious assault is the ability to rapidly build up combat power at the landing zone in order to achieve breakout. To accomplish this, the landing force must be tailored to meet potential challenges immediately at the landing zone and have the equipment necessary to overcome superior enemy positions and firepower. The landing force, regardless of whether the operation will be an amphibious landing or amphibious assault, must be packed and then unloaded at the beach as if the operation were an assault. At Kinmen, the PLA knew that tanks were a possibly yet opted to send their anti-tank weapons in the second wave. As a result, the assaulting force had no ability to counter the M5A1 Stuarts of 1/3 tanks.

Have a marshaling plan.

Amphibious operations often utilize hundreds of ships. Each vessel needs to have clear guidance on where they are going and what they need to do once they get there.

In the case of Kinmen, there was no plan once the troop transports reached a designated rally point and units were mixed together, with many troops landing on the wrong beaches. Additionally, there was no plan to recover the transports once they unloaded. PLA staff were relying on civilian coxswains to bring the boats back for the second echelon.

Plan for the catastrophic loss of the first wave.

Amphibious operations are inherently volatile. It is entirely possible to lose most of the first wave but still end up victorious. During Operation Overlord, the amphibious invasion of Normandy by the Allies during WWII, Omaha beach landing companies of the 29th Infantry Division suffered 90%+ casualties. The men and material landing first must be completely written off during planning. The PLA violated this dictum and counted on first wave boats returning to ferry second wave troops.

Have a unified command.

An assault force must have a unified command structure so adjacent units are able to deconflict and/or work together to seize objectives. At Kinmen, the three PLA regiments had three separate commands, meaning that there was no coordination and each unit was fighting a battle independent of the other assault forces.

The objective must be isolated.

Recon, isolate, seize a foothold, secure the objective. These are inherent components of an offensive scheme of maneuver and hold true in an amphibious assault as well. The PLA did not isolate their objective and the ROC had freedom of movement on, around, and to the island. This allowed defenders to flow freely throughout the island and maneuver around the assaulting force. This led to the PLA’s own isolation and ultimate crushing defeat.

Communications must be established between beachhead forces and the rearward headquarters until C2 can be established ashore.

Once the assault force is ashore, the command element must establish immediate communications with headquarters and update them on the status of the assault. This will allow them to coordinate/reposition fires and supporting elements to better assist the assault. The PLA had no coordinated communications and they were not able to provide accurate battlefield estimates to headquarters.

The assault force must have overwhelming quantitative superiority and outnumber the defender 3:1 at the absolute minimum.

There is an axiom of attack that gives an advantage to defenders by a margin of 3:1. This means that in order to overwhelm defenders and ensure victory, attackers must bring at least 3x the number of combat troops. At Kinmen, the first wave put the ROCAF quantitative advantage at 4:1 over the PLA. The total advantage of the ROCAF over the PLA was by a margin of 4:3. By numbers alone the PLA had little chance of success.

See below for a chart on US numerical advantages during various amphibious assaults during WWII. Table created by Navy Matters.

Complex military operational objectives cannot be subordinated to political strategic timelines.

Operational timelines cannot be tied to arbitrary political timelines. This causes mistakes that will ultimately render a military unable to achieve its objectives.

Mao’s sense of urgency, partially tied to a notion that the US would get involved in the war, caused PLA commanders to speed up their operational timelines. This meant that they did not have adequate resources to achieve their operational goals and this set back the entire communist strategic timeline.

Timeline

October 25, 1949 – October 27, 1949 — Battle of Kinmen

November 3, 1949 – November 5, 1949 — Battle of Dengbu Island

March 5, 1950 – May 1, 1950 — Landing Operation on Hainan Island

May 25, 1950 – August 7, 1950 — Wanshan Archipelago Campaign

September 20, 1952 – October 20, 1952 — Battle of Nanpēng Archipelago

July 16, 1953 – July 18, 1953 — Dongshan Island Campaign

January 18, 1955 – January 20, 1955 — Battle of Yijiangshan Islands

January 19, 1955 – February 26, 1955 — Battle of Dachen Archipelago

Notes

The records of which PLA units landed on which beaches are highly dubious because of translation issues and conflicting information between China and Taiwan. We have tried to clarify this and will continue to update this article when new information arises.

Primary References:

古宁头战役 《Battle of Guningtou》Taiwan Navy Research Paper

第三野战军战史 《History of the 3rd Field Army》Nanjing Area Army Library

Chinese Warfighting: The PLA Experience since 1949