Beijing and New Delhi Wrangle Over the Indian Ocean

A clash of regional and global interests

Over the past few weeks, competition between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India for influence in the Indian Ocean is once again heating up. On 31 Dec, Sri Lanka announced a one year moratorium on Chinese research vessels operating within Colombo’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

“The ban on Chinese ships in Sri Lanka’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is seen as a “victory” for India in the Indian Ocean but also highlights the limits of small states “in maneuvering between major powers”, analysts said.

The one-year moratorium also points to China’s inability to leverage its investment in developing countries to serve its growing military ambition, experts added.

On December 31, Sri Lanka said it had informed India that it would not allow any Chinese research vessels to dock at its ports or operate within its EEZ for a year, the Hindustan Times reported.”

The PRC struck back on 14 January, when the Maldives called for India to remove all troops from the country by 15 March.

The Maldives has called for India to withdraw troops from its territory by March 15, an official said on Sunday, in a step that will further strain ties between the South Asian neighbours.

President Mohamed Muizzu won the election last year on a pledge to end the Maldives' "India first" policy, in a region where New Delhi and Beijing compete for influence.

A contingent of around 80 Indian soldiers are stationed on the Indian Ocean archipelago to provide support for military equipment given to the Maldives by New Delhi and assist in humanitarian activities in the region.

Why are these long ignored areas now getting renewed attention?

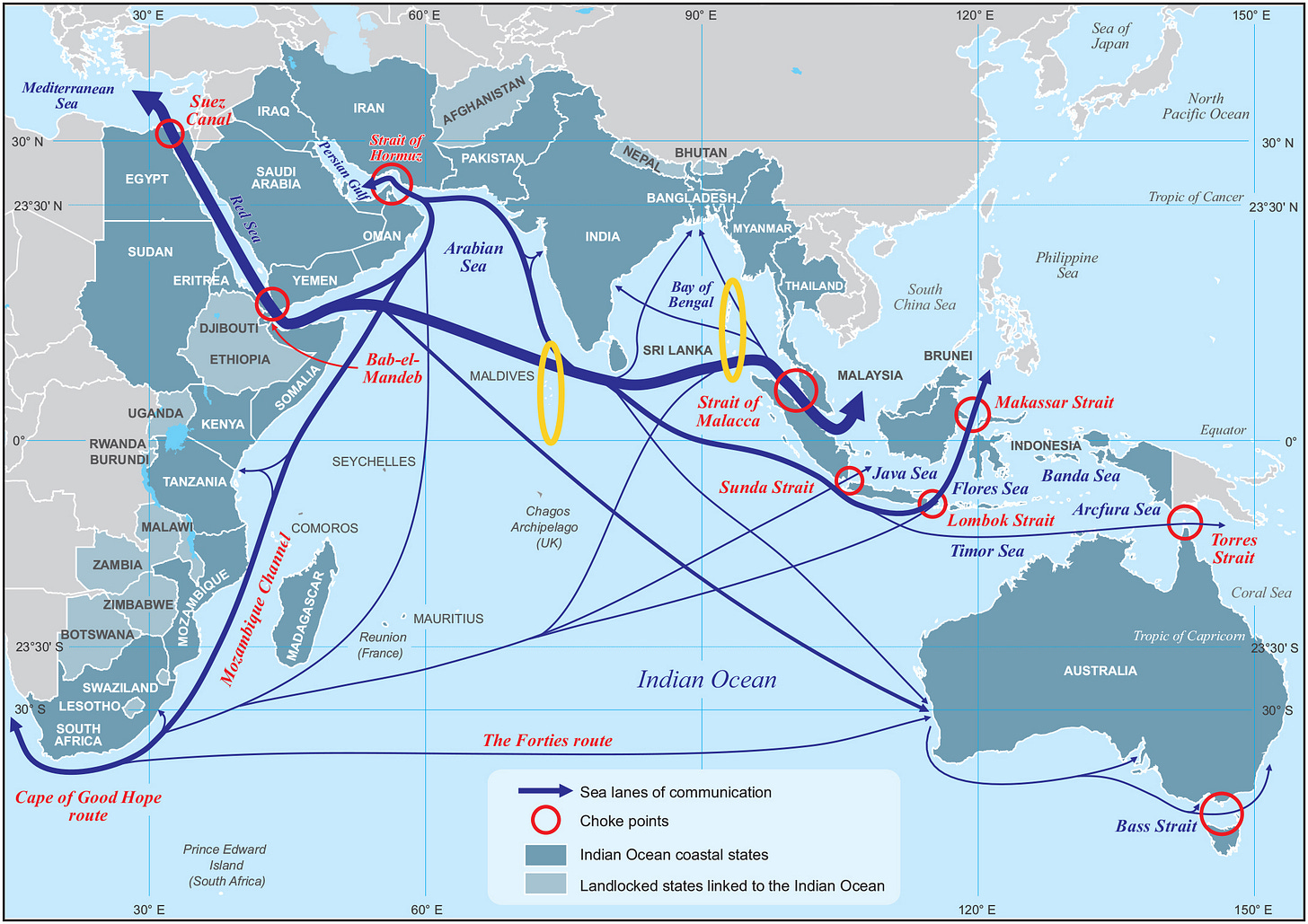

The Maldives, Sri Lanka, and the Andman & Nicobar Islands have often been neglected in favor of the periphery of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). A series of critical choke points along the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Sea, and the straits of Indonesia are where the majority of security threats emerge (as with the ongoing situation in the Red Sea). While these areas will always be of strategic importance, there is a shift in focus from both India and the PRC to islands and island chains within the greater IOR. As with almost every other situation, it comes down to geography.

Sri Lanka makes the news more often than the Maldives and Andaman & Nicobar because it is a major trading hub along the Indian Ocean. Just like some other countries (looking at you, Taiwan) it often finds itself at the crossroads of other peoples’ journeys. A cursory google search will lead to results such as Belt and Road Initiative projects gone awry, US funding for a new shipping terminal at the Port of Colombo, and now the Sri Lankan Navy’s participation in Operational Prosperity Guardian.

The same search for the Maldives and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands yields results like the one below.

Unlike Sri Lanka, however, the Maldives and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands are linear island chains within the IOR that cut across the main trade routes in the region. This is highlighted above in Image 1. Whoever can control and project power from these natural blocking features will have an outsized impact on sea lines of communication (SLOCs) in the IOR. This is a reality that both India and China are acutely aware of.

Since 2019 India has embarked on a series of massive upgrades to civilian infrastructure and military bases in Andaman and Nicobar. Runways at air bases were extended, fiber optic cables were laid to improve communication resilience, and a $5 billion shipping terminal on Great Nicobar Island is in the works. In addition to this, the Andaman Nicobar Command (ANC) is the nation’s only tri-service command and it regularly conducts combined patrols with partner navies. By dominating the western entrance to the Malacca Strait, India can monitor and potentially prevent hostile movement into the IOR via the Malacca Strait.

From China’s perspective, India’s presence in this specific location is a serious national security concern (“a threat to China’s sovereignty”). The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) highlighted this in 2004 when Hu Jintao, then President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and general secretary of the CCP, coined the term the “Malacca Dilemma” (马六甲困局). In short this was Beijing’s public recognition of its vulnerability to a hostile nation disrupting trade in the Malacca Strait, thus tying the entire IOR to China’s core interests and giving Beijing an excuse to assert dominance over the region. The question for Beijing then became how to mitigate this concern.

Immediate reactions included a plan for the Kra Canal, a canal project that would cut through the Kra Isthmus and allow maritime traffic to bypass the Malacca Strait. Despite ongoing conversations, no progress has been made on this over the past nearly two decades.

Aside from this, China recognized the best option would be to win over governments in or around the IOR (Maldives, Burma, Sri Lanka, Seychelles, Djibouti, etc.). In direct opposition to the Indian military presence in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, China has continued to develop what are almost certainly military facilities on Great Coco Island (Burma/Myanmar) just 55km north of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. In 2016, China also unveiled its first official overseas military base in Djibouti.

These military developments are compounded by China’s encroachments on India’s northern border, regular “research expeditions” (terrain mapping for submarines) in the IOR, China’s military and economic support for Pakistan, and China’s political maneuvering within India’s natural sphere of influence. All of these actions threaten India’s control over the IOR and shift the regional balance of power towards China. From the Chinese perspective, India’s regional claim over the IOR is subordinate to China’s own regional claim of sovereignty over Taiwan and the South China Sea, an ambition that requires global protection of SLOCs as part of the “two ocean strategy” (双海战略). Essentially the idea that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) must have the ability to “fight and win battles” in the “near seas” (近海) and be able to protect SLOCs in the “far seas” (远海).

Who Has the Upper Hand?

As of early 2024, India still has military dominance in the IOR and is assisted by potentially friendly forces stationed in the Middle East and Diego Garcia.

In regards to diplomacy, India is sitting in second place. China is doing a better job working with local elites and influencing regional actors who have the ability to collectively sway the balance of power in the IOR. An example of this is the Maldives. If China can establish surveillance facilities in the Maldives and expand signals intelligence capabilities in the region, the PLA will be able to more effectively monitor military traffic, something that could allow the PLA to identify trends and improve targeting capabilities.

India must recognize that their inability to navigate through their own backyard will likely have far reaching implications. New Delhi’s regional issues will only remain regional until the PRC takes decisive strategic action affecting the global balance of power.