#37 - The Marine Littoral Regiment

The Controversy Continues

What is the Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR)?

In terms of design philosophy, the MLR was conceived by the United States Marine Corps (USMC) as a naval formation able to achieve multi-domain (air, sea, land) effects through missiles and sensors. The MLR is built to operate under the constant threat of enemy precision guided munitions. As of late 2022, the MLR was roughly half the size of a traditional Marine Regiment and is designed to accomplish the following missions:

• Conduct Strike

• Coordinate Air and Missile Defense Actions

• Support Maritime Domain Awareness

• Support Surface Warfare

• Support Operations in the Information Environment

• Conduct Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (which supports the 3 missions of Sea Denial, Sea Control, and Fleet Sustainment)

By the Marine Corps’ estimation, the currently in process standup of 3rd MLR and 12th MLR will give the USINDOPACOM combatant commander, Admiral Aquilino, the ability to conduct sea denial operations (through Advanced Expeditionary Base Operations) by the end of 2023.

In terms of total force design, it is important to note that the MLR does not replace the Marine Corps’ traditional amphibious assault capable units, it simply reduces them. The Corps still maintains the forces and traditional concepts to deploy Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs) able to conduct amphibious assaults/joint forcible entry operations.

In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the Corps maintained 24 infantry battalions force wide. By early 2022, 3rd MLR was activated at the cost of two infantry battalions. By the end of the year, Commandant Berger and Marine Corps leadership made the decision to stand down an extra infantry battalion, bringing the Corps to 21 battalions force wide. Marine infantry will likely be held steady at this level for the next 5 years. 12th MLR was converted from the 12th Artillery Regiment, arguably the fire support for the battalions already removed from USMC structure.

Activating the next MLR will be trickier. As slated, 4th Marine Regiment is scheduled to transform into 4th MLR before 2030. This is an infantry regiment, and may necessitate the reduction of two more infantry battalions. However, keep in mind that the MLR is currently around half the size of a traditional Marine regiment (which could change), and a single battalion has already been drawn down from the infantry structure. Marine Corps leadership may be counting on at least a modest budget increase to fund the creation of the 4th MLR.

What Constitutes a Marine Littoral Regiment?

Each MLR is composed of five subordinate battalion elements: a Headquarters Company, a Communications Company, a Littoral Combat Team (LCT), Littoral Anti-Air Battalion (LAAB), and a Combat Logistics Battalion (CLB). The headquarters company is likely a staff similar to any regiment/brigade-sized military unit. The other units are described below:

Littoral Combat Team (LCT) & Communications Company

The Littoral Combat Team is built around an infantry battalion. The task of the infantry is to secure multiple platoon to company-sized base sites from which to operate sensors, fires, forward air logistics points, or a combination of these.

This infantry force will be lighter in manpower than the traditional Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) Ground Combat Element (GCE). LCT Marines will operate from highly dispersed platoon to company sized sites likely without a robust ability to provide mutual support. As the final design of the MLR is in flux, it is not even certain that the mortars typically organic to a Marine Regiment will make the cut. From these design choices, it is clear that the LCT is not meant to go toe-to-toe against an enemy regiment. The LCT must be light and agile, able to destroy enemy reconnaissance units and other small formations, then communicate that contact to the rest of the MLR so it can displace or shift positions.

These communications requirements call for far longer range and better encrypted (since the LCT will operate far forward and well within the enemy electronic collection zone) communications equipment emitting harder to detect signals than is currently equipped. To satisfy this requirement, the MLR will also have a separate communications company in addition to the LCT, LAAB, and CLB. This comms company “will provide command and control capabilities to Marines distributed across wide areas of the Indo-Pacific region.”

Large, high quality optics and drones would be very useful for the LCT to identify targets far out to sea and on adjacent islands. The problem is that these types of equipment are heavy, battery-powered, and can require multiple operators. The already reduced rifleman power of the LCT will have an increased manpower tax for employing these types of systems.

Two Naval Strike Missiles (NSMs) mounted on a Remotely Operated Ground Unit for Expeditionary (ROGUE) Fires vehicle. These two systems combined make the NMESIS.

The LCT replaces its conventional artillery for an unmanned anti-ship battery currently equipped with the Navy Marine Corps Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System (NMESIS). NMESIS allows the LCT to target surface warships (like the Renhai, Luyang, Yushen, Yuzhao classes, etc). The Naval Strike Missiles (NSMs) fired from the NMESIS have a modest 200-250km range. However, the NSM is a cruise missile capable of sophisticated attack routing, able to strike an air defense bubble where it is most vulnerable. Additionally, the NSM has a sea skimming mode, allowing the missile to drop to the height of the waves for its terminal attack in an attempt to avoid radar identification.

In terms of the tactical picture, the LCT can secure portions of an island and destroy enemy surface vessels that get too close, creating a small friendly bubble in a sea of enemy platforms. In operational terms, the LCT is able to create small seams/gaps in the enemy’s surface fleet and situational awareness. Ideally, the US Navy or US Air Force would then be able to maneuver platforms into and through these gaps to take multiple missile shots against the enemy, causing serious damage.

Littoral Anti-Air Battalion

Less has been released on the Littoral Anti-Air Battalion, but there are some high confidence inferences that can be drawn. The Marine Corps has historically fielded Low Altitude Air Defense (LAAD) and Light Anti-Aircraft Missile (LAAM) Battalions primarily equipped with FIM-92F Stinger man portable air defense system (MANPADS), Avenger, and Improved Homing All the Way Killer (I-HAWK). During combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Marine Corps divested itself of the Avenger and I-HAWK systems but retained Stinger MANPADS. This Stinger capability will almost certainly be resident in the LAAB and likely issued to the LCT as well.

The Stinger is a very short range air defense weapon and the MLR will need to pack more anti-air punch. The system likely to fill this role is the USMC Medium Range Interceptor Capability (MRIC) currently in development. The Marine Corps could have simply purchased the US Army PATRIOT air defense system, but the MRIC has very important differences from PATRIOT that make it more suited for the MLR mission.

A test of the Medium Range Interceptor Capability (MRIC)

First, the MRIC is the result of a fusion between US radars (G/ATOR) and Israeli missiles and software (Iron Dome). The advantage of using mostly US radars is that they are more easily able to integrate into the larger US military common operational picture. The advantage of Iron Dome is that the system is physically smaller (more transportable) and cheaper. An Iron Dome battery runs around $50 to $100 million, while a single PATRIOT battery comes in at over $1 billion.

Second, a single PATRIOT PAC3 missile is roughly $4 million per shot, while an Israeli Tamir missile costs only $50k. The Tamir is more appropriate for the types of threats the MLR is likely to face as a mobile, highly dispersed force. China is unlikely to launch high volumes of ballistic missiles at the MLR, but drones, smaller missiles, rockets, artillery, and mortars can be expected.

Third, the Iron Dome software is just as important for what it doesn’t do. Friendly force locations can be mapped into the Iron Dome, and if it calculates that an incoming munition won’t threaten friendlies, the Iron Dome does not fire. Not firing is absolutely critical while operating under the threat of precision guided munitions, since the firing signature is likely to be identified by enemy sensors.

Since the Iron Dome was developed for use over heavily populated cities, the software can even calculate the rough likelihood that debris falling from an interception would land on friendlies. Iron Dome avoids this when possible, furthering force protection.

Fourth, all of these capabilities add up to reduced logistics requirements for the MLR, which will be helpful for the overtasked combat logistics battalion. A smaller and more affordable system which is frugal with ammo will go a long way towards easing resupply tonnages.

Fifth, the MRIC will likely be C-130 transportable. This is critical for Marine forces which organically operate the KC-130J within the Marine Air Wings (MAWs). C-130 cargo aircraft are able to operate from shorter runways than the Air Force’s C-17 heavy lift cargo aircraft, giving the MLR more operational flexibility. The PATRIOT system is only air transportable by C-17.

The LAAB will also almost certainly employ some type of supplementary radar system such as the Light Marine Air Defense Integrated System (LMADIS) in order to enhance air detection against slower moving aerial targets like drones and helicopters. The system is extremely light, well-suited for the footprint of the MLR.

Combat Logistics Battalion (CLB)

The CLB of the MLR will have an extremely challenging mission. The ability to sustain numerous, austere, platoon-sized sites spread across multiple islands while under the threat of enemy precision guided munitions is something the US does not have experience executing.

Combat Logistics Battalion vehicle loading an ISO container

The CLB will need to operationally juggle multiple issues simultaneously:

Sufficient delivery of bulky missiles including at a minimum the NMESIS, MRIC (Tamir), and Stinger munitions.

Maintenance, parts replacement, and hot-swapping of extremely sophisticated radars (the MLR will have at least the LMADIS and the G/ATOR radars associated with the MRIC).

Management in the air domain: the CLB will be required to create expeditionary forward arming and refueling points (FARPs) to land C-130 cargo aircraft with short take-off/landing capability, F-35B fighters with vertical take-off/landing capability, and any number of rotary wing assets (helicopters). This is a small nightmare, with numerous requirements like the identification of suitable sites, clearance of foreign object debris (FOD), providing security, upload/download of data to/from airframes, massive aviation fuel requirements, and any engineering required to modify the landing site.

Supplying the MLR will require caching of supplies both preplanned and during operations. The tracking of cache supplies has historically been difficult to execute. Tracking what each cache contains and where it is located is more difficult than it sounds.

The CLB will require tight coordination with adjacent Navy, Army, Air Force, and Special Forces logistics units. In a sense, the MLR CLB is not a traditional high-capability logistics unit, but more of a hustling logistics middleman attempting to match expenditures with inputs just-in-time on the fly. A mistake by the CLB would leave the entire MLR dangerously exposed and highly vulnerable to the enemy.

Management in the sea domain: the CLB will be required to employ or work alongside a fleet of sea vessels to move forces and supplies around the theater. Ship loading and unloading plans are complex tasks affected by weather, sea state, steam times, enemy action, underwater hydrography, and a host of other variables.

The charging, replacement, and management of batteries. Depending on the optics, drones, radios, and other equipment employed by the MLR, this could be a massive headache.

Just supplying the MLR’s water needs could be an enormous challenge to the CLB. The Corps should seriously consider sending its best logistics Marines to serve in the MLR CLB while perhaps doing logistics cross-training with Special Operations Command (SOCOM) logistics units. Logistics integration and the placement of MLR CLB liaison officers alongside Navy Expeditionary Logistics Support Groups (NAVELSG) and Army Watercraft Systems units would be prudent.

Dedicated Enablers

There are a few platforms assigned to the MLR that likely do not belong exclusively to the regiment. An unknown number of MQ-9A Reaper unmanned aircraft will fly in support of the MLR. The Reaper is a highly capable and battle-proven hunter-killer drone. They are obviously remotely piloted, and in this case likely from the continental United States. The Reaper will give the MLR the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities to find targets for the NMESIS and whatever joint shooters are available.

The MLR will require organic sealift, with the original plan relying on the US Navy building 35 Light Amphibious Warships (LAWs). The LAW acquisition program has experienced some turbulence, undergoing a redesignation to the Landing Ship Medium (LSM) as the US Navy and USMC possibly agreed that the new requirement is between 18 to 35 vessels. The LSMs will be critical to the movement of the future MLR. This is a watershed moment for the Navy Marine Corps team, since essentially an entire second amphibious fleet is under consideration. The MLR will be supported by a fleet of LSMs with a few Landing Platform Dock (LPD) vessels, while Marine regiments task organized into traditional Marine Air Ground Task Forces (MAGTFs) will retain the Landing Helicopter Assault (LHA) large deck amphibious assault ships with the bulk of LPDs in support of the LHA core. Recently, the USMC has stated that each MLR will require 9 LSM vessels.

History of the Concept

At the turn of the last century, the United States found itself in need of military power projection capabilities. Rising empires like Germany and Japan, not to mention established ones like Great Britain, were maintaining and developing naval capabilities able to threaten US interests globally. The Spanish-American War (1898) left the US with difficult to defend territories flung far across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The Navy Department turned to the US Navy and US Marine Corps to develop a rapidly deployable expeditionary force able to wage maritime warfare on a much quicker timeline than mobilizing the US Army through the Department of War.

In order to man these new expeditionary formations, the USMC was forced to make the controversial decision to divest itself of the Navy ships’ guard mission. Marines had traditionally acted as shipboard security and military police, guarding US Naval officers against the mutiny of their enlisted sailor crew. In fact, even after the decision was made to focus on amphibious operations vice ship’s guard, Naval officers (when outranking their Marine counterparts) would sometimes issue orders for Marines to return to ships’ guard duties. This even occurred at the 1903 Advanced Base Force exercises in Culebra, Puerto Rico. During the training schedule, the Captain of the USS Panther ordered a portion of the Marines to return to ships’ guard, seriously impacting the value of the exercises.

There were also challenges from within. The East Coast Marine Corps in particular did not embrace the advanced base force concept. Between the end of the Spanish-American War (1898) but before the beginning of the Good Neighbor Policy (1934), Marines operating in the Atlantic region were deeply involved in counterinsurgency operations spanning Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic. In addition to these operations, East Coast Marines were required to maintain two large forward deployments in both Panama and Cuba. The hard-won experiences from this time period coalesced into the USMC Small Wars Manual, published in 1940. The manual remains a classic in counterinsurgency doctrine. However, small wars lessons learned would be entirely insufficient for the gathering storm across the Pacific.

Despite these difficulties, the Marine Corps developed the Advanced Base Concept centered around two amphibious units. The Fixed Defense Regiment focused mainly on, unsurprisingly, defense. The Mobile Defense Regiment, confusingly, was designed with offense in mind.

In 1914, the Mobile Defense Regiment (the first of its type commanded by John A. Lejeune) consisted of:

Headquarters Company

4x Rifle Companies

1x Machine Gun Company

1x Field Gun Battery

In 1915, the Fixed Defense Regiment consisted of:

Headquarters company

C Company, trained to conduct harbor defensive mining.

E Company, trained in radio, telephone, telegraph, buzzers, and visual signaling.

F & I Companies, responsible for fixed batteries mounted in harbor defense.

H Company, trained both as a combat engineer company and as a heavy automatic weapons company.

1x Field Artillery Battery which manned 3-inch (76 mm) field pieces

1x Aviation Company with 10 officers and 40 Marines (organized by Alfred A. Cunnigham).

The USMC termed these forces, when combined, the Advanced Base Force (the future Fleet Marine Force). The echoes of the Fixed Defense Regiment can be identified in the modern Marine Littoral Regiment. Both have a separate communications company to ensure dispersed units can share information. Both are heavy on fires based assets able to target both sea and air platforms. Both have an aviation element for reconnaissance and strike. Perhaps the modern MLR would do well to research the employment of advanced sea mines.

For the next twenty years, the USMC would exercise, test, learn, innovate, and iterate over and over again in developing the expeditionary force that would eventually fight and win in WWII. Development of the concept was punctuated by the participation of the 2nd Advanced Base Force in the amphibious landing against Vera Cruz, Mexico, and temporarily stalled in 1917 by American entry into WWI (with Marines making up half of the US Army’s 2nd Division in a land-oriented European war).

Of crucial importance to keeping the Advanced Base Force concept alive was the work of two visionary Marine intelligence officers (Dion Williams and Earl H. Ellis), who added invaluable depth and real-world context. Williams and Ellis were able to carry the effort forward to its eventual final evolution into the Marine Defense Battalion (formerly the Fixed Defense Regiment) and Marine Battalion Landing Team (formerly the Mobile Defense Regiment).

While the exploits of Marine Battalion Landing Teams and amphibious assault units during WWII are well known, the record of the Marine Defense Battalions (MDBs) are forgotten. Since the MDB is the historic predecessor of the MLR, we will discuss it in some detail here.

In 1939 the Marine Defense Battalion (MDB) consisted of:

HQ Company

Service Battery (6x Platoons each with searchlights and aircraft sound locators)

Coast Defense Group (3x Batteries, each with 2x 5” Mk 15 guns)

Anti-Aircraft Group (4x AAA Batteries, each w/ 4x mobile 3” M3 guns)

2x AAA Companies, each w/ 24x M2 .50-cal machine guns on AA mounts

2x Beach Protection Companies, each w/ 24x M1917A1 water-cooled .30-cal machine guns

Unit insignia of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion

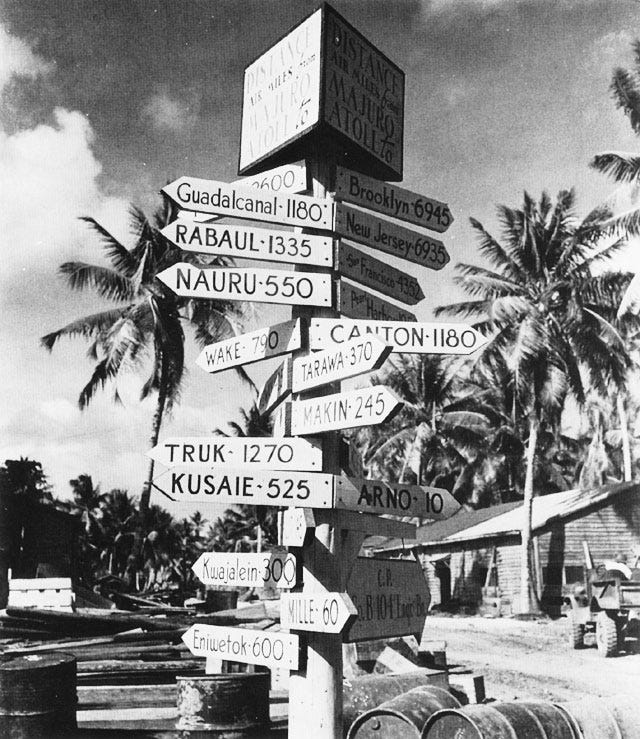

The Corps would eventually field twenty of these MDBs throughout WWII. The first operational contact for an MDB occurred at Wake Island, as the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor and Wake simultaneously (7 Dec in Hawaii, 8 Dec in Wake due to the international dateline). The 1st Marine Defense Battalion delayed the Japanese occupation of Wake for 13 to 15 days, knocking out 1 submarine, 2 Patrol Boats, 2 Destroyers, and 10 aircraft. The Marines killed roughly 400 enemy in exchange for 12 US aircraft and 52 KIA. 1st MDB also defeated the Japanese force’s first landing attempt. Not a bad result considering Japan conducted a surprise attack and then isolated 1st MDB from resupply. This would be the only defeat of an MDB during WWII.

In June of 1942, 6th Marine Defense Battalion on Midway Atoll fought off multiple waves of Japanese air attacks, contributing to the tide turning victory at the Battle of Midway. The commander of Battery H, 6th MDB, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor during this action through one of the shortest citations ever written:

“For distinguished conduct in the line of his profession, extraordinary courage and disregard of his own condition during the bombardment of Sand Island, Midway Islands, by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. 1st Lt. Cannon, Battery Commander of Battery H, 6th Defense Battalion, Fleet Marine Force, U.S. Marine Corps, was at his command post when he was mortally wounded by enemy shellfire. He refused to be evacuated from his post until after his men who had been wounded by the same shell were evacuated, and directed the reorganization of his command post until forcibly removed. As a result of his utter disregard of his own condition he died from loss of blood.”

By August, 3rd Defense Battalion would land on Guadalcanal, defending the island and port against Japanese counterattacks. In particular, 3rd MDB knocked out three enemy landing ships disgorging Japanese infantry in an amphibious counterattack. 3rd also defended Henderson Field, the site of a legendary battle which contributed to 1st Marine Division’s victory on Guadalcanal. 9th MDB would share the burden of this victory by destroying a dozen enemy aircraft attempting to attack Koli Point airfield.

In 1943, the 9th, 10th, and 11th Defense Battalions crossed interservice lines to support the US Army XIV Corps’ attack through the rest of the Solomon Islands chain. By 1944, Marine defenders participated in the assault on the Marshall Islands, including Guam and Saipan. As the US gained the initiative in the Pacific, operations naturally required less port/beach defense units. The number of MDBs was cut from 20 to 18, and 15 of the remaining MDBs were converted into purely anti-aircraft units. These late war Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalions (AAA Bn) were equipped to fire high volume sheets of steel upwards, covering ground units’ offensive maneuvers.

Walt Disney supposedly designed the 17th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion’s Insignia. The AAA Bns were the Defense Battalion’s successor.

For the assault on Okinawa, 2nd, 5th, 8th, 10th, and 16th AAA Bns consolidated into the 1st Provisional Anti-Aircraft Artillery Group (1st PAAG). As Marine and Army landing forces of the first wave captured Yontan Airfield (the first airbase utilized by the US on Okinawa), 1st PAAG executed a rapid landing to defend their fellow warfighters and the airfield. Once in position, 1st immediately integrated into the naval/air defense zone.

5th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion (Formerly 5th Defense Battalion) throws a wall of tracers and steel upwards to intercept a Japanese Air Raid over Okinawa. Marine Corsairs are parked in the foreground. Department of Defense photo (USMC) 08087 by TSgt C.V. Corkran

Simultaneously, the Imperial Japanese Army was planning a special operation. Five Mitsubishi Ki-21 Heavy bombers carrying commando squads were committed to destroying Yontan and the recently captured Kadena airfields. 1st PAAG was ready, destroying the heart of the raid force by downing four of five Ki-21s.

The fifth Ki-21 landed in a belly slide onto Yontan airfield, with 12 Japanese commandos emerging from the wreckage. This small group was able to destroy 38 US aircraft and 70,000 gallons of fuel. The destruction of the other 4 bombers kept US damage to a minimum, with Yontan reopening at 0800 the next day. By the end of the Battle of Okinawa, 1st PAAG was credited with downing more than 30 Japanese aircraft of all types.

Department of Defense photo (USN)

When fighting in Europe or the Middle East, the Marine Corps has the luxury of integrating with the US Army for logistics as well as heavy air defense and fires assets. This is quite different from fighting in Asia, where the Corps has historically required agile maritime fires-focused units able to act as the jab, protecting and creating operational space for the amphibious assault forces’ counterhook.

Taken in the proper context of WWII, the MLR is neither revolutionary nor evolutionary. It is simply a modern update to the Marine Defense Battalion, which was an update to the Fixed Defense Regiment. The concept is over 105 years old; light on personnel and heavy on fires, purpose built for naval/littoral warfare, the Marine Corps needs a MLR today and it will need a MLR in the war after the next war.

How does the modern MLR Fit Into the National Defense Strategy (NDS)?

The MLR concept likely developed independently from the 2018 National Defense Strategy, but they are mutually supporting. The 2018 NDS established a Global Operating Model comprising four layers: contact, blunt, surge, and homeland.

The Marine Corps’ MLR operates as a contact unit which also supports the blunting force. Contact forces (the USMC terms contact forces within the range of persistent enemy precision networks “inside forces”) are meant to operate far forward of the bulk of US troops in order to provide deterrence, intelligence, and a routine competition force. In terms of the first mission, contact troops are meant to deter small enemy fait accompli attacks. These are short and sharp military operations designed to take a small piece of territory and then de-escalate, avoiding a larger conflict.

As for the second mission, contact units give the combatant commander boots on the ground, eyes on, and a forward posture enabled to send current information and intelligence up to HQ and the other layers (blunting, surge, and homeland).

The third mission involves day-to-day competition with US adversaries. Contact units train, operate, and live in areas where operations are on-going or expected to occur. These units work hand-in-hand with US allies and partners to resist and contain adversary gray zone and competition activities below the threshold of war.

Contact units are typically smaller and lighter while easily able to disperse in order to avoid enemy detection. Examples of contact forces include US Army Special Operations teams, US Army Security Force Assistance Brigades, Marine Littoral Regiments, and forward deployed naval task groups.

Blunting forces are the rapid-reaction forces in readiness postured to deter and if necessary prevail against enemies of the US in combat. The mission of the blunting force is to deny enemy military objectives long enough for the surge and homeland forces to deliver the decisive victorious blow.

These units are generally based either in Allied countries or on US soil, not as far forward as the contact layer.

The MLR plays an enabling role for the blunting and surge forces. The MLR’s ability to sense forward of most friendly units as well as conduct strikes against high value targets means these Marines are able to:

Deliver critical time sensitive information on enemy disposition to US operational commanders preparing the counterattack. (Support Maritime Domain Awareness, Support Operations in the Information Environment)

Attack enemy high value targets in order to either create gaps for friendly counterattackers or confuse the enemy as to the direction of the main effort. (Conduct Strike, Conduct Surface Warfare)

Support strikes against critical nodes to disrupt/slow down enemy operational tempo in order to deliver more decision space for blue commanders. (Conduct Strike, Conduct Surface Warfare)

Integrate into a more mature joint air and missile defense zone in order to protect massing friendly forces. (Conduct Air & Missile Defense)

Public Criticisms of the Concept

A portion of the Marine Corps’ retired and active leaders have been unusually vocal about criticizing the MLR concept in public. There are many criticisms. The first is that Force Design 2030 (the parent construct of the Marine Littoral Regiment) focuses too narrowly on China and the Pacific. In Vermilion’s assessment, this criticism can be thrown out almost immediately. The Department of Defense has made it clear that China will be the pacing threat for the US military writ large for years, even post-Ukraine invasion. This means the long term priority effort is in USINDOPACOM. Due to the large expanse of ocean in the Pacific and the theater’s naval nature, the Marine Corps has found itself drawn to Asia time and time again (Zeilin’s mission to Japan, the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Uprising, the 14 year mission to Shanghai, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, and today’s forward posture). The Marine Corps has had much less of an impact historically in Europe/EUCOM. This leaves the Middle East as the last major theater, something that would be a head scratcher to make the Marine Corps’ primary focus.

The second criticism is that the MLR hollows out the Corps’ combined arms force. This is again hard to believe. The first two MLR were raised at the cost of two infantry battalions and two artillery battalions, hardly major investments. The main driving force behind the reduction of Marine infantry forces is not Force Design 2030, but a relatively low defense budget. This is a Congressional driven pressure, not one imposed internally by Marine Corps leadership. The Marine Corps was only able to maintain 27 infantry battalions during twenty years of fighting two simultaneous land wars by the support of the temporary overseas contingency operations (OCO) fund.

The hollowed out criticism hits harder in discussions surrounding scaling down the infantry battalion’s end strength. However, Marine Corps leadership believes there are many reasons to create smaller infantry battalions, which is a discussion for a different article.

The third criticism is that Force Design 2030 and the MLR concept have not gone through the rigorous combat development (joint capabilities integration development system [JCIDS]) process. While this allegation is difficult to ascertain, it certainly seems that the Force Design 2030 process has gone through the typical large number of institutional checks (as can be seen in the graph below). Additionally, Commandant Berger, before assuming the responsibilities of the office of the Commandant, served as not only the Commanding General of Marine Corps Combat Development Command, but also the Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration. Both of these positions are directly responsible for the combat development process and respond directly to the Commandant.

Traditional activities that supported/will support the development of Force Design 2030

A fourth criticism is that Force Design 2030 will harm the culture and ethos of the Corps. This is not directly related to the MLR and will not be addressed in this article. However, it can be said that the Marine Defense Battalions of WWII certainly did not harm the ethos of Marines in the ‘40s. On the contrary, the story of the 1st MDB’s actions at Wake Island are an integral part of Marine Corps lore.

General Paul Van Riper (USMC Ret) has also leveled a number of criticisms. Many of these arguments are over the degree to which the main effort of the Marine Corps is shifting to the MLR. Yet there is no force design effort to field more MLRs than traditional Marine regiments, nor is there any doctrinal shift to a defensive orientation. In fact, the MLR is meant to complement and facilitate the offensive actions of the MAGTF against a peer adversary. As exists, the MAGTF currently has no robust organic air defense capability. This would have to change under any future construct, whether Force Design 2030 or not. By resisting the introduction of missile units, this collection of officers is simply fighting modernity.

In particular, Van Riper’s criticism of upgrading cannon artillery to missile firing High-Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARs) seems particularly short-sighted after the experience of the Ukraine War.

Another clarion call for criticism of the MLR has been a critique of 1st Marine Defense Battalion’s record during the Battle of Wake Island in WWII. As reviewed above, 1st MDB was isolated, surprise attacked, and prevented from resupplying. Even under these conditions, 1st MDB inflicted roughly eight times the number of casualties on Japanese forces and significantly delayed Imperial Japanese Navy operations at low cost. This is the mission of a modern contact force. Critics point to 1st MDB’s failures as inherent to the concept, but ignore all the subsequent MDB successes through WWII.

Supporters of Force Design 2030 recognize this inherent vulnerability. Col Michael Kennedy USMC (Ret), writing for the Marine Corps Association: “The MLR’s purpose will be to observe and prevent any “gray zone” activities that lead to fait accompli actions. In some cases, it is presumed that they may be the “trigger” that shifts the status from competition to conflict if any premature hostile acts are directed towards their positions.” [emphasized text added by author]. The Marine Corps knows the MLRs during peacetime will operate far forward, vulnerable to enemy first strike surprise attacks. The information gleaned from these forward deployments is more likely to prevent strategic surprise today, and the Commandant is accepting risk in his force posture.

There are some criticisms that are more valuable, though they pertain to the MAGTF and not the MLR. Turning again to Van Riper, the Marine Corps made the decision to divest itself of main battle tanks in order to fund modernization requirements. System agnostic, the value of mobile protected firepower has been a consistent battlefield requirement since WWI. Van Riper is likely correct in pointing out that totally removing the USMC armored force leaves a critical battlefield gap, and one the US Army is unlikely to fill rapidly in wartime.

Infantry battalion thickness is another point Van Riper hits home on. The Marine Corps is scaling down the size of infantry battalions while preparing for war with a peer adversary. Under these circumstances, casualties will be high, so it seems more realistic to increase the end-strength of the infantry battalion.

Finally, the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) discussed limitations of the MLR concept in their recent unclassified wargame. CSIS assumed the MLR would still be equipped with the relatively short-ranged NMESIS and that no forward prepositioned supply of missiles were available. These are both critical weaknesses that will almost certainly be addressed with time. Take it from the Assistant Commandant:

“I’m pretty confident on the Naval Strike Missile, and that we will get range – we’ll always want more range, but we will get range off of that. And then again, I build a unit that can employ long-range fires against adversary targets that can move, which includes ships. So if a newer, better system comes along in seven, eight, nine years, five years, we can shoot that too; I’m agnostic about what I shoot.”

- General Eric M. Smith, Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps (Then Lieutenant General, Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration)

Evaluation of the MLR Concept - What Can Be Done Better?

1. In rolling out Force Design 2030, Marine Corps leadership needs to better publicize the roadmap of the future MAGTF GCE. Marine infantry is not being de-emphasized. The exact opposite is happening with the ongoing infantry battalion redesign, the organic precision fires (OPF) concept, and upgrades to missile systems. The future infantry battalion will fight with a shield of loitering air drone munitions forward of the front line, conducting persistent precision strike against enemy units to the battalion’s front.

2. The limitation on NMESIS is clear, since the Naval Strike Missile (NSM) lacks the range to engage targets past 200 to 250km. Further development of Kongsberg’s NSM could yield improved range. 500km is roughly the minimum desired range capability. Increasing the missile’s speed to hypersonic would greatly increase its chance of avoiding interception. The USMC should also be thinking about whether the MLRs need the M142 HIMARS, since the Corps already operates that platform. The US Army will continue to develop sophisticated HIMARS missiles the Corps can purchase without paying for research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E) costs.

3. In order for the MLR to function as necessary during wartime, significant forward supply caching operations must commence immediately. Once the design of the MLR is fixed and the systems are known, USMC logistics units must begin the construction of dispersed caching sites containing ammunition, food, water, and fuel. MLR units’ effectiveness severely decreases without the ability to reload (as demonstrated during the CSIS wargame). 1st MDB’s surrender at wake was due almost certainly to a lack of supply.

4. The US Navy and US Marine Corps must agree on and field an effective means to move the MLR rapidly while avoiding detection. This has simply not happened yet, and is a glaring flaw for execution of the concept. Congressional, Secretary of Defense, or even potentially Presidential attention may be required to force the services to embrace a viable solution. This same strategic political pressure may also be required to deconflict and create means for the MLR and US Army Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) to provide mutual support. The MDTF uses different equipment with different capabilities from the MLR, but the concept is very similar.

5. During WWII, the Defense battalions lacked infantry, so it is good to see this deficiency corrected since the MLR’s LCT is built around an infantry battalion. This gives the MLR more staying power and protection against enemy amphibious assaults/landings. However, the MLR is unlikely to hold against determined and sustained attack by land forces. Marine Corps Leadership must start articulating how the MLR and the traditional MAGTF concepts mutually support one another.

6. Increase communication to Marines and sailors . Many service members question the reasoning behind certain changes made under Force Design 2030 and the MLR structure. Marine Corps leadership should be more deliberate about communicating the why behind changes to the force.